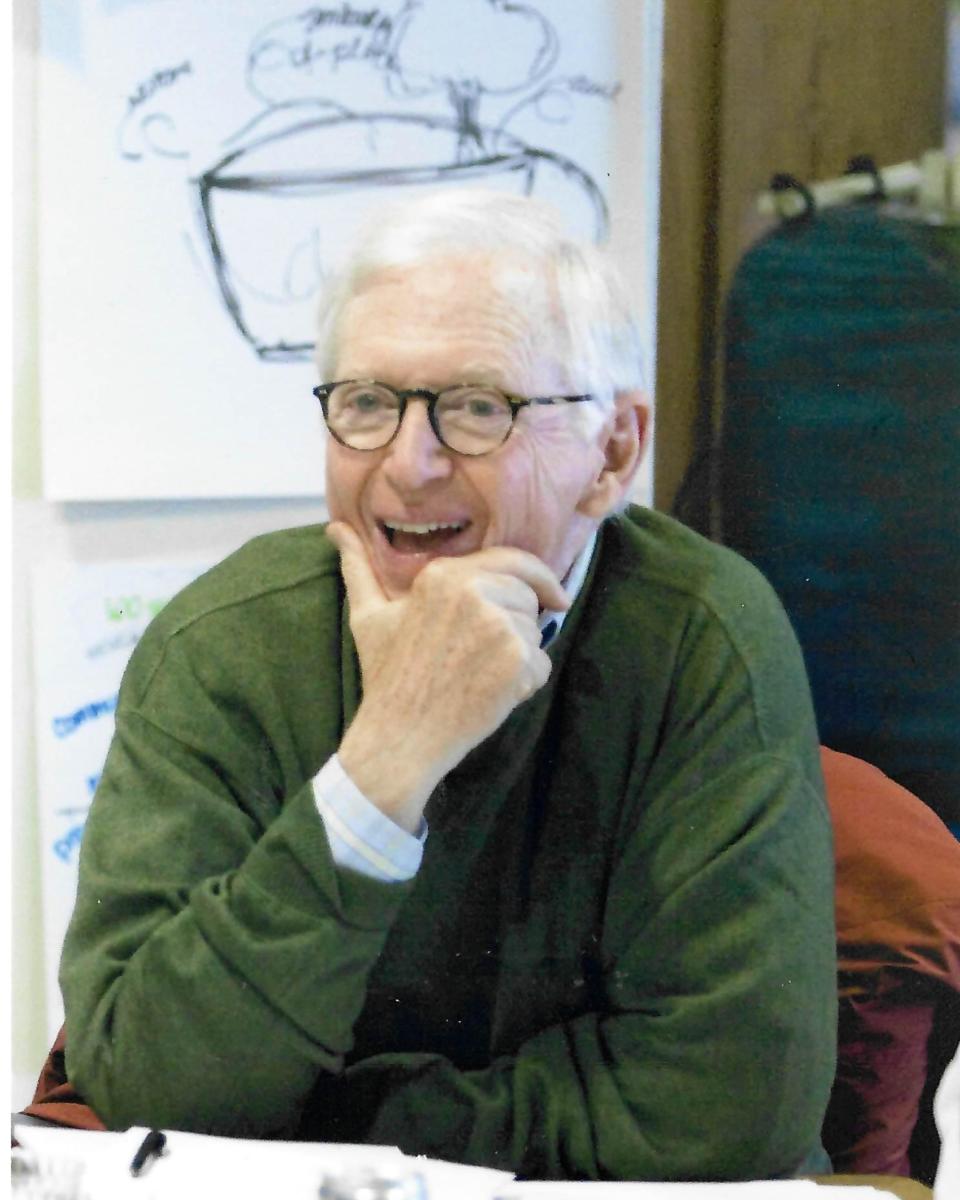

Tom Stoner, Des Moines businessman, philanthropist and rival to Chuck Grassley, dies at 88

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Tom Stoner — noted broadcast executive, longtime Iowa Republican and former rival of Sen. Chuck Grassley — died on Oct. 19 of pulmonary fibrosis.

Surrounded by family in his adopted second home of Annapolis, Maryland, “Tom died the way he lived, with exuberance,” an obituary notes. He was 88 years old.

“He was a really proud Iowan,” says Chuck Offenburger, the Register’s former Iowa Columnist. “Even though he lived the second half of his life mostly out of state, he never lost track of Iowa and always wanted to know and was curious about things here.”

A shrewd businessman, Stoner grew his family’s fortune by founding Stoner Broadcasting, a conglomerate of more than 100 radio stations that he and his partners sold to CBS in 1998, and American Tower Corp., which is one of the most lucrative broadcast and cellular tower companies in the world.

Later in life, he was also a generous philanthropist who supported many causes close to his heart, namely the arts and Nature Sacred, the nonprofit now run by his daughter, which seeks to install green spaces in places in need of nature's medicinal powers.

But he may be most remembered for challenging Grassley in the stalwart Republican’s first campaign for U.S. Senate, marking the last time Grassley faced a serious primary challenge.

Stoner “was a significant political figure in the state,” says Offenburger, “and cut from the same mold as Bob Ray,” a moderate and one of Iowa’s most revered governors, known for welcoming Tai Dam refugees into Iowa in the wake of the Vietnam War.

Having already been an involved businessman, Stoner chaired Ray’s 1972 and 1974 campaigns and became the state’s GOP chairman from 1975 to 1977, leaving to spend more time with his family and, as would be revealed, prepare to mount a 1980 run himself.

The primary between Grassley and Stoner was viewed as “a battle” between the conservative wing of the party, represented by Grassley, and the moderates, represented by Stoner and Ray, the Register wrote at the time. A number of national and single-interest groups, including anti-abortion activists and gun owners, came out in support of Grassley.

That year, more than 55% of registered Republicans, up from the usual 20% to 30%, came out to the polls for the “heated primary.”

The heat, however, was tepid for Stoner. He lost by 32 percentage points and carried only nine of the 99 counties.

“The very conservative elements are certainly stronger than they have been in any recent election year,” Stoner told the Register on the night of the primary.

But the loss didn’t stop Stoner from continuing to affect politics both directly and indirectly. Indeed, many who know him said he never lost the positivity he exuded while in the heady final days of his run, when he’d declared: “I’m terribly optimistic and I believe I have something to offer.”

After early wealth, Stoner’s acumen and personality build an empire

Born an only child in Des Moines to an upper-crust father and an actress mother, Stoner had an innate intelligence and a preternatural ability to hold people’s attention, says Mary Riche, friend to the family since 1975, when she and Stoner’s wife, Kitty, joined the Commission on the Status of Women.

“His ability to be in front of an audience was unmatched,” she says. “He had this very easygoing style and this twinkle in his eye. He made it look easy.”

A self-made millionaire, T.I. Stoner started whitewashing houses after school at just 13, the humble beginnings of what would become the family’s billboard and outdoor advertising firm.

Despite the family’s wealth, Stoner’s father wanted him to “know the real meaning of work,” Stoner told the Register in 1984.

“So while the rest of the kids were out playing football, I was building signs,” he said. “I could dig post holes, I could post signs, and I could do illumination.”

Stoner attended the Cranbrook School, a boarding school in Michigan, where, according to his obituary, “he built his first crystal radio set.” He then studied economics at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and headed straight for the family business CEO chair.

In the 1960s, he abandoned billboards for radio, founding Stoner Broadcasting System, and invested in a real estate development firm. By 1979, his net worth was nearly $9 million, according to records filed in the Senate race.

“He’s a very agile guy mentally and he’s very careful in thinking things through,” friend Buz Brenton said in a Register profile. “There’s been a lot of talk about him being born with a silver spoon in his mouth and it’s true he did inherit some wealth.”

“But he’s turned that over two or three times, got out of one business and into another and turned that into a lucrative business. And he’s structured it all so he can do other things.”

Like, for example, run for office.

A hands-on campaign manager, Tom Stoner helps Bob Ray win — in the face of Watergate

Similar to Ray, his mentor, Stoner was a moderate Republican.

“And that fit Iowa like a good work glove at the time,” Offenburger says. “That was the heart and soul of the Republican party that had ruled Iowa since the Civil War. They had evolved over time, but they were still a progressive group of moderates that did well by the state.”

Stoner had been a member of the young Republicans after college, but stayed out of the fray until 1972, when he managed Ray’s re-election and followed that up quickly by playing the same role in the 1974 campaign. (Iowa governors had two-year terms until 1974.)

“I remember some of the stories when the governor was mulling whether to run again and he asked, ‘Can you promise it will be fun?'’’ says David Oman, a Republican strategist who was a first-time staffer back then. “Tom promised that it would be, and he was the one that made it fun.”

Within a matter of days after joining the Ray campaign as a 22-year-old, Oman says the team gelled specifically because Tom and Kitty knew how to make them feel like they each were important and each deserved a seat at the table.

“Having been in business, he knew how to organize and how to make something run like a clock,” Oman said. Stoner went on the road with his staffers, visiting chairs of the larger counties, which was uncommon for the time, Oman says, but he wanted to put eyes and ears on all parts of the organization.

And with Watergate taking over every inch of newsprint, this was not an easy year to be a Republican. That November, many incumbent Republican governors lost re-election campaigns, including a majority in the Midwest.

But, with Stoner’s help, Ray was re-elected.

After that, Oman says, Stoner got the bug himself. He was already so much like Ray — hard-working, high energy, rich sense of humor, able to laugh, great on TV — that he figured he'd try his hand at being on the ticket instead of just behind it.

“Tom was forever young," Oman says. "He was so energetic and so fun-loving that it was a complete joy to work with him."

A few years after Stoner’s loss, Oman went on a trip out East and visited Stoner in Annapolis. Stoner told him that he’d gone to D.C. soon after that election and invited Grassley out to lunch to say that anything that had happened in the campaign, well, that was ancient history.

“That was Tom: ‘I ran, I didn’t make it, but that was yesterday,’" Oman says. “But today is a new day.”

Picking up croquet at 70: Stoner was a ‘lifelong learner’

Soon after his loss to Grassley, Stoner relocated to Annapolis, a move he said put him closer to the Federal Communications Commission and to the ocean, where he could participate in his beloved pastime, sailing.

He also opened the Conflict Clinic, a gathering of “some of the nation’s finest minds,” according to a Register story, that was tasked with solving big issues and disputes before they blossomed into catastrophes.

In the same vein, he founded “Worldtalk” in 1988, the first live radio call-in program directly linking citizens of the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. And nearly a decade after that, he and Kitty founded Nature Sacred.

Stoner was a patron of art and music, Riche says, hosting an exhibit that bolstered the Stanley Museum of Art’s national reputation and funding the Stoner Theater inside the Civic Center.

In a 2012 Baltimore Sun article, Stoner and Kitty shared how they’d gone on a worldwide hunt to collect 40 pieces from the 40 sculptors that best represent the 20th century. But not only did they collect, they studied: reading biographies and memoirs of each of the artists, visiting galleries, birthplaces, even graves.

And at age 70, Stoner decided to learn both piano and croquet.

“He really was a lifelong learner,” Riche says. “That’s what I will remember; that he never, ever, ever stopped trying new things and learning new things.

“He was amazing in so many ways, but in that sense, he was truly inspiring.”

Stoner is survived by his wife, Kitty; four children, five grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren.

Courtney Crowder, the Register's Iowa Columnist, traverses the state's 99 counties telling Iowans' stories. Reach her at ccrowder@dmreg.com or 515-284-8360.

Next: Crowder explores the work of Nature Sacred and its mission to install 100 green spaces in the next few years — including some in Des Moines. Look for her story this week online and in the Des Moines Sunday Register.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Tom Stoner: Broadcaster, businessman, Republican and philanthropist has died