In a time before PA systems, rodeos used a guy with a loud voice. His name was Fog Horn

Think back to a time before public address systems. You have an event that needs an announcer – an auction, sporting event, or rodeo. What you need is someone with a very loud voice – loud enough to carry throughout the venue so that everyone can follow the action.

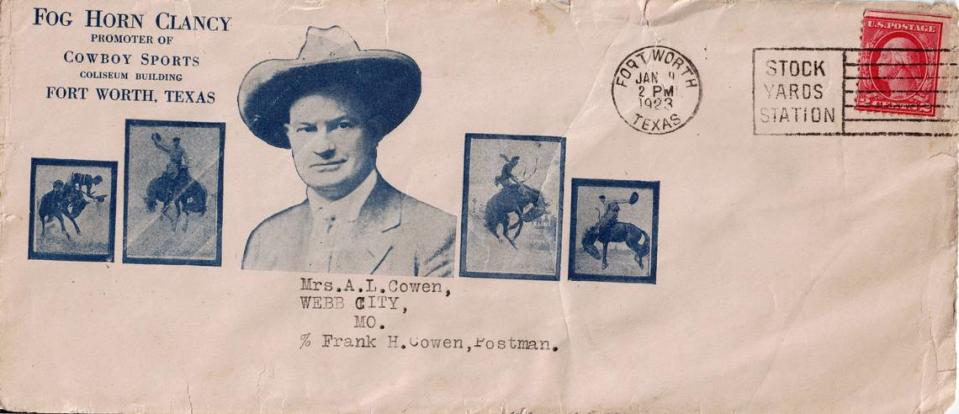

You need Frederick M. Clancy, otherwise known throughout Texas and the country as “Fog Horn” Clancy.

Born in 1882, Clancy got his start as a ranch hand just outside Mineral Wells when he was about 14. After two years, he tried to join the Army, but wasn’t old enough. As Clancy tells it, he sold the local Mineral Wells newspaper on the street – which was when people first started to call him “Fog Horn” because of his booming voice. (His name was sometimes spelled Foghorn, but Clancy seemed to prefer Fog Horn. It only took a few years for Frederick, his given first name, to disappear from newspaper stories. He was even listed in the 1920 U. S. Census as “Fog Horn Clancy.”)

In July 1898, Clancy and a friend went to San Angelo for the Fourth of July celebration. There he entered a bronc riding contest, but was promptly bucked off – suggesting that other lines of work might be a better fit. Fortunately, the show’s promoter had heard about his work for the newspaper in Mineral Wells and offered Clancy a job as an announcer.

It wasn’t a full-time gig, so Fog Horn also sold mineral water for health purposes, town lots in the Oklahoma Territory and, in 1905, became the business manager and announcer for Samwells Dog and Pony Circus out of Chickasaw. It didn’t take long for the story of Clancy’s booming voice to travel.

One commenter said that Clancy’s voice, “sounded like a foghorn at sea,” while another claimed that his voice could be heard in Mexico when Clancy and the cowboys gathered in Waco.

In 1911, Fog Horn secured a contract to announce events at the Oklahoma State Fair in Tulsa. Many rodeo announcing jobs followed as the sport developed. Clancy also regularly announced at boxing matches and even tried to bring a polo match to Tulsa.

Fog Horn and his wife Alice spent much of their life on the road, often with their children in tow. Most of their time was spent working in Texas and Oklahoma. In 1917, Foghorn was an announcer at a bronco riding competition between soldiers at Fort Bliss, near El Paso, and area cowboys. The soldiers held their own.

Fog Horn Clancy lived in Fort Worth between 1919 and 1937. In October 1920, Foghorn was in Fort Worth, but his 14-year-old son was not. Foghorn Jr., as he was called (one word), had taken some old clothes and the ropes he used in roping contests and disappeared. It took almost a month before his father found Foghorn Jr. on a ranch. The story about the boy’s discovery noted that he would take part in the Fort Worth Fall Rodeo in a few weeks. One wonders if the disappearance might have been a publicity stunt.

A move to rodeo production

Fog Horn continued to announce at rodeos, but started to move into production and management. The year 1923 proved to be a busy one when he was named manager of the rodeo at the Southwestern Exposition and Fat Stock Show and formed his own company called “Foghorn” Clancy’s Cowboy Rodeo. The lead-up to the Fort Worth rodeo featured an iconic event – when cowboy Bryan Roach rode his horse Dynamite across the floor of the Hotel Texas.

Fog Horn was part of the staged affair. Now, that was definitely a publicity stunt!

In 1923, Fog Horn also managed the “Passing of the West” rodeo which played in several locations on the East Coast and featured legendary rodeo and wild west show performers. His oldest son Fred Jr. was now 17 and a young man, so Fog Horn pressed his youngest son, John P. Clancy, into duty as the new Foghorn Jr.

The year 1925 brought change. Fog Horn was selected to produce the State Fair of Texas rodeo in Dallas, but it was a different event that changed his future. The loudspeaker system was invented. That meant that producers didn’t have to pay for the rare person with both announcing skills and a loud voice. Now all they needed was a person who could speak well and a loudspeaker system. It was a lot cheaper to hire locally.

Fog Horn had a strong interest in the business of rodeo, but he wasn’t always successful. In 1926, he announced plans for a 200-acre winter rodeo training facility on a ranch just northeast of Fort Worth. Claiming that one-third of the “top-notch” rodeo performers already currently wintered in Fort Worth, he thought that it was a sure bet. It wasn’t.

As the Great Depression hit and jobs dried up, Fog Horn was pushed toward bankruptcy. Over the years, he had known and worked with many western celebrities and promoters, including Roy Rogers, Pawnee Bill, Tex Austin, Gene Autrey, and Will Rogers. Fog Horn pivoted toward publicity and journalism, writing promotional materials for his friends in the business. He also wrote a rodeo column for the Star-Telegram.

In 1937, Fog Horn and Alice moved to Waverly, New York, to live near his oldest son. He wrote a book about his rodeo experiences in 1952 called “My Fifty Years in Rodeo: Living with Cowboys, Horses and Danger.” It quickly found a following because of its first-person stories about the development of the rodeo industry. Today, copies sell for $300 and up.

Stock show exhibition

Trinity Terrace, 1600 Texas St., will host an exhibition of historical Stock Show memorabilia from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily between Jan. 10 and Feb. 3. Many of the items — including photographs, promotional items, jackets, and badges — are drawn from Fort Worth collector Dalton Hoffman’s personal holdings.

Carol Roark is an archivist, historian, and author with a special interest in architectural and photographic history who has written several books on Fort Worth history.