Can a tiny Franklin County farm town just stop being a city? What leaders are saying

Is the tiny Franklin County town of Mesa on the path to disincorporation?

Probably not, but that hasn’t stopped rumors from swirling as the city deals with the fallout from years of financial stumbles, a 20-year lawsuit, hiring struggles and suspected embezzlement.

Mesa is a small agriculturally-driven community of about 490, half an hour north of Pasco.

It began as a stop between Eltopia and Palouse Junction in 1883, and was first homesteaded by the Poe family in 1887, two years before Washington became a state.

Mesa was incorporated in 1955, just a few years after the Columbia Basin Irrigation Project brought water and the post-World War II G.I Bill Reclamation Settlement program brought veterans and their families eager to start a new life farming the basin.

It was a chance to turn difficult land into a legacy through hard work and many veterans were eager for the opportunity. In the Columbia Basin, an average of more than 300 veterans applied for each farm available in 1952.

Ray Bailie was one of the veterans who chose to call Mesa home, but he had connections to the area even before the war. He spent some time in Mesa before the war working for the Poes, who were family friends, according to his 2008 obituary.

He left to serve in the Navy, and married Lucille Poe, then they decided to return after the war to make Mesa their home.

Bailie became a prominent cattleman and farmer in his own right. He would go on to become one of the town’s first mayors and staunchest advocates.

Today, Mesa still holds strong to its agricultural roots, but years of financial turmoil led to frequent turnover for both elected officials and employees, and rumors that the town may need to take drastic measures.

The claim the city could be on the verge of disincorporating came up at a recent Port of Pasco meeting during a discussion on regional economic development.

While the comment by a Connell chamber of commerce official was not the first time the possibility has been mentioned, it was the most public discussion to date.

The official later declined to talk about the issue with the Herald.

Mesa’s mayor flatly refutes the rumors, but didn’t want to be interviewed about the challenges and future of the community.

Mayor Jim Cronenwett has been in the role for about a year, after the previous mayor resigned. He’s also got a new city clerk/treasurer who is working to fix issues found in Washington state audit.

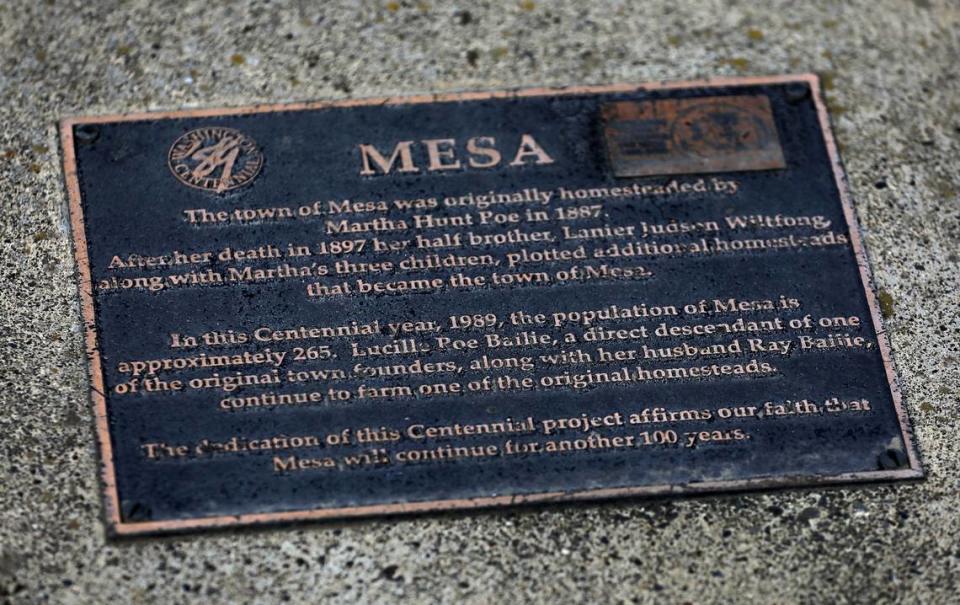

A plaque celebrating Mesa’s history and the Poe and Bailie families sits in front of the town’s welcome sign. It was placed during Washington’s centennial in 1989, and declares, “The dedication of this Centennial project affirms our faith that Mesa will continue for another 100 years.”

What’s happening?

The past few years have been rough for Mesa’s elected officials and employees. The current city clerk/treasurer is at least the fourth person in that role in the past five years.

The city lost a long-running public records lawsuit in 2018, leading to a ruling to pay former Mayor Donna Zink $175,000, but that was later largely reversed by an appeals court. It’s unclear how much the city had to spend in attorney’s fees over the nearly 20 years of the lawsuit, which was first filed in 2003.

In 2022, former Mayor Merlin Giesbrecht told the CrossCut news outlet that their former treasurer had left potentially hundreds of thousands of dollars in COVID-related funds on the table. They were funds he said they didn’t know they were even eligible for, but the city could have used. Instead Mesa joined a short list of small towns that didn’t apply for them at all.

Not long after, the city’s then-clerk/treasurer, Danni Speelman, was arrested for using her position to commit theft. She is accused of stealing money from the city through a series of fake transactions over the course of the six and a half months she worked for Mesa. Her trial is set to begin in October.

Court documents show that the scheme was caught when a Housing Specialist for Goodwill of the Columbia noticed she had used Giesbrecht’s address, without his knowledge, for the accounts she was fraudulently collecting money for, according to court documents.

By September a new clerk/treasurer, James Gimenez, was in the role, but dealing with the theft and was also immediately wrapped up in an audit from the state auditor’s office because the city had not submitted annual reports since 2020.

Included in an October 2022 letter of findings, the city told the auditor’s office they had little information on what had happened and how to proceed.

“In 2021 our City Clerk/Treasurer resigned on June 1st. She left not telling anyone about the annual report that was due or what it was about. By 2022 we were on our 3rd new clerk with little experience who loved to overlook emails she didn’t understand.”

Shortly after Speelman left, Giesbrecht appears to have also resigned, leading to Cronenwett stepping into the position. By the time the city responded to the auditor’s office, Gimenez also had left.

“Our books are not up to date and we don’t know where to start. Any help or advice would be greatly appreciated. As far as when the 2021 and 2022 reports will be done, maybe six months.”

The audit found that the city “lacked adequate internal controls over financial reporting to ensure compliance with timely annual report submissions.”

The current clerk-treasurer told the Herald that she had been able to get the city’s books up to date over the past year.

Disincorporation rumors

Is all that enough to lead to a small town dissolve? Not likely, according to Washington law.

In Washington, state law lays out three ways a city can be disincorporated, and they are all exceedingly rare and legally difficult to navigate.

To voluntarily disincorporate a city must either start the process via a citizen-led petition or through a city council resolution. Both methods then require the proposal to go before the county boundary review board before going on the ballot for a full vote of city residents.

The involuntary method is only used if a city fails to place its regular elections on the ballot for two years or if those elected officials fail to qualify and the function of the government ceases, according to state law.

The most common belief seems to be that financial troubles or difficulty keeping elected officials could prompt the city of Mesa to make such a move, but only the latter could push the town toward disincorporation. There is nothing in the law that would force the city to disincorporate over financial obstacles.

And while Mesa has seen turnover in elected officials, they have not failed to hold regular council elections. That rules out involuntary disincorporation.

In the past 50 years, an attempt to disincorporate has only been attempted twice in Washington, and the more recent attempt failed.

In 1972, Westlake in Grant County disincorporated.

More recently, in 2009 an effort was made to disincorporate Spokane Valley, but the community members pushing for the vote failed to get enough signatures to place it on the ballot. There has never been an involuntary discorporation in Washington, according to a 2009 memo from the Spokane Valley City Attorney’s Office.

On top of that, it’s also not a way the city could potentially bypass financial obligations or offer a big tax break to property owners.

State law makes it clear the city’s taxes will continue to be collected by the county until debts are paid, and then levies are limited to 50 cents per $1,000 of assessed value.