Times-Union analysis shows minor shift in Black residents from 'racially gerrymandered' districts

Jacksonville City Council members did not discuss race as they fulfilled a federal court’s order by redrawing district lines earlier this month, but if they had, they would have seen a new map does not make significant changes in shifting Black residents from four districts that a judge ruled were racially "packed."

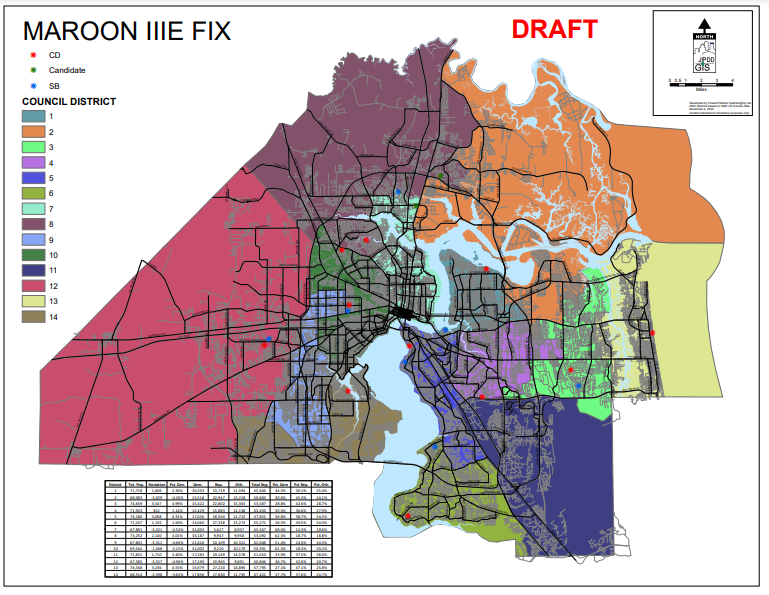

As a federal judge considers the new boundaries approved in the latest map, a Times-Union review of the available racial data shows a statistically minor move of Black residents and their voting power from four Northwest Jacksonville districts to other City Council districts.

U.S. District Judge Marica Morales Howard ordered a new map after finding the city unconstitutionally packed Black voters by drawing City Council districts in a way that “confines the voice of Black voters” to the Northwest Jacksonville districts.

In the original map that the City Council approved in March, the four districts were home to about 173,000 Black residents.

Forced by Howard to redraw the lines after she said the original map used racial gerrymandering, the council backed a map on Nov. 4 that would result in roughly 169,000 Black residents in Districts 7, 8, 9 and 10, a reduction of 2.4%.

New map approved: Jacksonville City Council approves a proposed redistricting map after twists and turns

Original map struck down: Federal judge orders Jacksonville to redraw City Council district lines for 2023 election

Nate Monroe: Under judicial cloud, Jacksonville City Council tries yet another gerrymander

Marcella Washington, a Jacksonville resident and retired political science professor who is one of the plaintiffs suing the city, said the city did not succeed in unpacking the districts.

Washington spoke at a Cuppa Jax event on Nov. 9 detailing how the new map still packed Black voters and expressing her frustration that City Council members “did not even consider” the “Unity Map” put forth by the civil rights groups and residents suing the city.

That map would have shifted a much higher number of Black residents into other districts.

“I got the feeling as if they were looking at me like, ‘Why are you here? Why are you even bothering us with this?’ as if it were their own sacred responsibility to do this on their own,” Washington said.

Until Howard rules in December, the city will not know if a difference of around 4,000 residents will meet the test of the judge’s constitutional review. One of the key legal questions in the federal case will be how much weight Howard puts on racial data in assessing the city's proposed map.

She could accept the city’s map, or alternatively, approve a map put forth by the civil rights groups suing the city, or even commission a newly made map not involving either group.

How the city’s new map affects Black voters in the questioned districts

Howard wrote in her Oct. 12 order that the city has used race as a “predominant factor” for decades in drawing boundaries for Districts 7, 8, 9 and 10. She did not order any specific changes to the boundary lines but said if the city is going to keep using race as a driving force for boundaries, it must make sure that use of race is “narrowly tailored.”

When the City Council hammered out a new map in four days of redistricting meetings, it deliberately kept race out of the conversation and told Howard in a recent court filing, “The race of the potential district constituents was not considered.”

The city did not provide any public information about the racial makeup of the districts. Instead, the city’s redistricting expert showed detailed data about the breakdown of registered Republicans and Democrats in each council district, emphasizing the partisan side of redistricting.

The Times-Union made a public records request for any documents the city has for the racial makeup of the districts in the proposed map submitted to Howard. The city’s Office of General Counsel responded by saying state law exempts such records from disclosure when they are attorney-related “work product” prepared for a court case until that case concludes.

But analysis of the proposed map using the Dave’s Redistricting site shows how the racial breakdown would change.

The racial makeup of the two maps, initially reported by Jacksonville online publication The Tributary, illustrates how boundary changes in Districts 7, 8, 9 and 10 would result in increasing the number of Black residents in District 7, maintaining the same level of Black residents in District 8 and reducing the number of Black residents in Districts 9 and 10.

When all those changes are taken together, the total number of Black residents in the four districts is 169,050, which would be a 2.4% decrease from the March map that had 173,131 Black residents in those four districts, according to the Dave’s Redistricting data.

In Howard’s order requiring a new city map for the upcoming spring elections, she wrote that by overloading the four districts with Black voters, that pulled Black voters out of neighboring Districts 2, 12 and 14.

She said the city’s original map would have assured that Districts 2, 12 and 14 would not have a sufficient number of Black voters for them to have a “meaningful impact on any election or a meaningful voice on any issues of concern.”

In the new map approved by the City Council, Districts 2 and 12 would have fewer Black residents than the one from March.

District 12, which covers the southwest corner of the city, would have 21,709 Black residents, a decrease of 3.3% from the 22,453 in the March map.

District 2, which contains a chunk of the Northside and crosses the St. Johns River into East Arlington, would have 13,742 Black residents, a drop of 8.4% from the 14,995 in the March map.

District 14 would gain Black residents in an area that covers the Ortega and Argyle Forest areas. It would have 21,214 Black residents, a 41% increase from the 15,046 in the March map.

How the city’s proposal compares to the 'Unity Map'

In contrast to the city’s proposed map, the civil rights organizations that successfully sued the city presented the Unity Map that would have resulted in 156,692 Black residents in the four Northwest Jacksonville districts, a reduction of 9.5% from the map that the City Council approved in March.

Like the city’s proposal, the Unity Map would reduce the number of Black residents in District 2, but it would put far more Black residents in Districts 12 and 14 than the City Council map would.

District 12 would have 29,442 Black residents (7,733 more than the city’s new map), and District 14 would have 25,724 (4,510 more than the city’s).

The council rejected the Unity Map. In a court filing, the city said the rejection was based on the Unity Map putting council incumbents in the same district, not following Interstate 295 as a boundary line for districts, mixing “dissimilar areas” together such as rural and urban parts of the city and disrupting the “current political balance between Republican and Democratic members” on City Council.

Times-Union reporter Hanna Holthaus contributed to this story.

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Jacksonville redistricting results in small move of Black residents