TLH 200: Tallahassee closed the pools to keep civil rights activists quiet. It didn't work

After integration, many cities in the South decided to just shut pools down rather than let Black people in, including Tallahassee.

During the summers of 1964-1967, the city commission closed public swimming pools to avoid integrating them, according to Democrat archives.

The original Robinson-Trueblood Swimming Pool on Dade Street was dedicated May 18, 1953. Along with pools at Myers and Levy parks, Robinson-Trueblood was one of the first three pools built by the city, all in 1953.

The only pool Black residents could swim in was the Robinson-Trueblood pool.

"In the twilight of segregation, Tallahassee fathers built a city swimming pool for Black residents and hoped it would quiet their increasing demands for integration," wrote Tallahassee Democrat writer Gerald Ensley in 2001. "It didn't work."

Wade-ins, where African Americans would enter whites-only beaches and pools, were met with resistance and violence from Tallahassee’s segregationists and law enforcement.

FAMU student Patricia Stephens Due, a notable civil rights activist in Tallahassee during the Jim Crow era, watched her sister Priscilla get kicked in the stomach by a police officer at a wade-in at a white’s only public pool.

The first closing came in summer 1963, after Due and other Black college students tried to integrate the pools at Levy and Myers parks. The City Commission re-opened the pools in spring 1964 — only to shut them down again in July after local Black children attempted to integrate the Levy Park pool.

That’s when the city decided to shut down all the public pools for almost four years.

“People always misunderstood what the struggle was about,” Due told The Miami Herald in 1990. “It was never about Black rights. It was a fight for human dignity.”

More than 150 white residents took out a full-page ad in the Tallahassee Democrat, asking for the re-opening of the pools. Letters poured into the newspaper; one writer suggested Tallahassee assign a role to each of the three pools: white-only, Black-only and integrated. Tallahassee Democrat editor Malcolm Johnson called for the re-opening of the pools in 1965, writing that residents could "vote with wet feet" about integration.

In August 1967, the City Commission reluctantly allowed a straw ballot on the issue — but ignored the results after voters narrowly approved the re-opening of the pools.

Finally, on April 9, 1968, five days after civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated and riots erupted in Tallahassee, the City Commission voted 3-1 with one abstention to re-open the pools.

Robinson-Trueblood a vital resource for the community

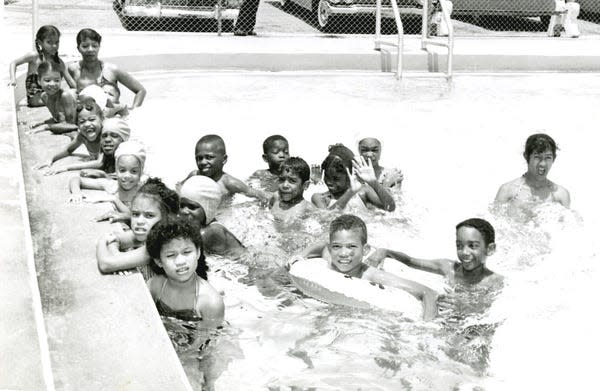

The Robinson-Trueblood pool was vital to the neighborhood. Admission was 15 cents for children. The pool reached capacity early on hot days, and children would wait in line until others left so they could be admitted. Teens would gather for Saturday night "splash parties" and Sunday afternoon dances in the pool bathhouse. Swimming and diving teams were formed. Black churches held baptisms there.

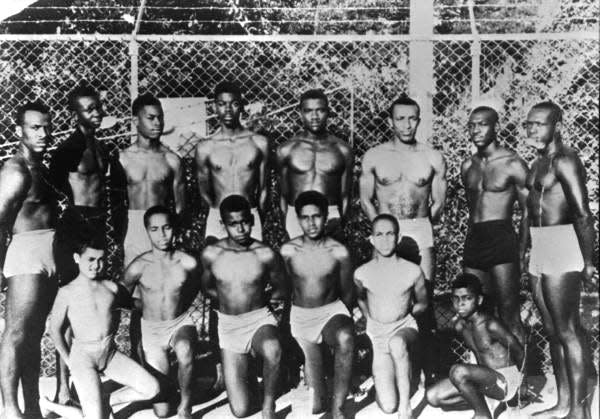

Thousands of Black children took swimming lessons at Robinson-Trueblood, which offered local Black residents their first opportunity for formal instruction. The Dade Street Dolphins boys and girls swim team competed all over the state against other Black swim teams, winning the Orange State championship in the late 1960s

Bishop Holifield, 76, was a member of the Dade Street Dolphins.

Holifield, a retired general counsel at Florida A&M University who was also a leader during Tallahassee’s civil rights movement, fought to reopen the pools.

He remembers swimming up to three times a day during the summer at the Dade Street pool.

He and other members were part of the Black community that campaigned and held a straw poll to determine whether or not the people of Tallahassee wanted to reopen the pools. A majority did.

Historically in the U.S., Black communities were left out of public swimming opportunities, like in Tallahassee. Racist laws enforced by police during segregation kept Black people from swimming in white pools, community centers and public beaches, and the decades of racist policies led to a deadly result: today, Black children are three times more likely to drown than white children, according to the YMCA.

Holifield said the Robinson-Trueblood pool allowed him to not only learn how to swim, but he also learned lifeguard techniques.

“We reduced drownings in the Black community,” he said.

“Everybody needs to know how to swim,” he added.

In 2011, Ensley wrote the pool has become "hallowed ground" for the civil rights movement. It's also become a tradition for residents to gather for the annual Robinson-Trueblood pool reunion.

"Tallahassee is a better place to live today because of its civil rights movement," retired Florida A&M professor and author Charles U. Smith told Ensley at the time. "The pools were part of that."

This story is part of TLH 200: the Gerald Ensley Bicentennial Memorial Project. Throughout our city's 200th birthday, we'll be drawing on the Tallahassee Democrat columnist and historian's research as we re-examine Tallahassee history. Read more at tallahassee.com/tlh200. Email us topic suggestions at history@tallahassee.com.

This article originally appeared on Tallahassee Democrat: In 1960s, Tallahassee closed swimming pools to thwart civil rights