Time, distance and prison walls haven’t stopped Ortralla Mosley’s killer from reaching out

Editor’s note: This article describes abusive dating relationships and the violent murder of a high school student. Call the National Teen Dating Abuse Helpline at 866-331-9474, text “LOVEIS” to 22522 or visit loveisrespect.org for immediate, confidential assistance.

The thick prison walls and spools of razor wire more than 200 miles away should have put RaeAnne Jones at ease. Marcus McTear can’t get anywhere near her.

But he hasn’t forgotten about her. In fact, she was easy to find, right there on Facebook. Even from the maximum security prison where McTear is serving time for murder, he found ways, with the help of others, to contact the ex-girlfriend he abused when they were freshmen in high school.

“Every time there’s a message request or something that comes up on Facebook, it’s like a trigger because I’m like, ‘Oh, my gosh, is this him again?’” Jones, 35, told me from her home in a small Texas town, where she’s now married and raising two kids.

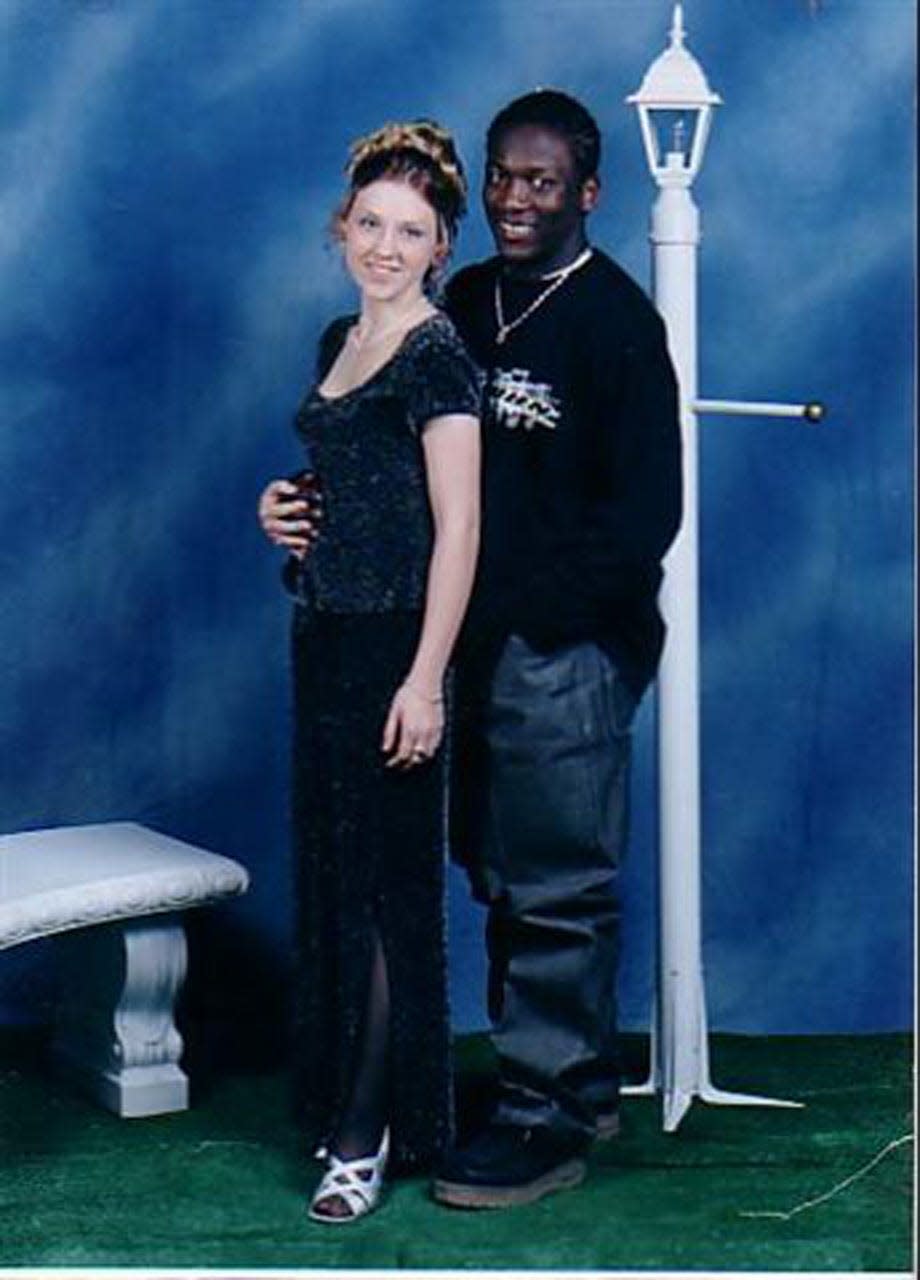

Longtime Austinites might remember Jones under her maiden name: RaeAnne Spence. Two decades ago, she was the teenager who dated McTear before he dated Ortralla Mosley, the 15-year-old whom McTear stabbed to death in an upstairs hallway of Reagan High School on March 28, 2003.

Jones’ story is both prequel and epilogue to Ortralla’s murder. Jones’ complaints of violence a year earlier raised bright red flags about McTear that school administrators failed to take seriously, prompting her family to move across town for safety. After the tragedy, Jones’ advocacy contributed to greater awareness about teen dating violence, including the creation of toolkits to help other teens.

But in this moment, Jones is a survivor worried about the future. McTear, now 36 and reaching the halfway mark of his 40-year sentence, is being considered for parole.

“If he's already tried to contact me in prison, how's he going to be if he's out, when he has the freedom to do so?” Jones said. “He's going to have a phone. He's going to have access to social media. My whole life, as I know it, has to change again if he's released.”

‘Do you want his address?’

From the confines of a Texas prison, an inmate can send a letter or make a phone call to anyone — unless that person has told the prison system they don’t want contact from that inmate. Even then, nothing stops a cellmate or a friend from serving as an intermediary.

That’s what happened with Jones. On two occasions, she said, men recently paroled from the Memorial Unit — McTear’s prison in Rosharon, south of Houston — reached out to her on Facebook and encouraged her to contact McTear.

Both times she told them: Not interested.

She said she also reported the unwanted contact to the state prison system.

Then last April, Jones received a detailed Facebook message from someone claiming to be a counselor named Jeremy.

"I was at a counseling session and saw someone you know doing good and living a positive life,” the message began. “He has come a long way and looking to do some big things musically. He has talked about you(,) wanting to reconcile and make amends(;) he has a positive and open mind frame. A lot more mature. Been through too much. Know who I am talking about? Marcus. He has grown. Do you want his address?”

Before Jones could respond, “Jeremy” sent a second message with McTear’s prison address. “Step out on faith and see what comes,” he wrote.

For the record: Counselors don’t do this kind of thing. They don’t look up a person you talked about in therapy and message them on Facebook.

Jones also noticed a difference in tone from the two parolees who previously messaged her. “Jeremy” went on to invoke God’s forgiveness in ways that felt manipulative to Jones, who is religious.

And then there’s the fact that “Jeremy,” claiming his own phone was out for repair, made contact using a Facebook account belonging to someone with a totally different name — a name shared by an inmate at the same prison as McTear.

That inmate is serving a 60-year sentence for aggravated robbery, aggravated assault and arson for a 2012 drug-fueled crime spree near Houston. His mug shot from that arrest shows tattoos that are also visible in more recent selfies posted on the Facebook page.

Not talking now

As a rule, inmates in Texas prisons don’t have access to the internet. It’s far more likely a person outside the prison would be behind any Facebook account, said Texas Department of Criminal Justice spokesman Robert Hurst.

I asked whether it’s possible an inmate had a smuggled cellphone, a well-documented phenomenon in other prisons.

“That's always a possibility,” Hurst said. “But we're pretty good about finding that kind of stuff.”

He couldn’t comment on incidents involving specific inmates, including whether McTear had been disciplined for efforts to contact Jones. State law says most information about inmates is confidential, apart from their name, conviction, prison and expected date of release.

Whoever’s behind the Facebook account used by "Jeremy" hasn’t posted since Jan. 8 and didn’t respond to my inquiries.

I sent McTear a couple of letters in prison, asking about these attempts to contact Jones and other aspects of his life over the past 20 years. He said he was interested in talking but had “diligently been counseled” to speak another time about the events surrounding Ortralla’s death and his incarceration.

“My willingness to shed light on the sensitivity and high importance of this tragic situation has not ceased,” McTear wrote, “but as (a) believer the Bible speaks of times and appointments."

Even if a person is reaching out to express remorse, it's a problem to repeatedly contact someone who doesn't want to hear it.

“That kind of boundary violation is an important thing to pay attention to,” said Anne DePrince, a professor at the University of Denver who studies the impact of violence and trauma on women and children. “It can be a sign of somebody trying to exert power and control.”

Read more

Ortralla Mosley’s mother sought help for her daughter’s killer. She’s done trying.

Sharing Ortralla Mosley’s story turned teacher’s grief toward helping others

Signs of trouble

Indeed, those were defining themes when Jones dated McTear during their eighth and ninth grade years. Jones said it started small: McTear telling her not to wear makeup, shorts or crop tops. Then he told her not to talk to other boys. New to dating, Jones figured this must be normal.

“I was kind of isolated to where he was my only friend,” she said. “And that happened pretty quickly.”

Jones’ mother, Elaine Naivar, grew alarmed. She met with McTear’s parents. She said they agreed the teens should stay apart.

“That didn’t work out, because he would still follow her,” Naivar recently told me.

McTear’s parents, Joseph and Dorothy McTear, did not return my calls about this case.

As a teenager, Jones initially defied her mother’s wishes and kept seeing Marcus McTear. After a while, though, she didn’t want to risk getting in trouble, and she started to think a break would be good for them both.

“Just the term ‘breakup’ was traumatic to him, and that's when he showed me a totally different side of who he was,” Jones told me. “That's where he began to get physically abusive to me.”

It started with yanking on her backpack while she was still wearing it. Then biting her on the face and hitting her in the back.

Then one day he pushed her down the stairs at Reagan High School (now known as Northeast High School).

Jones called her mother, and they sat down with school administrators. Jones said the school officials didn’t believe her.

They asked her: “Why haven't you told us before (that) this stuff’s been happening? Are you just mad because he's breaking up with you?”

Actually, she was the one breaking up with McTear, a popular student on the football team.

“And I realized, ‘Oh, my gosh, I don’t have support here,’” Jones said.

Then in January 2002 — 14 months before Ortralla was killed — McTear turned to Jones in the middle of theater class and whacked her three times on the side of her head with his binder. Jones was dazed, her ear ringing, her body filling with rage.

“I just got up and I hit him back as hard as I could,” she said.

Both teens were suspended for three days, according to records later filed as part of Jones’ family’s lawsuit against the Austin school district. (The district eventually settled the suit for $45,000.)

Worried about leaving her daughter at home — in the same Northeast Austin neighborhood where McTear lived — Naivar brought Jones with her to work.

Then Naivar got a call from the front office of her son’s elementary school. A young man matching McTear’s description but claiming to be the third grader’s stepfather had tried to sign the child out. The school sent the impostor away.

Nothing came of Naivar's complaints to Austin school district police. She managed to get the Austin Police Department to file charges after McTear pushed Jones down in a school bus. A judge tossed the case a few months later.

When the summer came, Naivar moved her family across town to a new home and new schools. She told her 15-year-old daughter: Don’t tell any of your friends where we’re going.

Keeping the community safe

The next March, Jones watched with horror as television news crews broadcast the story of Ortralla’s murder on her old campus.

"You feel terrible for her and her mom — just seeing her mom on TV," Jones said. "And then there's that little voice in the back of your mind that, all right, it could've been me. Like, literally ... I escaped this."

The girls hadn’t been close. But Jones has this memory of Ortralla, this look of compassion and concern that Ortralla shot her one day in their freshman year, as Jones was crying in the hallway after an argument with McTear.

“It's like she wanted to say, ‘Are you OK?’” Jones told me. “I just remember feeling like, in that moment, that she cared.”

After the murder, it was Jones’ turn to speak out. She shared her story at teen dating violence awareness events and was featured in a broadcast of the news program “20/20.” She joined up with the American Bar Association and other youths to create educational resources for their peers. In 2006, Congress declared the first national teen dating violence awareness week. In 2010, it grew into the full month of February.

Here in Texas, a 2007 law required public schools to develop policies for addressing dating violence.

Yet the progress has been uneven. Two years ago, Gov. Greg Abbott vetoed another law that would have required schools to teach middle and high students about preventing dating violence, family violence and child abuse. He later signed a revamped version that says parents must opt in for their children to receive this vital information.

Abbott cited his ongoing mantra about parents’ rights. But this safety information shouldn’t be any more controversial than first aid or fire drills.

“The data are really encouraging that if we can get these kinds of (dating violence prevention) programs to young people, they can make a difference in changing young people's views of relationships” and helping them resolve conflicts without aggression, said DePrince, the professor at the University of Denver.

The implications go beyond that. People with a history of domestic violence, or people who set out to kill a family member or an intimate partner, were responsible for two-thirds of the mass shootings between 2014 and 2019, making the earlier signs of abuse particularly crucial to address.

Dating violence “is not just a problem for survivors and abusers,” DePrince said. “It affects our overall safety as a community.”

Dating abuse is a pattern of coercive, intimidating, or manipulative behaviors used to exert power and control over a partner. Such behaviors by an abusive person may include:

• Checking your phone, email or social media accounts without your permission

• Putting you down frequently, especially in front of others

• Isolating you from friends or family — physically, financially or emotionally

• Extreme jealousy or insecurity

• Explosive outbursts, temper or mood swings

• Any form of physical harm

• Possessiveness or controlling behavior

• Pressuring or forcing you to have sex

For support, call the National Teen Dating Abuse Helpline at 1-866-331-9474, text “LOVEIS” to 22522 or visit loveisrespect.org.

SAFE offers Expect Respect support groups in some middle and high schools to help young people who have been exposed to violence in the community, at home or in peer relationships. All services are free, confidential and provided at school during the day. To learn more, or to talk to someone about teen dating violence, email expectrespect@safeaustin.org or contact the 24-hour SAFEline at 512-267-7233; text 737-888-7233; or chat at safeaustin.org/chat.

Source: Love is Respect, a project of the National Domestic Violence Hotline

Forgiven but not reconciled

Jones doesn’t want to talk to McTear. But she has forgiven him. Holding onto her pain and anger wasn’t doing her any good.

She is troubled, though, by the word “Jeremy” used: reconcile. As in rebuilding a relationship, getting back into each other's lives.

Jones wants no part of that. "I have to protect me and mine now,” said Jones, who believes McTear should serve his full 40-year sentence for taking Ortralla's life.

Back when they were teenagers living in the same neighborhood, ordered by their parents to stay apart, McTear came over anyway. He walked in circles around the cul-de-sac by Jones' house, at once moving and going nowhere.

If McTear is paroled early, Jones doesn’t know whether he would show up again outside her home.

But she can’t rule it out.

Grumet is the Statesman’s Metro columnist. Her column, ATX in Context, contains her opinions. Share yours via email at bgrumet@statesman.com or via Twitter at @bgrumet. Find her previous work at statesman.com/news/columns.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: In prison for Ortralla Mosley's murder, Marcus McTear reaches out