The Tony Awards Are Postponed. How Will George Floyd and Coronavirus Impact Theater’s Rebirth?

Tonight should have been the Tony Awards: a night of Patti LuPone, more Patti LuPone, impassioned speeches about theater kids pursuing their dreams...and even more Patti LuPone. But Broadway has been shut since March 12, and with it the postponement of those shows (and cancellation of a few others) that would have qualified for them. Indeed, this year the Awards feel a faraway shadow—and not just because there is no Broadway to fuel a ceremony right now.

The death of George Floyd and subsequent protests and debates about racism and change have led Broadway and the wider world of theater—like many individuals and institutions—to necessarily question itself, not for the first time, about the need for urgent change.

Yet again, theater confronts a set of urgent questions—about the disproportionately low number of works by playwrights of color being commissioned, the nature of the works being staged, the composition of the audiences watching those works, and the lack of diversity on stage and off.

‘Incredibly Powerful’: Eleventh Day of George Floyd Protests Is the Biggest Yet

Of the many heartfelt Floyd-related statements from shows including Hadestown, Company, and What The Constitution Means to Me, one particularly stood out—from Slave Play, which donated $10,000 to the National Bailout Fund, and challenged other shows to do the same. Others posted statements and links to resources. Black members of the Broadway community—including from the casts of Tina Turner: The Musical and Ain’t Too Proud—marched in Harlem.

The Broadway League has said it is “committed to providing a safe space where these stories can be shared. We strive to open doors, hearts and minds that will lead to understanding, action and change.”

The big question: Will there be a translation of fine words to action by theaters and powerful producers? One emphatic sign in Manhattan in recent days came from the Public Theater, the New York Theatre Workshop, the Atlantic Theater, and Playwrights Horizons who have issued not just statements, but opened their lobbies to demonstrators.

Because of the coronavirus pandemic and the continued mystery about when Broadway and theater will return to life—Broadway League chief Charlotte St. Martin recently posited January 2021 to The Daily Beast—the theatrical world not only has the time and space to confront these questions, but perhaps also to come up with actual solutions.

Away from nights like the Tony Awards, theater is not just boldface names and bright lights. Far from it. Most of Broadway’s almost 100,000 workers are far from famous, and they work—like everyone else—to pay their bills, and ensure their own and their loved ones’ welfare.

The shutdown of Broadway, indeed American theater far from Broadway, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, has been life-altering for those who make their livings from theater, as they struggle to live while waiting for theater to return. This will likely be one of their final sectors to come back to life, which amounts to almost a year out of work, with dwindling funds and possibly soon-to-evaporate healthcare.

Broadway League President Hopes for January Reopening—with Full Theaters and Masks

Below, a range of people—from musicians to producers to electricians—talk about losing loved ones to COVID-19, absorbing the impact of George Floyd’s death, not being able to do the jobs they love, financial pressures, and what they think it will take (a vaccine, new kinds of seating and theater geography) to get audiences, performers, and stage crews back into theaters.

“The last 3 months have been emotionally challenging for me as a member of the African-American community, and as a member of the theater community,” Victoria Velazquez, CEO of ZAVE Media, and co-founder of Women of Color on Broadway, told The Daily Beast.

“The COVID-19 pandemic brought a lot of stress to the theater industry, and for a while, Women of Color on Broadway was focused on configuring ways to help essential workers who are overworked as well as the hundreds of theater professionals who have lost their jobs. Then, George Floyd was murdered by police officials, and we decided to get involved in hopes justice is served not only for Floyd, but for Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery as well.”

“As a member of the two communities, the last few months have opened my eyes on the importance of serving our community. I feel a lot of people, myself included, always wanted to get involved with social work, but didn't know how. I’ve experienced a realization that no act is too small. Signing a petition, sharing accurate news, donating, protesting, it all has a large impact.”

Victoria Velazquez

Last year, The Daily Beast spoke to a number of women of color working in theater, who talked about their experiences of racism on stage and off. In the same article, we wrote about the studies which revealed the statistical disadvantages creators and performers of color endure working in theater.

Women of Color on Broadway said that between 2008 and 2015 people of color represented less than 25 percent of the theater industry. The union Actors’ Equity’s first study of diversity, published in 2017, showed that women and members of color have fewer work opportunities, and often draw lower salaries when they do find work.

Caucasians made up a majority of all onstage contracts—principal in a play (65 percent of contracts), principal in a musical (66 percent of contracts), and chorus (57 percent of contracts). Caucasians were generally hired with higher contractual salaries. African-American members reported salaries 10 percent lower than the average in principal in a play roles, for example.

Seventy-seven percent of stage manager contracts on the Broadway and production tours went to Caucasians. Over three years there were only six contracts given to African-American members.

The Asian American Performers Action Coalition’s annual study of Ethnic Representation on New York City stages for the 2016–17 season revealed, as Playbill reported in March 2019, that 95 percent of all plays and musicals were both written and directed by Caucasian artists.

The situation isn’t entirely bleak, as the success in recent times of black playwrights including the Pulitzer-winning Michael R. Jackson, Jeremy O. Harris (Slave Play), Jackie Sibblies Drury (Fairview), and Donja R. Love (Sugar in our Wounds) has shown. The question is whether theaters will provide more space and consistency in supporting both the work of playwrights of color, and people of color working in theater more generally.

In the wake of Floyd’s death, Velazquez has “not heard a lot from producers. However, I have seen a number of Broadway companies, and even writers contribute to organizations such as the The Actors Fund and Color of Change. As someone who is a part of a theatrical entity or organization, I am very proud of businesses such as Open Jar Studios and Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS for the actions they’ve taken to help essential workers and victims of police brutality. I want to encourage everyone to do the same.”

The influential Broadway and off-Broadway producer Daryl Roth told The Daily Beast: “I think it’s our responsibility to do better about making sure that voices are heard, and that black playwrights and stories are told and represented. We need to do better.”

Roth said she was proud to have produced Anna Deavere Smith’s Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992, and Notes From the Field (presently on HBO). “It’s valuable to bring such work forward, but we have to be conscious of making sure not only her plays but other plays are put at the top of the line right now. We have to pay our respects, and do the right thing. There are some wonderful playwrights not as equally represented on stage. That’s our responsibility.”

The impact of COVID-19 has been felt keenly in the theater community, not simply measured by closed theaters. There has been much coverage of Nick Cordero’s ongoing battle with the illness, while The Daily Beast reported on Broadway designer Edward Pierce’s history-making struggle to recovery.

For Jason Marin, a lighting programmer for theater, television, and live events, the last eleven weeks have been incredibly painful. Both his in-laws, Erica and Ira, who lived in northern New Jersey, died from COVID-19.

They began to exhibit flu-like symptoms in the last week of March. “That lasted for perhaps three days before they were sick enough to call for an ambulance,” Marin told The Daily Beast. “Both of my in-laws were confirmed as having Covid-19. It became clear that the hospital staff was completely overwhelmed. Doctors with no direct knowledge of their cases were making calls to my wife (Hillary Cohen) to update her based on their charts, since no one could be spared to make those calls.

“My in-laws only got to spend one night in the same hospital room, though my wife was fortunately able to speak to her mother several times. My father-in-law was taken to the ICU, where he was put on a ventilator—he died after a cardiac arrest, a successful resuscitation, and another cardiac arrest. My mother-in-law never saw him again.”

She, in turn, “had a few good days in a row where she got slightly better each day, and was able to talk to my wife for about two minutes each night, Marin said. “She just didn't have the lung capacity for any more. Then, her pulse oxygen crashed, she was taken to the ICU, intubated, and put on a ventilator. My wife didn’t know she'd already spoken to her mother for the last time—her mother improved on the ventilator and was eventually taken off, but died the day following.”

After that, “anxiety turned into depression,” said Marin, also works as a lighting designer and administrator. His wife went back to work immediately. “She didn't know what else to do. She had to handle all aspects of the burials herself, and do it remotely.”

Marin’s wife asked her twin brother Evan to come stay at their home in Morningside Heights, “rolling the dice that we wouldn’t get him sick and vice versa. Having him with us has been a help for us both.” While she works, Marin— whose most recent Broadway credit is Light Board Operator for Harry Connick, Jr.: A Celebration of Cole Porter—has spent his time on training and seminars, cooking, checking in on his mother and friends by phone and FaceTime, and talking with all of his contacts throughout the business.

Paul Masse, a Broadway musician since 2001, and conductor on shows including The Scottsboro Boys, Porgy and Bess, and Holler If Ya Hear Me, said he was, “like most in the business, feeling a bit helpless, alternating between hopeful and despairing.

“We are all experiencing so many different layers of grief for the loss of so many different things: of course foremost our family and/or friends lost directly to COVID-19, or to other issues during this time; but we've also largely lost our livelihoods, our outlet for our passions, our daily camaraderie and interactions. I have not personally lost anyone close to me, thankfully, due directly to COVID-19. My life has been upended certainly, but we will sort it out somehow.”

Right now, Masse is thinking much more about “how to use this time and this ‘restart’ in a way to effect change. In commercial theater, we often forget about the importance of what we do, and the lives it can impact. After all of the news (following on from the death of George Floyd), I am reflecting on the ways in which I can harness my drive for arts and music and theater toward helping the fight for equality and an end to racist behaviors being an acceptable thing in our world.”

“Non-profits and commercial producers have to be more diligent about producing those plays and representing the voices of playwrights of color,” said Daryl Roth. “We must also be mindful about employing in a fair and equitable way, hiring directors, hiring scenic designers, hiring people of color in all areas. It has to be a conscious effort until it becomes the natural thing we are all doing.

“I think all of us should do what we can to make it a better and more fair situation for everybody. I don’t think we have done as much as we can, and this is an awakening for everybody in all fields. We should be mindful when we are hiring, mindful when we are making selections of what we produce, and mindful we are representing all voices.”

“The only time we see each other is during a Zoom conference”

Theater workers are negotiating a range of difficult situations, financially and emotionally. John Curvan, assistant house electrician at Broadway’s Gershwin Theatre, home of Wicked, has a son in college and another in high school. Like many Broadway workers, he received two weeks’ severance and has since been able to successfully apply for unemployment.

“I have been a stage-hand since I was 16,” said Curvan. “I’ve been doing this for three decades, so I’m a bit further along than some. I always knew a freelancer needed cash reserves, and I have had a steady paycheck working on Wicked for 16 years, which is quite unusual in the entertainment industry.”

Victoria Velazquez said there had been a lot of educational and theatrical institutions and non-profit organizations like WOCoB that have been financially affected as a result of the COVID-19 national shutdown.

“As a newly established non-profit organization who uplifts women of color in musical theater, most of our tentative projects originally took place in a live setting, with a full cast,” Velazquez said. “We had to make a very difficult decision to cancel or postpone our events until further notice, as well as cut-down on WOCoB staff’s salaries for the rest of the year.”

All Women of Color on Broadway members had been economically and emotionally affected by COVID-19, Velazquez said. “Some of us are either related to, or live with essential workers. The WOCoB Team is very close-knit, and we’ve prioritized conversations surrounding our mental and emotional health during these tough times to help us get by.

“We’ve all been working from home since March, and the only time we see each other is during a Zoom conference. Despite the ways the past three months have affected us individually, I am so proud of my team for staying focused on our mission during the quarantine. The past few months have also inspired us to explore ways we can get more involved with social causes. I’m looking to share what we have in store in the near future.”

Daryl Roth said she did not think theater would open up next spring, and only when appropriate safety measures were in place. “Speaking for myself as a grandma who loves to bring her grandchildren to the theater, I don’t think I’d be comfortable with that and won’t be for some time.” Perhaps, she thinks, some off-Broadway, or local theaters, could open before then.

At the theater which bears Roth’s name near Union Square in New York City, Roth and her colleagues are already planning to use fewer, socially distanced seats in its main theater for its first post-lockdown productions; the smaller theater she intends to give over to practitioners filming online content.

Roth is “optimistic” about theater’s return. But, she said, “I don’t know how Broadway is going to work. I know you can’t currently sell a third of the house and expect it to work.”

The problem for Broadway was its heavy dependence on tourism, Roth said. Broadway would be negatively impacted, she said, “until it is safe to travel, flying, driving, taking the train. It’s devastating, especially when you think about all the surrounding businesses—restaurants, bars, hotels—who depend on Broadway for their business.”

“As someone who has done more than my share of flop shows on Broadway, I have been unemployed many times before, but the overall idea that it is completely indefinite, and there are no prospects has been quite stressful,” said Paul Masse. “I’m OK for this month, but I have no idea what I will do if another addition to unemployment isn't passed in Congress. I have been frustrated at the way in which people elsewhere don't seem to understand that $600 a week in New York City is far from a lot of money. I also—along with most of the musician’s union membership—am scheduled to lose my health insurance at the end of August.”

When this reporter asked Nathan Gehan, president of Fifth Estate Entertainment, a Broadway and national touring producing and general management firm, what the last few weeks had been like he said, bluntly: “It’s been about closing shows, and strategizing with other productions about when they might come back.”

Gehan’s firm oversees 31 shows. One Broadway show which he did not name had still not canceled the possibility of opening in the fall; the others have moved to date tbd, 2021.

“The productions really want optimism. Most are feeling a 2021 return. If anything returned in the Fall, people want to see a tremendous amount of implementations around social distancing and other protections to make sure they are safe. If there is a second wave, everything is off the table. People’s health is the first priority.”

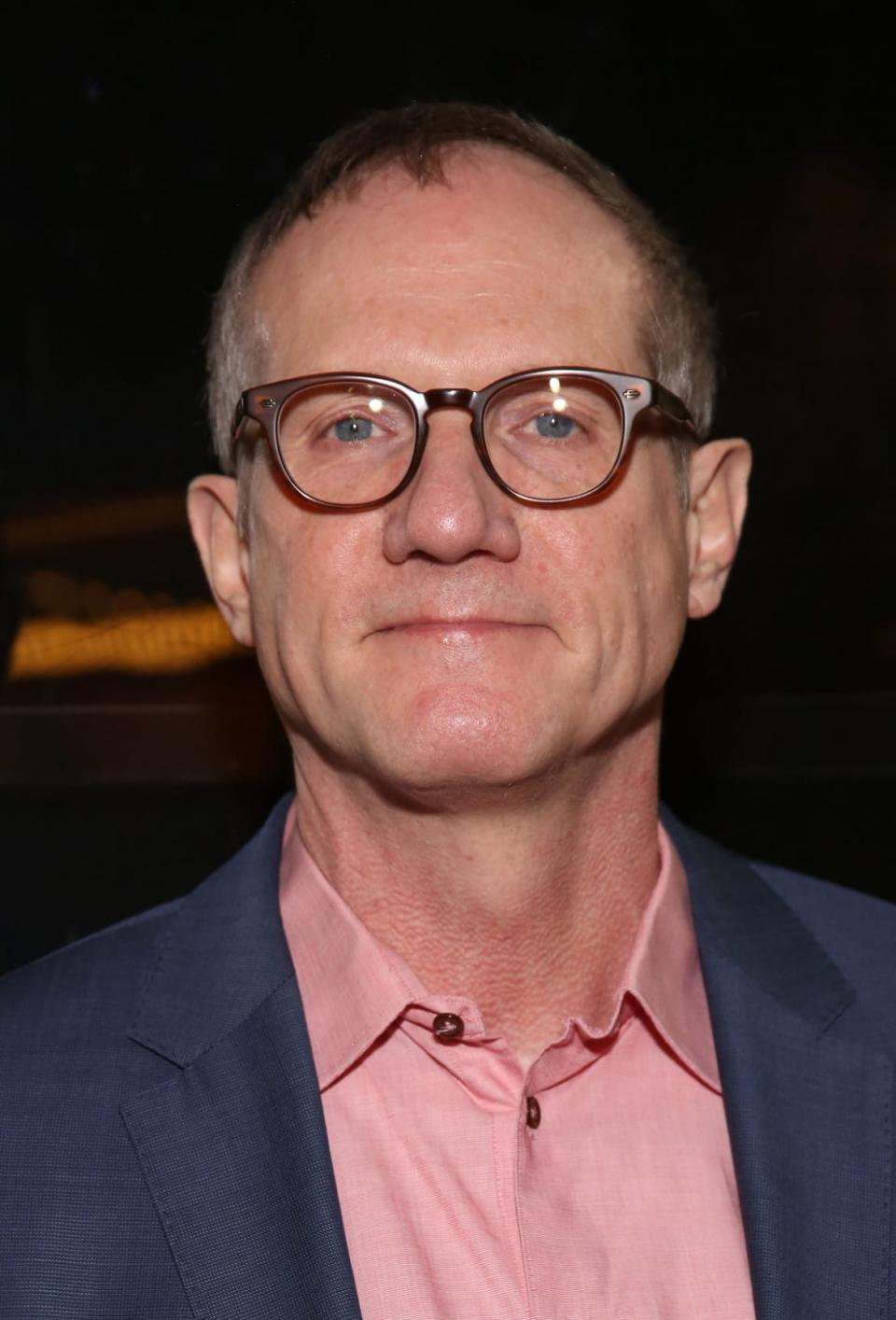

Mark Brokaw

“The rehearsal room is frozen in amber at the moment,” said Mark Brokaw, director of How I Learned to Drive (starring Mary-Louise Parker and David Morse). The company had been in their third week of rehearsal when the lockdown occurred. It has been 23 years since the play premiered off-Broadway, and, said Brokaw, it had taken that long to reunite everybody for this production.

“Of course we’re all incredibly disappointed, but we also realize we’re all healthy. That’s the most important thing right now,” said Brokaw. Producers Manhattan Theatre Club remained committed to the production: “The only question is when. This is a life-affirming story of survival and hearing. It’s the exactly the type of story people want to be part of.”

Theater, said Brokaw, would only begin when people feel safe to congregate in large numbers and have close contact again.

“Theater is a contact art. You can’t make it without others, and most importantly an audience.” A vaccine would be the most effective reassurance, he added.

Brokaw is looking forward to reimagining how productions are staged. “I do think it’s a real chance to examine how we’re doing things and how we might do them better. It may lead to more focus returning to the actor and text, and less to the bells and whistles. A greater reliance on the imagination on both sides of the footlights cd be a very positive result.”

In the field of music, “there is definitely a divide in financial security between those who are musicians on a long-running hit show, or who are in tenured classical orchestras, but that has always been the case and it makes sense that it is,” said Masse. “I think the real commonality will turn out to be the health insurance issue. Our health fund has been historically tenuous even in good times, so we are all waiting to hear what will happen if Congress doesn't approve a COBRA subsidy, or some other kind of health insurance subsidy doesn't come about. It is the height of irony for millions to lose their health insurance in the name of public health.”

Laura Penn, Executive Director of the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society (SDC), said, “The effect of coronavirus on the ecosystem of American theater is devastating, and devastating for directors who are lucky to make $25,000 a year.” Yes, there are star directors, she said. but even they work project to project. The “minimum weekly guarantees” members can earn is $899 for a choreographer; $1,469 for the director of a musical, and $1,073 for the director of a play.

Laura Penn

Penn said she had been hearing “what everyone else is hearing—which is something different every day,” in terms of what will reopen first and how it will reopen. The SDC’s members, she said, were concerned about healthcare (some runs out on Sept. 1; “if you’re lucky” it goes to March 1) and living expenses. Some, like Penn herself, have a child headed to college.

If these concerns are shared by all workers, others are more specific, such as directors and choreographers acting as pastoral leaders for the productions they lead; Penn calls this the “invisible work” that is hard to classify and quantify, as the amount of emotional support they are offering to members varies so wildly—particularly as actors do not know when they are going to work again.

“If our business is shut down past September, my family will start getting squeezed”

Just as it has for so many, time over the last few months has stretched strangely for theater workers in terms of living in a fraught, unpredictable present while trying to get some kind of grip on an unknowable future.

Jason Marin recalled March 12, the day theater was shut down. “Looking back at that week, it’s clear we really had no idea what was happening, and I wish we’d had better communication from our government leaders,” said Marin. “On that Monday, I was getting concerned about the number of cancellations we were seeing in private events, but it still seemed like something that would stop.

“On Tuesday, my wife and I went to see my mother, which could have put her in mortal danger—we just didn’t realize it at the time. On Wednesday I had an equipment demo, and was still talking to vendors about upcoming shows. When the shutdown happened on that Thursday, it seemed to come out of nowhere because we were getting inconsistent or no information from the different levels of government.”

As of that Friday, it seemed like the shutdown might last a few weeks, said Marin. “Over the course of that weekend, the 14th and 15th, my wife and I realized we were going to need to start sheltering in place, even though the official order hadn’t come yet. Fortunately, she was able to start working remotely on the 16th, and has been doing so ever since. I had anxiety about work, she had anxiety about raising money—she is the managing director for a non-profit theater company.”

Marin has spoken to manufacturer representatives, designers, rental agents, producers, generator suppliers, and venue directors, among others. “If there’s good news, it's that no one seems to misunderstand the dangers and challenges we face. They don’t want to start back up too early and then have to shut down again—or worse, not shut down again, and watch everyone get sick.”

Marin grew up in poverty, “so I try to always have several months’ expenses on hand just in case. With that, unemployment, an accumulated vacation time payout, and 3 months’ mortgage forbearance, we are not in a bad place financially. If our business is shut down past September, my family will start getting squeezed.”

The real difficulty, said Marin, “is keeping focus for any stretch of time. It's difficult to have no control over our situation and no idea when this will end. I managed to complete a 30-hour certification course earlier in the shutdown, but staying focused seems to be getting harder. There are books I'd like to read and educational opportunities I'd like to take advantage of, but they seem impenetrable in a way they never have before in my life.”

For Marin, “it seems out of line to talk about my stress about work with my wife or her brother; they lost both of their parents! I can't expect them to sympathize with what is going to be a temporary problem. As much as I miss their parents too, my pain is only a fraction of theirs.”

Money will be an issue when it comes to financing shows, Mark Brokaw thought, so making do with less would become a necessity. As Broadway productions have increased in scale in recent years, scaling back would be welcome. “For me, what theater does is special: an actor on one side of the footlights and the audience on the other, and the text traveling between the two. It will challenge us to do the work more imaginatively than ever before.”

“It’s sad and frightening to be involved in an emergency, for all of us. But at the same time it has given directors the opportunity to think about what we are doing and how to do it better. Instead of sitting around and saying ‘Woe is us,’ we’re thinking of how to turn this negative into a positive.”

Daryl Roth wondered if she would soon see the drafts of plays framed and written very directly in the wake of George Floyd’s killing, or if theaters would commission more work just generally from playwrights of color. “We have to listen and we have to learn, and I think we have to be responsible, and be aware of what we have to do to lead by example,” she said.

Citing the success and impact of Jeremy O. Harris’ Slave Play, Roth said it was imperative to amplify his and other playwrights of color. “Theater has to do better. Everybody has to do better—corporations, businesses. Everybody must make an effort to ensure equality and human rights for everybody.”

“Professionally, I'm optimistic,” said Victoria Velazquez of Women of Color on Broadway. “I am very well aware of the times we're living in, but I also believe that things will turn around for the better as the pandemic slows down. Women of Color on Broadway is a very adaptable company with a super creative team.

“We will continue to serve our mission regardless of what happens in the future. I'm also professionally optimistic because I feel unions and producers are being pressured by the actors to take more action, which is something I completely support.”

Paul Masse

Paul Masse said he was grateful to all of the organizations who have stepped up with grants and other assistance, and certain non-profits who have made it possible to honor contracts when others have not.

“It will be remembered and is not taken for granted. Any organization who has their eye on any type of future will recognize that doing everything you possibly can for your artists now will pay dividends for years to come,” he said.

Masse had hoped “there would perhaps be a bit more obligation felt on the part of producers with enormous hits to at the very least ensure that everyone who works in your theater would have health insurance until we can go back to work—it only makes returning that much easier and healthier.”

Brokaw does not know when theater will return, and in the meantime he and his colleagues are figuring out what work they could do to tide themselves over, like coaching executives, for example. He remains optimistic that those productions on pause will happen, and that “there will be a real hunger” to see them.

“I will say we know how much demand there is for live performance—on Broadway, in concert halls, in arenas, throughout the city,” said Jason Marin. “I'm sure the response to Hamilton on Disney+ will be tremendous. The key will be: when will people feel comfortable traveling and viewing performance in person, both health-wise and financially?”

Masse said he was “concerned by the rhetoric of some people in leadership positions” in theater when it came to addressing the future of musicians.

“Musicians on Broadway are routinely forgotten and can often be the last on the minds of many. The insinuation that ‘not every show needs an orchestra’ is a dangerous one…In an industry that has been trying, often successfully, to chip away at the size and quality of orchestras on Broadway, this was sort of a dog whistle for many of my colleagues.”

Masse said he and other musicians intend to be “included in conversations, and that our voices are heard” alongside their performer colleagues, their unions, and the front-of-house unions and guilds.

The musicians’ union, Local 802, has been working with the other unions closely, from what Masse has been told. “I am concerned about our health fund the most, and there has been very little transparency on that. The health insurance field is incredibly complicated, but the IRS and the Department of Labor have made several emergency changes to things like COBRA eligibilities and ERISA or ACA-compliance and I just hope those things are effective.”

“We all need to keep our health insurance—no matter how that is achieved, whether it is a COBRA subsidy, employers stepping up, or the unions sorting out whatever they need,” said Masse.

Some Broadway shows will move out of their theaters as soon as it’s safe to have crews working again, said Marin. “I’m sure we will see empty theaters for a while; it can take a long time to put a show together.”

“I do suspect we will see some music acts like the In Residence series which ran at the Lunt-Fontanne or musical revues like Kristin Chenoweth: For The Girls which ran at the Nederlander—shows that can be put together relatively quickly and without a huge amount of capitalization required. Shows like this can keep theaters running while big productions with long lead times can be readied.”

Nathan Gehan anticipates the opening of some regional tours before Broadway, “but if there are any pandemic spikes in the middle of the country, all bets are off.”

Gehan does not see theaters being reconceived with social distancing in mind; the present cost structures of Broadway does not make it viable. Gehan has managed to keep his employees full salaried until July 1 because of a PPP loan; after that, he does not know. “We may take a break or have to close for a time,” said Gehan.

Laura Penn said, “As best as I can grasp, everyone wants to open and stay open,” said Penn. “We don’t want to try it out and see how it works.” Union members’ views were divergent on when and how theater would return, and what it will be when it does—some, said Penn, “can imagine wearing masks and some can’t. There are a lot of different opinions right now.” As they wait, members are working on planning projects, and mulling if films may get greenlit before theater. Choreographers are teaching online.

“I was scheduled to have a concert I had written and conceived perform at the end of March, and it would have been a wonderful thing for me,” said Masse. “But all is not lost, we will do that concert one day I hope. I think this has just been much harder on those of us without savings, whether that’s due to student debt or the bad luck of being on several flop shows in a row, or working on projects for the future. It isn’t anyone’s fault and it is how the business is, but it has definitely made this experience harder to endure.”

Marin is hoping to start working some time in August to prepare for shows in September, and then actually do shows in September. “I'm optimistic that there will be shows and events to attend as soon as it's safe—but what will that mean?”

Marin feels fortunate to be a member of the union, IATSE Local One. The union has connected members to many training resources and opportunities to receive certification during the shutdown, as well as keeping up a constant stream of information. “I feel like I can trust that if they clear their membership to begin working again, it will either be safe or appropriate safety measures will be enacted,” said Marin.

“Outside of the health insurance, musicians need the business as a whole to recognize that if we are discussing a musical, the orchestra is imperative and is not optional or superfluous,” said Paul Masse. “We can’t have that rhetoric anymore, and we all need to be better about calling it out.”

John Curvan anticipates that Broadway “will be one of the last things to come back” and may look to do some other work as he waits for it to restart. “Broadway is a huge thing for New York City and a huge thing for tourists. Entertainment and tourism are hand-in-glove. If one comes back and the other doesn’t, it is not going to work. But Broadway will come back. Theaters lived through the Plague. Look at Shakespeare’s time. Theaters can close for years, but they always come back.”

“I’m not a health expert nor am I an expert in marketing or budgeting, said Masse. “But if I didn’t feel strongly that theater and the arts more broadly are essential, I wouldn’t have spent the last 20 years making a precarious living doing it. I worry that we've allowed certain things to happen tacitly that we may not be able to get back. We have let the words ‘social’ and ‘essential’ be redefined in pandemic-speak. And we have discounted the value of living versus merely surviving.

“If all of the joy in life has been eliminated: restaurants, sports, theater, travel, love, sex, nature... what have we done this for anyway? We need to shift back our meaning of ‘essential.’

“Everything we do in life carries inherent risk; that does not mean we should be irresponsible and throw all caution to the wind, but we also need to wisely peel the Band-Aid off without debasing ourselves as humans and eschewing our basic human need of touch and community and love and laughter and shared experience. The theater cannot be replaced by Zoom readings. It just can't.”

Nathan Gehan feels that optimism will bloom after New York City begins to reopen (due to start officially tomorrow, Monday); he is also confident in the Broadway League and unions to formulate effective protocols for reopening. “I know the intention of Broadway is to come back and not have socially distanced shows,” said Gehan. “I think an audience only comes back, and performers perform, when there are no longer spikes in the virus and all the measures have been well-publicized to protect everyone.”

If the early fall saw a dramatic decline in deaths, and viral transmission, Gehan could imagine producers rushing “fast and furious” to put up a show—especially if it was a solo show of some kind, like Laura Linney’s My Name is Lucy Barton.

Producers like Daryl Roth also remain focused, and optimistic. “Theater is always a big risk, it’s one of the riskiest businesses you can imagine. I kind of feel I want to be a cheerleader to do what I can, so that once ‘the gates are open’ so to speak, once the safety measures are in place, I will do all I can to support theater. Theater is just risky. It is not a business for someone who is risk-averse.”

Roth said she would “think long and hard” about the kinds of post-pandemic works she would support, and the kind of theater people would pay to see.

“I think people want to have joy, and have moments of joy, and be engaged and also lift their spirts. There are many ways to lift spirits. You have to do shows that have meaning and can fill the soul, which is what theater should be, but now more than ever it is important to give that to people. We have to refill souls in a way because they, we, been drained. God knows, after 8, 9, 10 months they will need such replenishment. We’ve got to do something. We’ve got to keep going.”

“Financial and moral support is greatly appreciated,” said Victoria Velazquez of Women of Color on Broadway. “If you can, please donate to our organization, and check our website to learn more about volunteering and what we do and what you can do. I think Broadway will be back, I don’t think it’s going anywhere. There is something special about experiencing a live performance, and it cannot be replaced by any virtual alternative.”

When thinking about the future, Paul Masse recalled watching Slave Play in January and the literal and metaphorical stage-sized mirror the audience was faced with.

“That kind of impact is just not possible without being in a room full of strangers in uncomfortably-distanced seats at the Golden Theatre on West 45th Street where before the play even begins, there is a clear racial divide to the theater based on the price of tickets—and we sit amongst it.

“I personally don’t feel we can wait for everything to be perfect and safe; our ability to hold up a mirror to society through theater is so desperately needed right now. Our progress as human beings with empathy cannot rest on a vaccine or cure—it may never come. We don’t have time to wait when it comes to racial justice, as just one example. There are other pressing matters and we have to just accept that there is a risk to living life.”

It was vital, said Masse, to “stand with our black and brown colleagues against the atrocious racism we’ve been tacitly allowing for way too long. I am personally reflecting on how best to do that myself. It is no longer enough to be a supporter or ally, we must submit our privilege to them and use it for action.”

“I would like to encourage everyone to be safe in these crazy times," said Victoria Velazquez. “I’m proud of all the people who are speaking out on the injustices in our society. If you’re going to protest, please remember to wear your PPE, and wash your hands as much as possible. We are still living in a pandemic, so please take the precautions seriously!”

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.