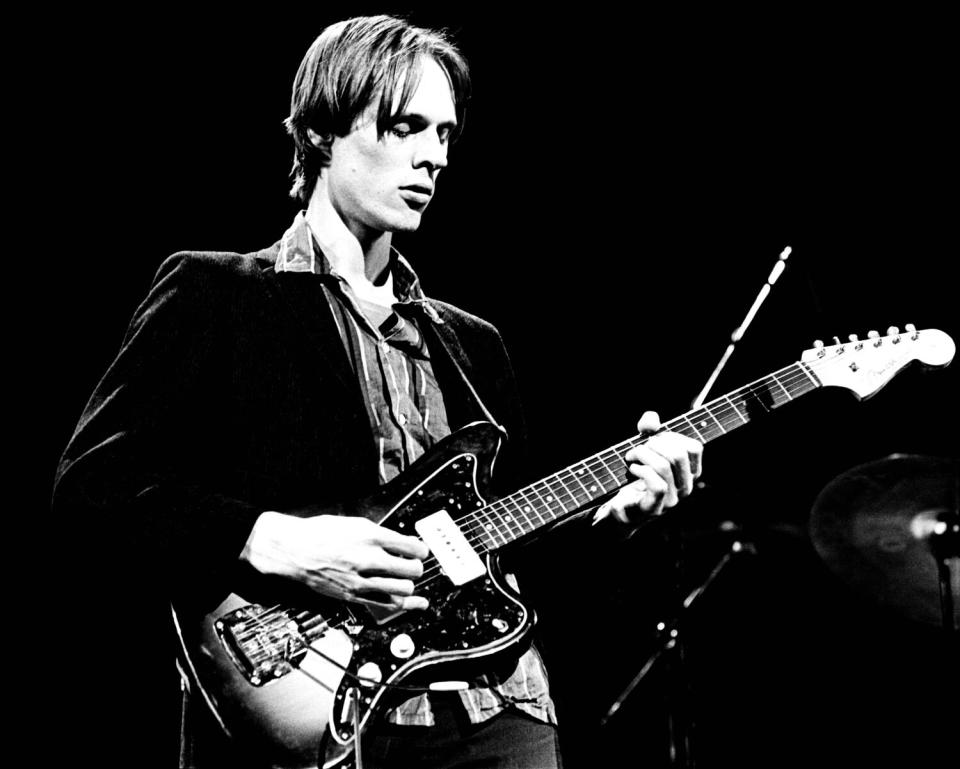

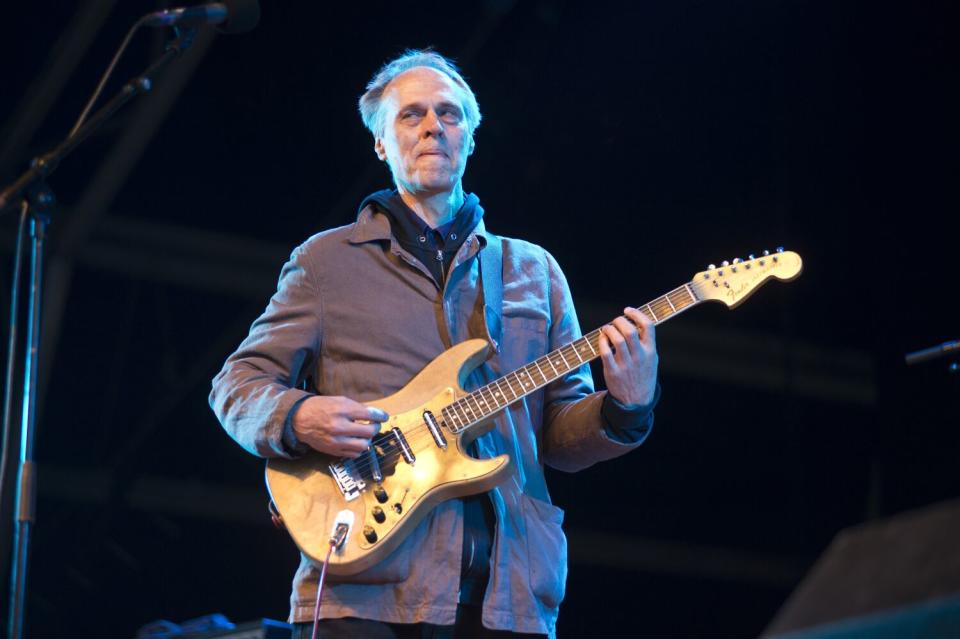

Tom Verlaine, singer and guitarist for seminal art-punk band Television, dies at 73

Tom Verlaine, the singer and guitarist who fronted the singular, ambitious and oblique New York band Television, with whom he made two of rock’s most acclaimed albums, died Saturday in Manhattan. He was 73.

Verlaine’s death was confirmed to The Times by his former manager, John Telfer, who stated that it followed “a brief illness.”

Jimmy Rip, a friend who played with Verlaine for decades, wrote on Instagram, “At the end, he was surrounded by love and passed peacefully with the hands of myself and four more of his nearest and dearest friends on him.

“The personal loss, for me, is absolutely devastating. The loss, to the world, of this most innovative, imitated and iconic artist is incalculable.”

Although Television first attracted attention at the New York punk rock club CBGB, Verlaine wasn’t a fan of punk, which he described as “just amped-up bubblegum with angrier lyrics.” Among other things, punk bands eschewed solos; Verlaine and fellow guitarist Richard Lloyd did not. In 2012, Spin magazine placed Verlaine and Lloyd seventh on a list of the 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time, likening their soloing to that of the Grateful Dead; Mojo magazine ranked Verlaine 34th on a similar list (one place ahead of Jerry Garcia), and Rolling Stone slotted him at 90.

The first two Television albums — “Marquee Moon,” released in 1977, and “Adventure,” a year later — were enough to cement the band’s legend. But the records didn’t sell, and the band broke up, reuniting for a third album, “Television,” in 1992 before disappearing again. They toured sporadically, even after Lloyd left in 2007, having grown frustrated at Verlaine’s unwillingness to record new music.

Television introduced ideas that hung around rock for decades. Subsequent generations of musicians seemed to base their styles on one song or even part of one; the bridge to the stupendous 10-minute track “Marquee Moon” anticipates much of Sonic Youth’s output, and R.E.M.’s first decade seemed to spring from the cascading arpeggios in “Days,” from “Adventure.”

Verlaine was passionate about harmonically complex music, especially jazz saxophonists John Coltrane and Albert Ayler, classical composers Henryk Gorecki and Krzysztof Penderecki and film composers Bernard Herrmann and Henry Mancini. He was also a sophisticated fan of literature, including the French Symbolists of the late 1800s, including the poet Paul Verlaine, to whom he paid tribute when inventing a pseudonym.

Thomas Miller was born Dec. 13, 1949, and grew up in Wilmington, Del. He learned piano and sax, then switched to guitar. His parents, Victor and Lillian Miller, sent him to boarding school, where he met a troublemaker named Richard Meyers. The two devised a plan to run away to Florida, and with $50 between them, they set out like teen-rebel versions of Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer, mostly hitchhiking.

The pair got as far as Alabama, where they slept rough in a field one night and started a fire to keep warm. When they began throwing burning sticks around the field, it caught fire, unsurprisingly, and they were arrested.

Verlaine finished high school and endured a year of college before moving to New York in late 1968. Meyers, who renamed himself Richard Hell, visited Verlaine, and they hung around dank New York clubs like Max’s Kansas City and the Mercer Arts Center, where they saw the New York Dolls.

“We were inseparable,” Hell said in the punk rock oral history “Please Kill Me.”

Both worked at a bookstore called Cinemabilia, managed by Terry Ork, an Andy Warhol assistant who lived in a capacious Chinatown loft. Verlaine had been playing acoustic guitar at hootenanny nights around the city, and Hell prodded him to start a rock band.

“I didn’t see anybody in New York then who was doing anything,” Verlaine said. “It was all glamour — all visuals.”

Verlaine taught Hell, a novice, to play bass, and with drummer Billy Ficca, whom Verlaine knew from Delaware, they formed a trio called the Neon Boys, which recorded two songs that weren’t released until 1980. After they broke up, Ork introduced Verlaine to Lloyd, completing the original lineup of Television.

They played their first gig at the Town House Theater in March 1974, the same year Verlaine played guitar on Patti Smith’s first single, “Hey Joe.” (He played guitar the next year on her debut album, “Horses,” as well, and the two became a couple.)

While looking for a place where they could gig regularly, Verlaine and Lloyd spotted a dive bar on the Bowery, above a flophouse unpersuasively called the Palace. The club’s name was CBGB, which stood for country, bluegrass and blues, and Verlaine and Lloyd lied to owner Hilly Kristal, claiming that was the type of music they played, in order to get a foot in the door. Soon, Smith, Talking Heads, Blondie and Ramones were playing there too. The Bowery was never the same.

At Hell’s urging, Television adopted short hair, a sullen demeanor (which may have come naturally) and unkempt, sometimes ripped clothes.

“This was a severe aesthetic,” the British critic Jon Savage later wrote, which “spelt danger and refusal, just as the torn T-shirt spoke of sexuality and violence.”

“There was something very, very modern” about Television, filmmaker Mary Harron once recalled, “something very liberating about that negativity. It was so hard and cold.”

Hell and Verlaine shared lead vocals, but the latter didn’t like the competition and felt the former’s modest bass skills were holding the band back. They sometimes even fought onstage. So Verlaine forced Hell out and brought in Fred Smith, who’d been playing with Blondie. Ork gave the band money for amps and studio time, and they recorded a 45, “Little Johnny Jewel,” a seven-minute song split into two sides.

Verlaine was tall and gaunt, with “the most beautiful neck in rock ‘n’ roll,” Patti Smith once opined. His unusual, strained voice guaranteed that Television would never get significant airplay on commercial radio. Singer Adele Bertei described it as “all awkward and angular, like the voice of puberty cracking,” and Lloyd likened it to the sound of a goat with its throat slit.

Record labels began shopping frantically at CBGB, and Television signed with Elektra Records for their first two albums, which were not celebrated in their day as much as they were subsequently. But the New York Times praised “Marquee Moon” for the way it “builds mystical, compelling edifices of sound from clanging electric-guitar basics.” (“Marquee Moon” routinely places high on lists of the greatest rock albums.)

Even their producers were sometimes baffled by this strange music. Andy Johns, who produced the Rolling Stones in addition to Television’s debut, once asked Verlaine, “What is this? Is this New York subway music?”

At the same time, there was a grand, sprawling aspect to their concerts. A live version of Marquee Moon" could stretch well past the 20-minute mark.

They were the opening act on Peter Gabriel’s first solo tour and were met with howls of “You suck!” When Verlaine announced he wanted to leave the group, Lloyd said he wanted to do the same. They broke up on a full moon in 1978.

“Moby Grape broke up on a full moon, so we wanted to, too,” Verlaine said.

Bands that loved Television didn’t try to hide their devotion. R.E.M. and Joe Jackson covered “See No Evil,” Echo & the Bunnymen played “Friction,” Siouxsie & the Banshees cut “Little Johnny Jewel,” and the Kronos Quartet took on “Marquee Moon.” The Canadian indie-rock band Alvvays titled a song on its latest album “Tom Verlaine.”

When Television reunited in 1992, grunge and weird guitar rock were ascendant. Music had caught up to them, but their reunion album, while excellent, was more about flickers than explosions. There weren’t any songs longer than five minutes. The solos were brief. Even Verlaine’s singing was more sedate.

Verlaine’s fussiness about music was legendary. In 1980, when David Bowie was recording the “Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps)” album, he covered “Kingdom Come,” which Verlaine had recorded on his solo debut a year earlier. Bowie and producer Tony Visconti asked Verlaine to play guitar on the track, but according to Visconti’s autobiography, Verlaine spent hours trying different guitar amps, looking for the right sound. Bowie and Visconti went to lunch, watched some afternoon TV and left the studio at 7 p.m., while Verlaine was still fiddling with amps.

“I don’t think we ever used a note of his playing, if we even recorded him,” Visconti wrote. “We never saw him after that day.”

Few people did. Fans traded tales of spotting Verlaine rummaging through the aisles at Strand Book Store. In addition to Television shows and infrequent solo albums, he played on albums by Smashing Pumpkins guitarist James Iha, Japanese guitarist Yasushi Ide, New York alternative rock band Luna, Cars singer Ric Ocasek and folk-punk band Violent Femmes, among others.

An early newspaper profile described Verlaine as “proud, a bit defensive and very much a loner.” Even as Television’s reputation grew and grew, their greatness hailed by U2 and many other bands, Verlaine stayed in the shadows. He released the last of his nine solo albums in 2006. That year, when a reporter asked him to describe his career, Verlaine said slyly, “Struggling not to have a professional career.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.