Tom Brady-like: Archery to woodworking, Nocatee Boy Scout gets every single merit badge

On his way to getting all of the 138 merit badges that a Boy Scout can possibly earn, Tre Peterson of St. Johns County learned a good deal about many things, like architecture and aviation, backpacking and basketry, composite materials and crime prevention ... well you get the picture.

He figures he’s spent some 1,500 hours completing his badges. Some were easy, like fingerprinting: An hour, perhaps.

Others tested him, mightily. Consider the bugle: He'd played the trombone in middle school, so how hard could it be?

Very.

Turns out the mouthpiece of a bugle is much smaller than a trombone's, and there are no keys to play to change notes. He did eventually learn all 10 required bugle calls, but that meant much practicing was involved.

His father, Tom, got a little nostalgic. “It sounded like whales being attacked, upstairs,” he said.

A visitor, eager to see that replicated, asked if Tre wouldn't mind playing some bugle, right there, right then. He grinned, and shook his head with relief.

“I gave the bugle back," he said.

A Boy Scout adventure

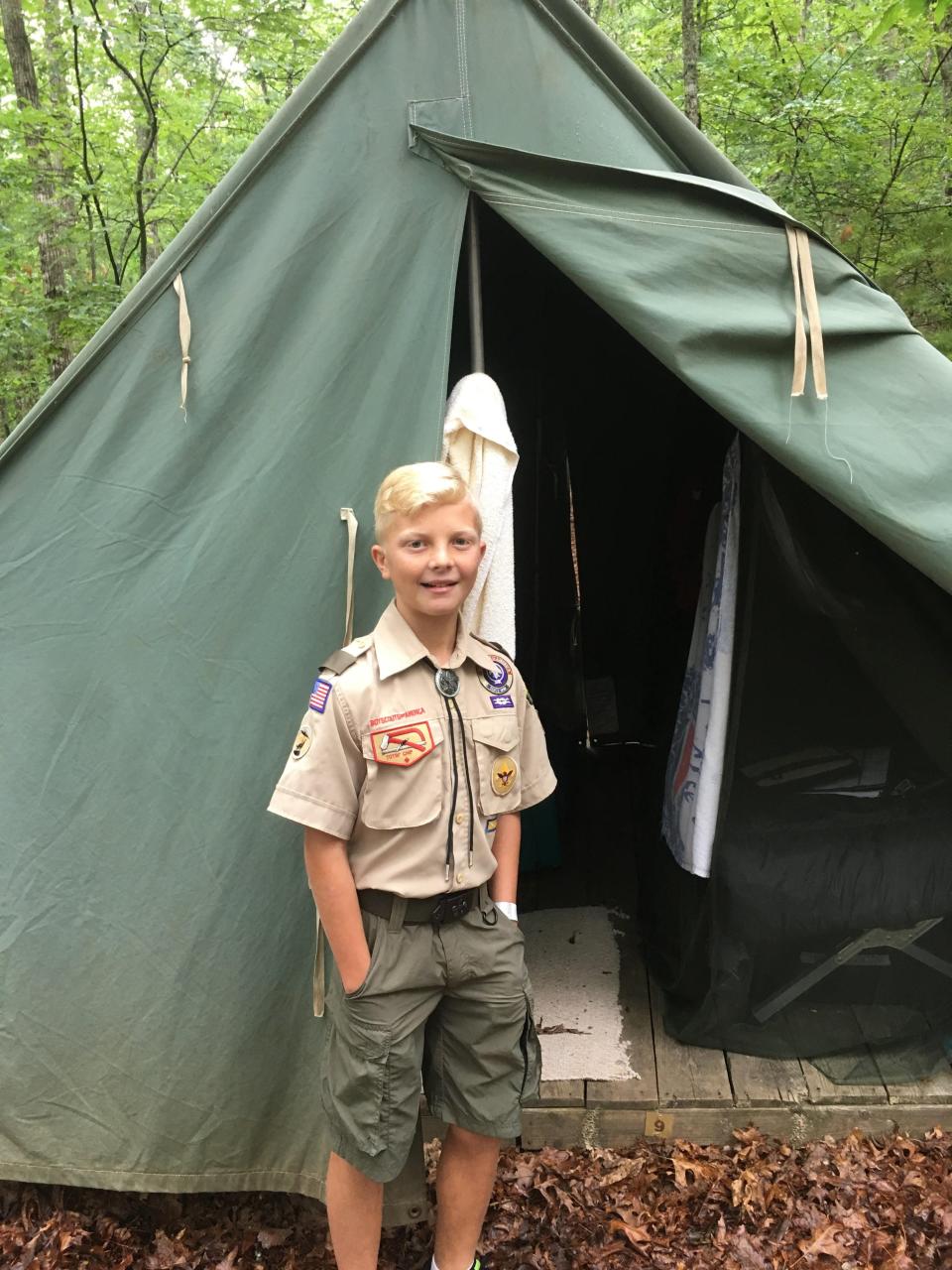

Tre Peterson, from Troop 277 in Ponte Vedra Beach, turns 18 next month, at which point he will have aged out of Scouting. He has not been a slouch.

He became a Cub Scout in first grade, moved into Boy Scouts in fifth grade and earned Eagle rank by the end of seventh grade after having achieved 86 merit badges, about four times as many required of an Eagle.

His dad, and pretty much everyone else, encouraged him to get all 138. He was more than halfway to that goal anyway and still had almost five years to go.

It's an exceedingly rare feat: The Petersons were told that in the entire history of the Boy Scouts of America, fewer than 550 people have earned every merit badge — less than .00042% out of about 130 million Scouts who ever scouted.

Mark Woods: More than 50 years later, 70-year-old Jacksonville man becomes an Eagle Scout

Kelvin Williams, CEO of the North Florida Council of Boy Scouts of America, tried to put Tre's achievement into perspective: "In layman’s terms, if the Hall of Fame had another level, he’d be above the Hall of Fame," he said. “He entered the Hall of Fame and then went Tom Brady on everybody.”

Williams has been in regional and national leadership roles for the Boy Scouts for 22 years and can count on one finger — or possibly two — those he's met who've earned every merit badge. "I only know of one or two people that I remember," he said. "I can remember vividly one, and maybe another. And Tre would be three.”

Paperwork and hard work

Getting merit badges requires a lot of documentation and often detailed, time-consuming work — camping, for example, requires 20 nights outside. But earning those badges is not the only thing Tre does.

He works Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays from 6 to 8 a.m. maintaining the course at Palm Valley Golf Club, then goes to Ponte Vedra High School. He plays golf and has gotten into pickleball, and has, he says, time to hang out with friends.

"He's a perfectionist," Tom Peterson said.

Tre, who lives with his parents and sister in Nocatee, is a third-generation Scout, following his grandfather and his father, a retired Navy captain who later also retired from a financial services company.

Tre teases his father as he credits him for his encouragement. "It's just because I was constantly being nagged by him.” He nodded at his dad, and smiled. “And others. All parents.”

And when he thought of easing up on his quest, he was urged on by a group of Scouting moms. Two moms even joined him on the last part of his hiking badge, a 20-mile trek through Sawgrass.

“All of their kids went to college, so they’re like empty nesters," he noted. "So they chose me as the person to nag. And they knew I was close — I think I had 100, 110 — and they said, ‘You’re doing this.’”

Tre's first badge was veterinary medicine. His last was scuba, which required an expensive trip to Orlando for several days of training and certification.

“I’m just super-relieved," Tre said. "It’s like a weight‘s been taken off, but I’ve also got exposed to so many things that I would never have known, like the welding or the metal work, and I also got to see what I liked. So after the personal management badge, I was like, I want to do finance.”

So he has applied to Stetson University, where he hopes to major in finance

Some of the merit badges Tre has earned

Automotive maintenance: “Just a couple weeks ago my friend called me and he said, ‘My car just broke down. You’re a Boy Scout, I know you know how to do this. Can you come out and help me?’ His dad actually was the one who told him to call me, because his dad knew that a Boy Scout should know these things, and that I was reliable and trustworthy and stuff."

Sure enough, Tre had jumper cables and got the car started.

Citizenship in society: Part of it involved meeting with a group of about 20 other Scouts and having a long conversation about diversity, inclusion, the Black Lives Matter movement and other topics. "That one was a big conversation, just about how we need to bring people together and stop excluding people, how people have feelings and emotions.”

Disability awareness: He went to a neurological center at the Mayo Clinic and met patients going through short-term memory loss or recovering from accidents.

Horsemanship: He did it at a summer camp, where he and other Scouts visited a farmer. “We did everything with him, not just horsemanship. We did animal science — cows, pigs, chickens. We saw a cow get dehorned, we saw a sheep get sheared, a calf get castrated."

Law: He went to St. Johns civil court. In the crowded room, the judge spotted him in his Scouting uniform and asked what he could possibly be doing there. Tre explained, and the judge called him up, where they took photos. “You want to talk about some attorneys who were not really happy!” said his father.

Metalworking: His favorite badge. He was a number of Scouts who worked in a forge, where he made a coat hook, while burning all 10 fingers. "I thought it was cool, he said. "But it wasn't. So for the rest of the week I had bandages on all my fingers."

Moviemaking: He made a claymation movie. “It was just about my Scouting journey. Super simple."

First female Eagle Scouts: Latest historic moment in century of Jacksonville Boy Scouting

“Nuclear science: “That was one of the tougher ones. As a 15-year-old doing nuclear stuff" — at that, he chuckled — "that was a tough badge.” To be clear, nothing hazardous was involved, but among several research projects, he built a model of an atom and did an experiment involving hot dogs, tracking the decomposition of processed and non-processed foods.

Space exploration: A lot of research was involved, but there was some fun too at a Scout summer camp. “We did model rockets, just a typical kit, and then we spent the day just shooting them. I think we had a competition, whose could go farthest or highest or something."

Wilderness survival: Part involved spending a night alone in the woods. He was going to do it over summer camp, but that night it poured. So he ended up doing it later, taking with him just a garbage bag and a rope — which which he made a lean-to tent with the help of sticks — and heading into the thick Florida woods that are preserved behind his house in Nocatee.

“It’s scarier, I guess," he said. "It’s wilderness, not a Boy Scouts summer camp."

It was a long night: “I think I slept maybe two hours. The next day my entire legs were just red and inflamed with bites."

Did he see any critters? “Um, no. Just the typical bugs. The bugs you could see in the wilderness. No bears, no coyotes, no bobcats.”

But you hear noises all night long. “Even in a suburban neighborhood,” he said.

The Boy Scout sash

Tre's Boy Scout sash has no more room to display the merit badges he's earned. They cover the entire front and the entire back. He has five more still to add. Perhaps he'll put them on the inside of sash, he speculates. It's a good thing his mother, Cheryl, is an experienced seamstress.

He jokes: He's been thinking about crisscrossing sashes, like Rambo's bandoliers.

As it is, the whole display of badges gets looks of awe from younger Scouts. He hopes it inspires them, and those thinking about Scouting, which he'd recommend.

"First of all it’s achievable, for the younger Scouts to get into it and experience what it’s like to be in a group, a brotherhood. Then as you grow up you get the experiences you need to become successful in life, in your future, which I think all these merit badges have helped with," he said. "A little bit of experience in each small field, and now I have a big collection of knowledge that I can use.”

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Boy Scout from St. Johns County earns all 138 merit badges possible