Can he do that? Tony Evers followed a Wisconsin tradition when he increased school aid for 402 years.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

MADISON - Gov. Tony Evers raised eyebrows Wednesday when he deployed a broad power unique to Wisconsin governors that allows them to use vetoes to increase state spending above levels set by lawmakers — in this case, extending funding increases for schools for centuries beyond the lifetimes of everyone involved in crafting the next state budget and their great-grandchildren.

It's the second time Evers, a former state superintendent and public school educator, has used his partial veto authority to increase funding for public schools. The first time, in the 2019-21 state budget, prompted Republican lawmakers to amend the state constitution to put limits on his veto pen but Evers is still able to make broad and unexpected changes to the spending plans lawmakers give him.

But the governor's partial veto power, while still broad, has been scaled back considerably over the last few decades.

Gone are the Vanna White and Frankenstein vetoes

At one time, governors could veto individual words to create new words — known as the Vanna White veto — or strike words from two or more sentences to make new sentences, known as the Frankenstein veto. Voters eliminated governors' ability to make such changes in 1990 and 2008, respectively.

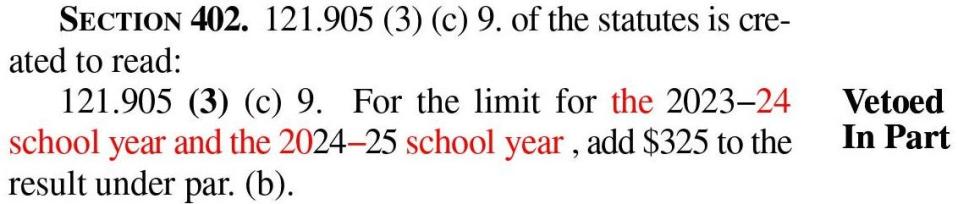

Evers crafted the four-century school aid extension by striking a hyphen and a "20" from a reference to the 2024-25 school year.

Rick Champagne, director and general counsel of the nonpartisan Legislative Reference Bureau, said Evers' 400-year veto is lawful in terms of its form because the governor vetoed words and digits.

"Both are allowable under the constitution and court decisions on partial veto. The hyphen seems to be new, but the courts have allowed partial veto of punctuation," Champagne said.

"We have not yet undertaken an analysis of how the allowable per pupil increase applies to a period of time as opposed to a specific school year. Governor Evers’ veto message clarifies the intent of the veto," he said.

In his veto message, Evers wrote: "I object to the failure of the Legislature to address the long-term financial needs of school districts. This veto makes no changes to the per pupil revenue limit adjustment provided in the 2023-24 and 2024-25 school years and provides school districts with predictable long-term spending authority increases."

Republican lawmakers who control the state Legislature will likely try to either override the veto or propose to change it in the next state budget. A future governor could also take action to eliminate the 402-year-long funding increase.

Scott Walker had the 'thousand-year veto'

Until Evers' budget action on Wednesday, governors had used vetoes to increase state spending above levels set by lawmakers 31 times since 1991 and increased bonding levels seven times during that time, according to a 2020 analysis by the nonpartisan Legislative Reference Bureau.

Former Republican Gov. Scott Walker also used his office's veto authority to extend one measure in the 2017-19 state budget to last indefinitely, known as the "thousand-year veto." That year, Walker used partial vetoes to turn the deadline to end a program allowing school districts to raise revenue limits for energy efficient projects from 2018 to 3018. In another veto in the same budget, Walker delayed the start date of another program to 2078 from 2018.

The vetoes were challenged in court but the state Supreme Court sided with Walker, saying the lawsuit was filed too late.

Evers' vetoes show the power of Wisconsin governors

In all, Evers' 51 vetoes were a reminder that Wisconsin gives its governors some of the most sweeping executive powers in the country and allows them to hold the upper hand in budget standoffs.

In 1973, Democratic Gov. Patrick Lucey removed a digit, making it so the state could borrow up to $5 million for highway projects, instead of $25 million. In the 1975-77 budget, Lucey removed the word “not” from a provision related to tourism promotion, making a 50% minimum on cooperative advertising a 50% maximum.

Democratic Gov. Martin Schreiber followed Lucey’s lead in 1977 to alter a provision that would have allowed taxpayers to opt to contribute $1 to the state’s public campaign finance fund. With Schreiber’s partial veto usage, taxpayers were instead authorized to choose to have the state contribute $1 to public financing from its general fund.

In a move the Legislature overrode, Democratic Gov. Tony Earl in 1983 reduced a five-sentence paragraph to one 22-word sentence, sending appeals of municipal waste disposal determinations to courts instead of the state Public Service Commission.

In the 1991-93 state budget, Republican Gov. Tommy Thompson struck words, digits and punctuation marks from a provision related to the state’s school property tax credit to instead create a general school tax credit, adding a $319 million appropriation to the bill.

In the same budget, Thompson took away the Joint Finance Committee’s ability to modify or reject his spending plan for aid to Milwaukee Public Schools, making approval the committee’s only option.

Gov. Jim Doyle turned $140 million into $1 billion

In the 2003-05 budget, Democratic Gov. Jim Doyle used his partial veto authority to increase the state’s borrowing authority for highway projects from $140 million to $1 billion.

In the following budget, Doyle transferred $427 million from the state’s transportation fund to its general fund, directing most of that money to public schools.

Wisconsin governors have long wielded some of the most expansive veto powers in the country, but the state Supreme Court limited their authority in 2020.

The decision was fractured, with different justices saying different limits applied to governors. A majority failed to set clear rules for what could be done with future vetoes.

Wisconsin governors have long been able to strike out words in budgets to create sentences that differ sharply from the ones legislators wrote. The state Supreme Court for decades upheld those powers.

It ruled in 1988 that then-Gov. Thompson could create new meanings by eliminating individual letters from words. (That practice — which came to be known as the "Vanna White veto" in honor of the TV host who turns letters on "Wheel of Fortune" — ended two years later, when voters amended the state constitution.)

The 1988 court decision was in line with others before and after it that concluded the veto powers of governors are vast.

Wisconsin's Supreme Court hasn't agreed on specific rules

That changed in 2020 in response to a lawsuit brought by three taxpayers represented by the conservative Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty. They argued Evers had overstepped his bounds with budget vetoes he issued in 2019.

That ruling was a blow to Evers and future governors, but its exact effect isn't clear because the justices couldn't rally behind specific rules about what types of vetoes are allowed.

Justices Rebecca Bradley and Daniel Kelly concluded vetoes could be used only to block a specific measure passed by the Legislature. Justices Brian Hagedorn and Annette Ziegler argued for a different standard, writing that governors could use vetoes to slightly modify budget provisions but could not use them to enact new policies.

Then-Chief Justice Patience Roggensack contended partial vetoes were acceptable as long as they dealt with the same subject matter as what was in the original budget provision being vetoed.

The court's liberals, Ann Walsh Bradley and Rebecca Dallet, sided with Evers on all his vetoes.

How a future case over vetoes might play out is hard to determine because of the last decision and because of changes on the court since then.

All the justices are willing to accept partial vetoes that eliminate entire sections of the budget. What they differ on is other types of vetoes, where parts of sections are removed.

Why Republicans began using 'cannot' instead of 'may not'

For their part, Republican lawmakers sought ways to limit Evers' options. They largely avoided creating new programs in the budget to avoid the possibility that Evers would rewrite their words into something they never imagined.

In one of their final budget amendments, lawmakers replaced the phrase "may not" with "cannot" in dozens of places.

"May not" has been a potent term in past budgets because governors were able to strike out the word "not" and leave in place the rest of a sentence — resulting in the opposite of what the Legislature intended.

Molly Beck and Jessie Opoien can be reached at molly.beck@jrn.com and jessie.opoien@jrn.com.

THANK YOU: Subscribers' support makes this work possible. Help us share the knowledge by buying a gift subscription.

DOWNLOAD THE APP: Get the latest news, sports and more

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: How Wisconsin governor used veto to extend school aid for 4 centuries