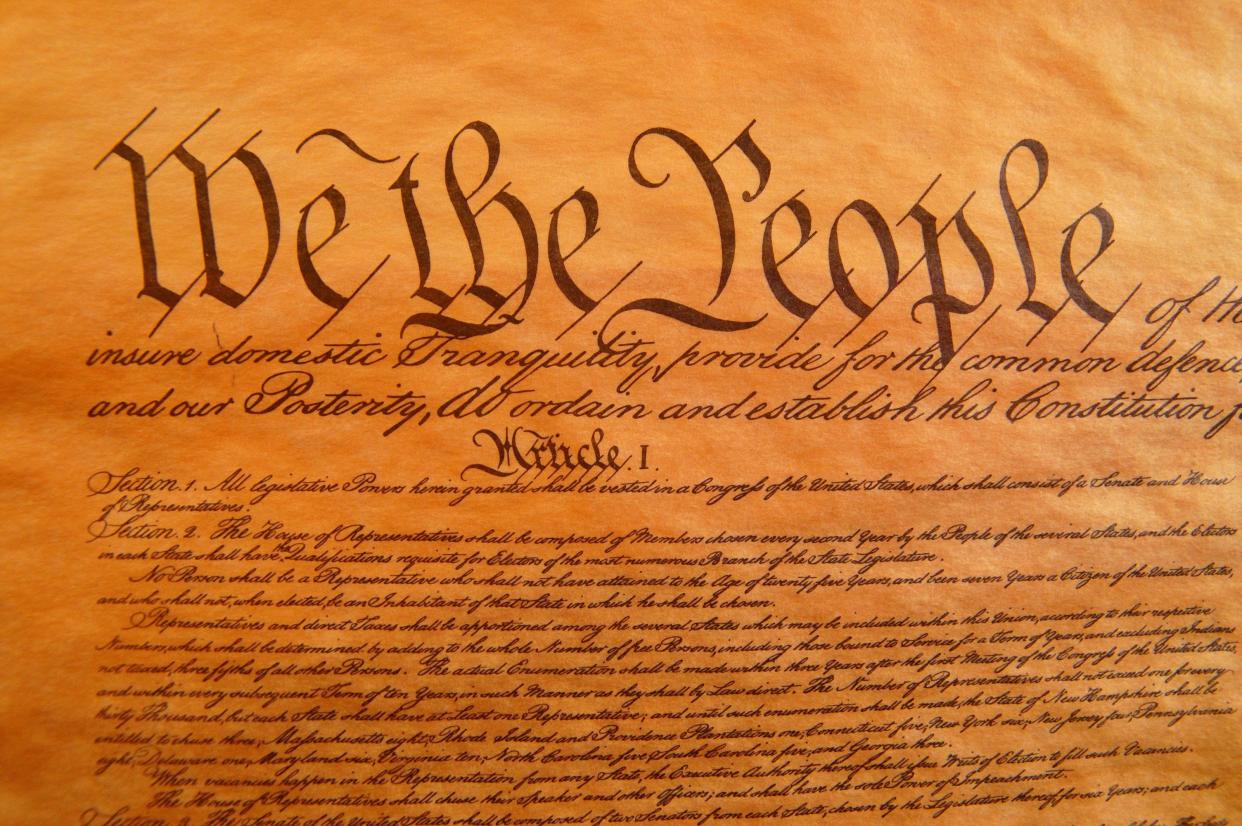

It's time to read your U.S. Constitution

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

We’ve just come through “Constitution Day,” a celebration of the U.S. Constitution ignited by the legislative efforts of Sen. Robert Byrd, Sen. Fritz Hollings and others back in 2004.

Locally, it’s been a tradition in my department since 2010 to have the first-year students start their college experience by imagining, planning, and creating a campus-wide event focused on one central point from the document. It’s a party for the nation, in some ways, but it has a narrowly focused agenda: to place into the hands of the public that very document so often invoked.

And get ‘em to read it, too.

Despite over 240 years of republican government (the political theory kind, not the party) there’s still a kind of weird nostalgia for monarchy that our founders would have likely found a bit peculiar. Impulses towards hereditary reward have always played an important (if somewhat muted) role in the American polity. But despite the best efforts of some families to dominate the political arena, they still have to be elevated by the vote of citizens. We do not anoint leaders via random genetics. That would be unconstitutional.

Republics are rarely founded by “the people.” When the Romans dumped their last King (the hapless Lucius Tarquinius Superbus the folks who did the unloading were not the unwashed masses, carrying pitchforks and torches. They were a sly conspiracy of tin-pot nobles, irritated by being kept from the reins and levers of power. One of the reasons that Tarquin was so difficult to unseat was because “the people” were happy with him as a major counterforce to these same aristos. When the King was dethroned, the would-be boyars recognized that for this transition to survive the masses had to be placated – and they did so with a series of reforms that granted them at least the stage dressings of political power: a constitution with republican forms in place.

Ours is much better. The reforms were and are real.

As is often the case with ancient legends, we’re not sure whether Tarquin was a historical figure or some oddball allegory for other events. What was actually in the original constitution of Rome can only be roughly estimated. We have the massive advantage of actually having the history of our “founding” in hand, along with the original documents and records of the gathering (of mostly colonial aristocrats) that wrote them. We also have the letters of the founders to each other - a great timeline of the debates in the convention itself, and a stunningly complete history of the deliberations and major considerations over whether or not states should ratify it.

All of that “extra” may be only of intense interest to historians. The public may be excused for not bothering with it much, but at rock bottom we have the original document itself, and all of the modifications and adjustments to it that have accrued over the last two-plus centuries - all of it within about four pages of text – six, if you include the Amendments.

The problem is few seem to read it. So, Constitution Day.

There’s a sequel to the Tarquin story: The Romans did not do away with Tarquin after his job was eliminated (though it was a fashion of the time to throw people off cliffs for political error) and he came back, several times, sometimes with an army at his back.

Under their new constitution, the Romans exiled him - and all others who would be king - permanently.

There are lots of things we do not agree on, but while we hedge on science, dispute over evidence, wonder if the earth is, indeed, flat the Constitution of the United States is a black and white fact. It is open in spots to interpretation and dispute, but there can be no “interpretation” without agreement on what it actually says.

R. Bruce Anderson is the Dr. Sarah D. and L. Kirk McKay Jr. Endowed Chair in American History, Government, and Civics at Florida Southern College and Miller Distinguished Professor of Political Science. He is also a columnist for The Ledger and political consultant and on-air commentator for WLKF Radio in Lakeland.

This article originally appeared on The Ledger: It's time to read your Constitution