I Took the Advice in ‘Men Are From Mars Women Are From Venus’ 30 Years Later

There is no door separating the bedroom from the living room in my 650-square-foot apartment, where my husband, Mark, and I have spent the past year together. It’s not like we were having problems qua problems when I picked up a hardcover copy of the 1992 self-help best seller Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus: A Practical Guide for Improving Communication and Getting What You Want in Your Relationships, by John Gray, Ph.D., but after a year of quarantine, we weren’t exactly in any position to be turning down marital advice in any form. Not to mention, Mark had recently started saying “Cool, cool, cool” every time one of his coworkers asked him to do anything, a habit I loathe. I don’t want to kill him, but I don’t not want to kill him. I’m sure he feels the same way about me.

I viewed it as an ironic little joint reading project, and Mark was game. Besides, it was Covid—what else were we doing? We could even commit to the bit and order a fondue set and some royal-blue wineglasses to drink pinot noir out of like it was really the nineties. In other words, we could pretend we were our parents, who seemed to have had it all so together at our age.

Some version of them, anyway. If I was being honest with myself, the project was more than ironic. My suspicion was that advice for a happy marriage hadn’t changed much in thirty years. This might have been a comforting thought for some, but for me, it was a little menacing: My parents ended up divorcing, and not amicably. My hope was that I’d read the terrible advice they’d gotten and be able to confirm something: Of course they split! With advice like this? They were doomed!

And what about us? We’re cool, we’re skeptical. We’re not the types to get wrapped up in self-help books. But could spending the spring of my thirty-second year with the marriage advice on (aggressive) offer to my parents when they were thirty-two teach me and my husband anything—even by counterexample? Could it teach any of us anything? Couldn’t hurt to try.

It begins like this:

Imagine that men are from Mars and women are from Venus. One day long ago the Martians, looking through their telescopes, discovered the Venusians. Just glimpsing the Venusians awakened feelings they had never known. They fell in love and quickly invented space travel and flew to Venus.

The book was a huge hit right around the time of Princess Diana’s separation—when game night was Trivial Pursuit and sushi restaurants started showing up in strip malls—and no wonder, with an opener like that. The book is not a scientific one but a work of pop psychology. Nonetheless, it spent 235 weeks on the New York Times best-seller list and sold seven million copies in the U. S. between 1992 and 1999. Bridget Jones read it. In 2000, it became a talk show. Gray followed up with a series of seminars both public and private and speaking engagements across the globe.

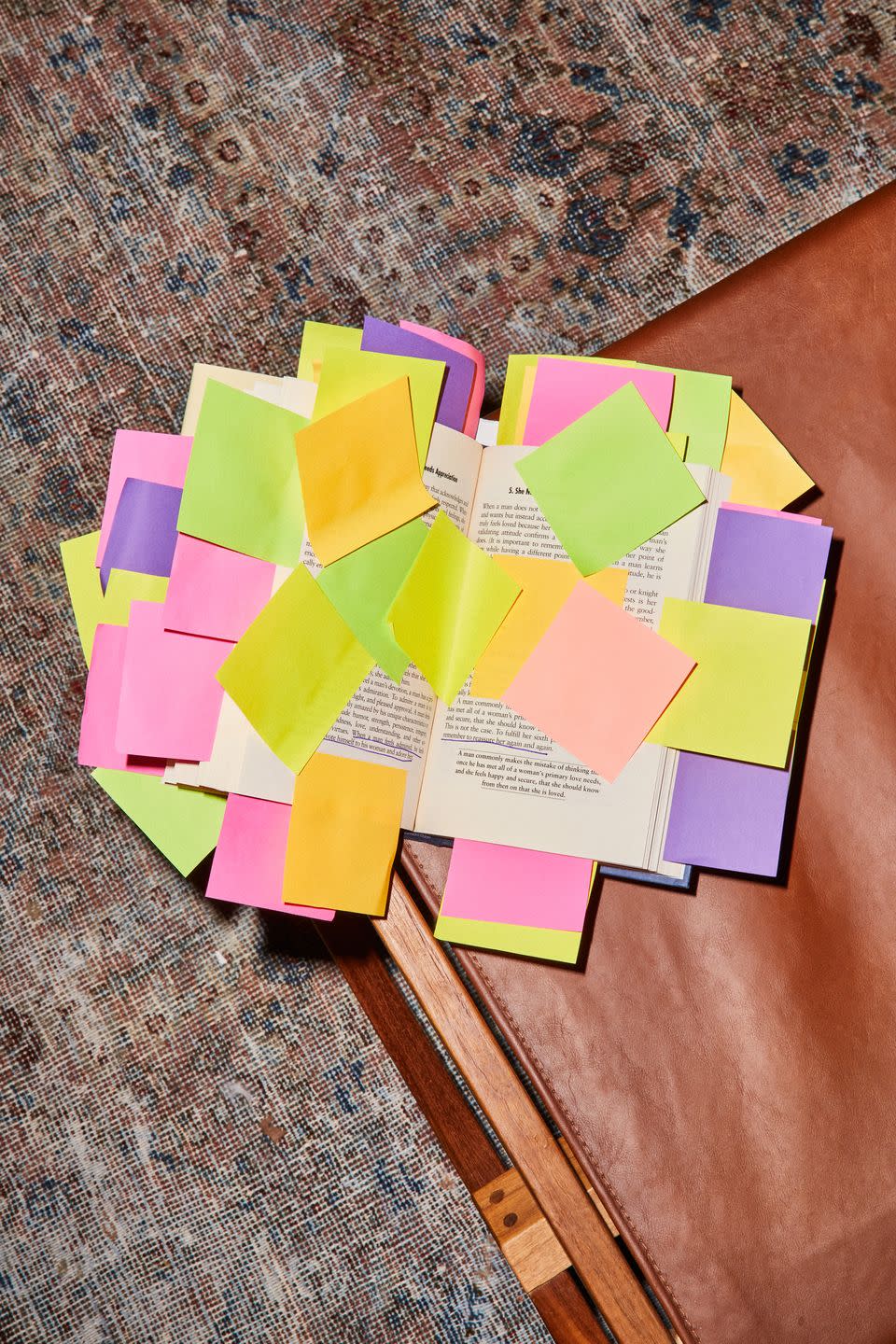

In the course of our joint study, Mark and I learned that while “Martians tend to pull away and silently think about what’s bothering them, Venusians feel an instinctive need to talk about what’s bothering them.” As if the book’s central planetary metaphor weren’t enough, Gray invokes, among others, a dragon, a cave, a wave, and a rubber band to describe how people tend to operate in heterosexual relationships. Women get advice on how to tell a story so it won’t irritate her man. (Tell him the ending first.) At one juncture, we’re introduced to a points system and given 101 ways to score them. (They range in their specificity from “Validate her feelings when she is upset” to “Offer to build a fire in wintertime.”) We are told that the correct number of hugs per day is four. In addition to having a dazzling command of metaphor, Gray uses repetition as a key rhetorical tool. He bolds main ideas and makes liberal use of lists and tables. I thrilled to imagine the joy that would come when he discovered PowerPoint.

Martians, who enjoy the big game and being left alone after work, are simple creatures, and so are Venusians, who “listen to self-improvement tapes” for their kicks and share wine with friends. Gray assures us that neither is superior. The entire premise is easier to absorb if you’re a reader who puts stock in the phrase “the opposite sex,” which we encountered so many times in the text that I started to wonder if Gray had popularized the phrase. Many shared eye rolls aside, Mark reported pleasant feelings of recognition. After all, in spite of well-meaning feminist parents, he’d been raised to act exactly as Gray anticipated, and so had I. Mark mostly agreed with Gray’s assertion that a “man’s deepest fear is that he is not good enough or that he is incompetent.” In the margin next to that same sentence in my copy, I’d written “lol.”

Things got worse. Mark surprised himself by appreciating Gray’s openness about men’s sensitivities and recognized the cultural messages that teach men to avoid sharing what’s inside. At times, Gray verged on the profound. (“Not to be needed is a slow death for a man.”) Mark admitted that he agreed with Gray about men’s outsize need to be trusted. He chafed when I asked if he’d washed his hands after coming back from the store. “Can’t you trust me with basic hygiene?” he reasonably wanted to know. (I could not. It’s a pandemic!) He had an easier time taking the good and tossing the bad than I did: “It’s a time capsule from the nineties,” he said, shrugging. “Not all messages have to speak to all people at all times.” I, on the other hand, found myself feeling afflicted every time I encountered any good advice (when someone says they’re “fine,” believe them until they say otherwise? impossible), and it wasn’t just because I felt caricatured. (I do not, in fact, enjoy shopping!) It was also that the snob in me didn’t want these dicta to apply to my life. I’m not a simple creature. I am a skeptic. I subscribe to The New York Review of Books, for God’s sake! If I were to seek advice on my marriage at all, it would be from someone with better taste in fonts.

That would be Esther Perel, the Belgian psychotherapist and author of the 2006 book Mating in Captivity. No relationship guru has achieved penetration in millennial bedrooms quite like she has. Twenty million people have watched her TED talks. Her books have been translated into more than twenty-five languages. Her audience is neither implicitly nor explicitly heterosexual, nor is it even necessarily monogamous. Many in her audience view gender as inherently fluid. Her world is earthbound, and I suspect that’s where its popularity comes from. Mark and I both listened to her podcast Where Should We Begin? when it premiered a few years ago. The premise of the show is that couples come to her with a seemingly intractable problem and she records them working it out in real time. The issues the couples face are complicated—immigration, abandonment, their relationships with their fathers—all of which give it a mouthfeel of intellectual heft.

Perel is the thinking person’s pop psychologist. The implicit project is understanding the human condition of attraction and doesn’t require admitting there’s any kind of problem with yours. Perhaps cannily, there’s no whiff of self-help in her materials. Perel places emphasis on separateness in a way that strikes me as realistic, observing that we often ask way too much of our partners: We want them to be our best friends, our sexual partners, our caretakers, etc. And not only is that a lot to ask of a single person, but sometimes those modes can make for uncomfortable mixes. In May 2020, two months or so into the pandemic, The New Yorker’s Rachel Syme interviewed Perel, seeking advice about navigating lockdown with a partner. She hit that refrain about couples needing to “regulate togetherness and separateness all the time, with confinement or without.” She even remarked, as though somehow aware of our apartment’s door problem, that “you don’t need to have a door to leave the house. You can be somewhere there without being absolutely present.” Mark and I both nodded along to Perel with none of the embarrassment of recognition I experienced with Men Are from Mars.

Is it fair to pit Perel and Gray against each other? Well, they do have one undeniable similarity: Whether you agree with either of them or find them full of it, seemingly everyone over fifty-five has heard of Men Are from Mars and seemingly everyone under fifty-five has heard of Perel. Both have merchandised with gusto. When you finish their books, both have online workshops, seminars you can sign up for, and talks to attend. Gray now even has a series on YouTube, where his daughter, Lauren, repackages his principles for a younger audience.

This article appears in the April/May 2021 issue of Esquire.

subscribe

I found Lauren captivating. There was something familiar about her face, though I couldn’t place it. In her videos, she has the bearing not of a psychologist but of a commercial actor, detailing the ways in which her dad’s approach to “the opposite sex” had improved her relationship with her partner, Glade. If she harbored any skepticism about that phrase at a time when many in our cohort had arrived at the conclusion that genders weren’t opposites so much as locations along a spectrum, she didn’t betray it.

Lauren makes an appearance as a baby in the introduction to my 1992 copy of Men Are from Mars. Only on my second reading, though, did I notice what suddenly felt obvious to me: Both John and Lauren Gray are from my hometown of Mill Valley, California. It took me approximately three clicks on Facebook to learn that Glade, of YouTube fame, and I had even been in the eighth-grade musical together. (He was excellent.) To my disappointment, in spite of what struck me as an almost cosmic coincidence, Lauren declined an interview. Luckily, her dad agreed to chat.

I reached Gray by Zoom at his home in Mill Valley, where his books were arranged behind him, covers out for my benefit. It became clear immediately that, almost thirty years on, Gray is sticking to his message. He remains focused on gender differences, with a new emphasis on hormones that doesn’t show up much in the original text. (For that, you’ll have to check out 2017’s Beyond Mars and Venus, which Gray held up to the camera for me several times.)

Gray told me that he worries about how some psychotherapy “reinforces victimness” when it should be focused on looking inward and asking what one did to cause the unhappiness in their life. He’s aware that this has the potential to cause offense and claims to have received death threats in the nineties for his work, a problem that has only gotten worse thanks to what he sees as “cancel culture” run rampant. He called the notion that gender is a mutable concept “nonsense.” But when I asked him about how his books might apply to trans, nonbinary, or gay readers, he displayed no animus toward those readers at all, beyond pointing out that his books are really written for cisgender (my word, not his) heterosexual couples. Any benefit to relationships between people other than cisgender men and women from his books or seminars would be wonderful but incidental. The conversation had the uncomfortable feeling of talking to a friend’s dad who had just misgendered someone without meaning to.

He went on to tell me that “self-medicating” by masturbating lowers your testosterone. He recommends that readers of Esquire limit themselves to no more than one session of sex with a partner per week—and don’t masturbate in between. He views ejaculation as a problem area: “I have learned how to have orgasmic sex without ejaculation,” he bragged, elaborating that “it takes muscle training, it takes abs.” The uncomfortable feeling of listening to a friend’s dad deepened.

But viewed generously, his main ideas are hard to quibble with: He quite sensibly suggested that making ourselves happy is “an inside job,” one we can’t outsource to our partner, and that we can view our differences in a positive light if we have the right attitude.

He also spoke with generosity and real admiration for his wife, Bonnie, who contributed meaningfully to his work in the thirty-three years they were married, once memorably underlining Gray’s classic point about allowing your wife to drone on about her day without complaint by saying, “I know you think this is a waste of time, but it’s really helping me.” (I’ve since tried that line out on Mark, who, I swear to you, softened as soon as I said it.) When I asked if Bonnie was a psychologist as well, Gray said, “Oh,” as if remembering himself, “Bonnie passed two years ago.”

Childhood’s greatest pleasure might be the illusion that our parents have some idea what they’re doing. The slings and arrows of growing up teach us, of course, that no one does. Parents fight, they get divorced, they make bad real estate decisions, they take jobs they don’t like, they buy Volvo station wagons with black interiors. In other words, they are human. Between shopping for windbreakers and watching episodes of Seinfeld,they were embarking upon the project of understanding each other, and they found they needed some help with that.

It turned out that reading Men Are from Mars three decades on did hurt. At first I found it heartbreaking to think of a generation of parents looking for answers in a book with a conceit as ludicrous as this one’s. But as my experiment with Mark drew to a close, it struck me as perhaps even more heartbreaking to imagine my parents not looking for answers. Geography felt, suddenly, less than coincidental: With great pain I realized that not only had my parents never read his book, but for years, they’d lived down the street from this supposed guru and still they could not make it work. Couldn’t they have indulged in a little magical thinking if it could have helped? Couldn’t they have been a little less cool, a little less skeptical? A little less, in other words, like me?

And as much as it hurt, did it help? I can say this: Though I’d ridiculed Men Are from Mars, I was desperate for it to teach me the lessons that my parents missed. Desperate to humble myself before something I found so silly, knowing full well that to reserve my skepticism meant quite possibly feeling stupid as hell. Maybe we make our parents’ mistakes again and again, and the gurus squeeze millions out of us, generation after generation. But whether it’s 1991 or 2021, each night we close the bedroom door (should we be so fortunate as to have one), discreetly stow small books that promise to rid us of our failures into the drawers of our bedside tables, lean over to our spouses as we turn off the light, and believe, whether it’s science fiction or not, that in the morning we’ll be just a bit better to the person we love most.

You Might Also Like