Is Tippecanoe County's aquifer Central Indiana's long-term plan for water needs?

LAFAYETTE, Ind. — The concerns over Indiana’s Economic Development Corp.’s Lebanon LEAP project drew out hundreds of residents who filled up the hall of Church Alive to voice their concerns on Thursday night.

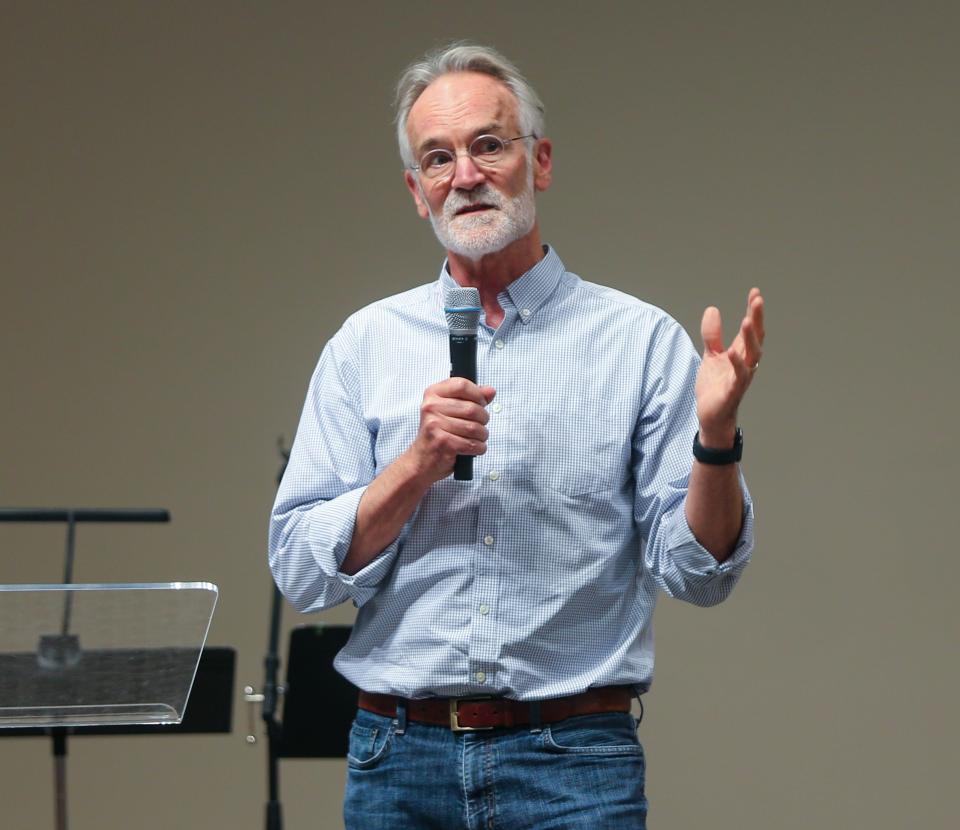

The church had invited John Cochran, a representative from IEDC, and Jack Wittman, vice president of eastern water for INTERA — the company that recently conducted the field testing on the aquifer in Lafayette — to discuss INTERA’s findings and answer questions from locals.

Cochran addressed IEDC’s reasoning for examining the aquifer near the Granville Bridge in Lafayette and expressed the importance of this project for the State of Indiana.

In prior discussions about the LEAP district, the IEDC explained that the state had purchased land near the Wabash River aquifer with the hopes of extracting water and piping it to Lebanon to help support the development of an economic district in Boone County.

According to earlier reports, the project was expected to pipe millions of gallons of water a day to Lebanon, between 10 million and 100 million gallons.

But apparently, according to Cochran, that appears to be the state’s short-term plan regarding the aquifer. The long-term plan seems to be a project to supply central Indiana with water in the future.

“In 2019, a study from the Indiana Finance Authority [sic] that all project a future water shortage in the central Indiana region, that is not sustainable for economic growth beyond the next 50 years or so,” Cochran said.

“That’s sort of the long-term situation of water in central Indiana. In the long term, the state’s going to look for ways to bring water into central Indiana from somewhere.

“The state has gotten a lot of interest from companies, large companies who are looking to make large investments in the area, in the LEAP district. Right now, the IEDC is doing its due diligence in the area we’re looking for potential water sources, sustainable water sources for the region and locally and examine what could be available for economic development.”

How much water could be pumped from the aquifer?

The primary reason why the IEDC began evaluating the water-tapping potential of the region was due to the county’s proximity to the Teays Bedrock Valley aquifer system.

The state wanted to evaluate how much water it could sustainably withdraw from the aquifer that is located below Tippecanoe County, as well as determine at what rate it could pump water from the aquifer while maintaining reasonable water table levels.

Scientists also wanted to determine the location that would be the most efficient area to pump, how much water could be pumped from the aquifer and from the river, and what the immediate effects of pumping would do to the Wabash River.

“The focus I see up in Tippecanoe County at this point with the water is really two-fold," Cochran said. "A. To determine how much water the aquifer can sustainably yield; and two, do a preliminary work to determine how to move the water to maximize its beneficial use for the region."

“So if we have a huge end user that decides to come into LEAP, we want to look at what it would look like to move water potentially from the aquifer here to that district.”

Before handing the mic to Wittman, Cochran noted that the state’s “goal is not to benefit one area at the expense of the other. That’s not what we do.”

This statement was answered with laughter from the residents in the audience at Thursday’s meeting.

INTERA's findings

Wittman, the vice president of eastern water for INTERA, spoke to the audience about the company’s findings from their testing of the Lafayette aquifer.

“Central Indiana is not facing a shortage. It’s facing kind of a limit in the ways it they can get water, because the rivers in that part of the state are smaller than they are in other parts of the state. And they’re using really creative methods in central Indiana to maintain the supply of water,” Wittman said.

“They’re using storage, which is historically been what Central Indiana has done. They have reservoirs that they built as time goes on, and that has been effective for that part of the state. And they are attempting to do that too with these deep mines sort of quarry and converting those into reservoirs.”

INTERA conducted three days of testing at the site near the Granville Bridge in hopes of gaining a deeper understanding of the properties of the aquifer.

Scientists set up two testing wells and 17 monitoring wells across a 50-acre parcel of land to observe the immediate effect the extraction of the water would have on the surface area surrounding the aquifer or the river levels.

Over the course of three days, scientists pumped water out of the aquifer at a rate of 1,420 gallons per minute from two testing wells to obtain a variety of data. The water used for testing was pumped into the river.

Scientists found that just for one well, the lowest amount of water that they were able to extract was more than 15 million gallons of water a day.

However, they did determine that the maximum yield scientists could withdraw from both wells was around 45 million gallons of water a day.

Although scientists determined the maximum yield of water that could be withdrawn from the area, they ultimately don’t believe water from this aquifer could sustainably be extracted at that rate.

“We aren’t thinking that this is a place that you can pump two million gallons, we might want to put multiple wells along the river or evaluate how many wells, John said it earlier, how much can’t you pump from this piece of land,” Wittman said.

When evaluating the geological data that they extracted from these tests, INTERA was able to determine that the aquifer materials were uninterrupted and were not segmented into an upper or lower aquifer by clay.

The scientists discovered that the aquifer was primarily made of sand and gravel and that the Wabash Alluvial Aquifer sits on top of the Teays Bedrock Valley Aquifer.

The purpose of testing was to determine how easily water from the aquifer could travel through the sand and gravel and how it could affect the observed water level changes.

The data that INTERA gathered from their field testing allowed them to create a model to showcase and determine how pumping would alter the water level changes in the area.

After everything was said and done, one aspect of the aquifer that was not discussed was the rate in which it takes for the aquifer to recharge.

Aquifer recharge or aquifer storage and recovery is this idea of the processes it takes for an aquifer to be replenished from other sources of surrounding groundwater.

Affects of the testing on the water

This lack of information was something highlighted in the questions asked by residents who lined up after Wittman’s presentation.

Beyond the notion of questions regarding IEDC’s intention with the county’s resources and aspects of Wittman’s presentation, several residents spoke up on how the testing of the wells affected their water supply.

One individual noted that when IEDC was conducting their tests, his water developed a sulfur-like smell, while another individual’s neighbor had their water filter fill up with sand and gravel due to the testing.

Much of this information Cochran and Wittman didn’t know had occurred.

One point that was brought up during the Q&A portion of the event that stumped both Cochran and Wittman was this concern of setting a precedent of tapping for water in aquifers that are adjacent to rivers.

The resident noted that although extracting water from the aquifer in Lafayette could potentially be sustainable if future industries discover that this method of extracting water could be a cost-effective method to obtain water, what regulations or laws does Indiana have put in place to stop industries from building along the Wabash River to extract water.

At some point, if 100 million gallons of water are being extracted from a multitude of sources along the river, it will eventually begin to negatively affect the river, the resident told Cochran and Wittman.

When asked how they would stop this from happening or what would happen if this situation occurred, they said more testing was needed.

Noe Padilla is a reporter for the Journal & Courier. Email him at Npadilla@jconline.com and follow him on Twitter at 1NoePadilla.

This article originally appeared on Lafayette Journal & Courier: IEDC shares with locals its reasoning for testing Lafayette's aquifer