Top SBA official oversaw PPP, then did work for one of its worst offenders

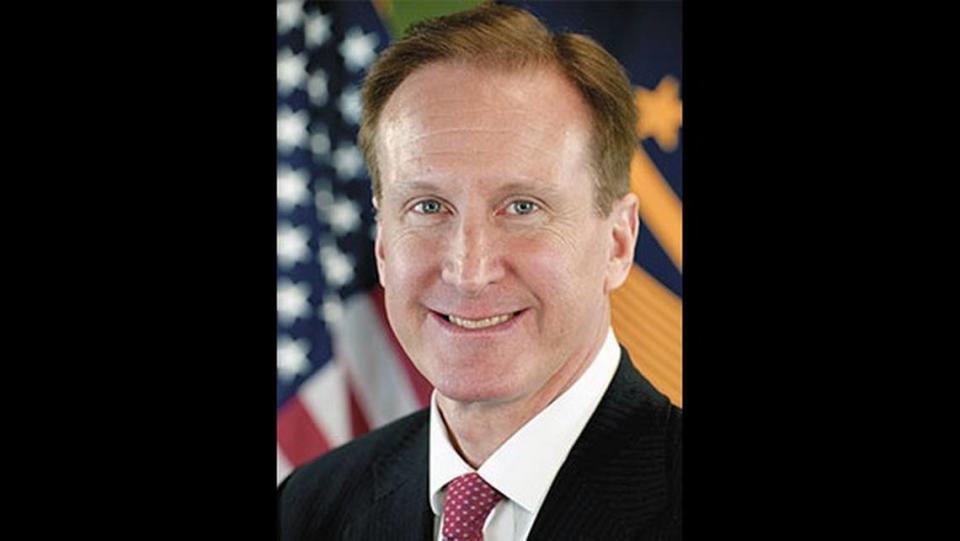

As the chief of staff at the U.S. Small Business Administration, William Manger oversaw the agency’s implementation of the $800 billion Paycheck Protection Program.

The signature small business federal relief program introduced early in the COVID-19 pandemic offered loans up to $10 million that were forgivable if used for approved expenses such as payroll.

The money for the program came from the federal government, but the SBA relied on lenders, including thousands that had never previously worked with the agency, to vet applicants and help get money as quickly as possible into the bank accounts of struggling small businesses. Lenders were paid a commission for their work, on a sliding scale based on the size of the loan.

After his exit from the agency in January 2021, Manger went on to do work for a company identified by congressional investigators as one of the worst offenders, a technology firm called Womply.

Womply was not itself a lender, but created an online portal for prospective PPP applicants to submit their information and then funneled applicants to various banks and lenders the company partnered with.

The company’s partners, including Coral Gables lender Benworth Capital and Orlando-area lender Fountainhead, would eventually come to have little faith in the services the company provided, as they became convinced that Womply had facilitated extensive fraud. Some of the allegedly fraudulent PPP loans facilitated by Womply were obtained by a suspected Florida drug gang.

Womply, which had previously provided reputation management, marketing and data analysis services for small businesses, told lenders that it would vet PPP applicants and pass on only those applicants that met requirements for the program, which was targeted at existing businesses and excluded candidates with records of financial crime or who were facing felony criminal charges.

Under the terms of the agreements it signed with its partners, Womply typically kept the lion’s share of the fees generated by these loans.

The company would ultimately push through more than 1.3 million loans that were approved, adding up to $16 billion overall. The fees generated by those loans helped the company achieve nearly $2 billion in revenue in 2021. And the company also obtained two PPP loans in 2020 and 2021 under its corporate name Oto Analytics, Inc. which totaled $5.1 million.

But Womply’s partner lenders said that the company’s technology seemed to be “put together with duct tape and gum” and accused it of facilitating “rampant fraud.” The company was banned by the SBA from doing business with the agency after a scathing report released last December by the U.S. House Oversight Committee’s Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis, which contained the accusations from Womply’s partners.

The company became a favorite conduit for PPP loans for a drug gang in the Orlando area called the Army Gang whose alleged members were arrested as part of the Metropolitan Bureau of Investigation’s Operation X-Force in 2021, according to the congressional report.

“Man, that’s the website that, that really hittin’ bih,” an alleged gang member said of Womply in a conversation picked up on wiretap, using slang for the word “bitch.” “That’s the PPP loan bih.”

The revolving door

When Manger, a Trump administration appointee, left the SBA on January 20, 2021, he was both the agency’s chief of staff and also oversaw its office of capital access, which worked with banks to make loans available to small businesses.

It isn’t clear when he began doing work for Womply, but after he was elected in 2022 as a trustee of Southampton Village, a ritzy town in the Hamptons, he listed himself as a consultant for Oto Analytics, Inc. on his financial disclosure form.

But a lawyer representing Womply said Manger’s characterization of his work for the company was not correct.

“Mr. Manger is not, and has never been, a consultant for Womply,” said Alexander L. Cheney, an attorney at Willkie Farr & Gallagher. Rather, he said Manger was paid to be a “testifying expert” in arbitration between Womply and one of its partner lenders, Benworth Capital, over fees Womply says it is owed by Benworth.

“The SBA is aware of both the arbitration and Mr. Manger’s role as expert,” Cheney said.

Reached by phone, Manger wouldn’t comment further on the exact nature of his role.

“I don’t really have anything to add,” he said.

Responding to written questions, the SBA didn’t say whether it was aware of Manger’s work for Womply and whether it signed off on it.

Employees of the SBA who “occupied a position involving discretion over, or who exercised discretion with respect to, the granting or administration of SBA Assistance” are barred from working as an “employee, partner, agent, attorney or other representative” of any company that received SBA assistance for two years after the assistance is granted or administered.

Federal revolving-door regulations are typically focused on restricting the ability of senior officials to lobby their former employers after leaving, but the fact that the SBA has specific rules connected to SBA assistance is because of the unique nature of the agency, which is heavily involved in helping small businesses obtain loans and other funding, said Kathleen Clark, a law professor at Washington University in St. Louis who specializes in government ethics.

“It speaks to the concern that SBA officials will grant assistance with an eye toward future employment,” she said. “The regulation is a way toward preventing that from happening.”

The SBA confirmed in a statement that PPP loans, such as those obtained by Oto Analytics, count as SBA assistance. It declined to say which employees would be subject to the restrictions.

Manger did, by his own telling, oversee the PPP program and sent letters to several local Planned Parenthood offices asking them to return PPP loans they had been awarded or prove that they were eligible for the loans. The agency had, after outcry from Republican lawmakers, determined that the local Planned Parenthood offices were too closely affiliated with the national organization and ran afoul of the eligibility rules for the loans, which were available only to businesses with fewer than 500 employees.

It isn’t clear, however, whether Manger would face any consequences if he was in violation of the law. The only penalty listed is for current SBA employees, who face the possibility of discipline, “including removal or suspension,” for violating the standards of conduct and restrictions and responsibilities for current and former SBA employees.

There’s no indication of how much Manger was paid for the work he did on behalf of Womply. His Southampton political disclosure indicates only that the work paid him more than $5,000 for the calendar year covered by the report.

Manger listed his hourly rate as $650 for preparing an expert report in another case on behalf of small business owners who brought a lawsuit against the PPP lender Capital Plus Financial. The small business owners who brought the suit said Capital Plus Financial had approved them for PPP loans but never actually delivered the funds.

In his expert report, Manager indicated that he “oversaw and led the SBA’s implementation of the Paycheck Protection Program,” which included, “promulgating PPP-specific rules and guidance, implementing PPP-specific processes at the SBA, and communicating with lenders, trade associations, government agencies and members of Congress.” He indicated he has been an independent consultant since leaving the agency.

Womply touted its close relationship with the SBA as reason for lenders to partner with it. The company’s chief executive officer, Toby Scammell, appeared in an online seminar in early 2021 with Manger’s deputy at the office of capital access, Bill Briggs, and lenders who worked with Womply cited their impression of Womply’s close connection with the SBA as a big factor in their decision to partner with the technology company, according to the congressional report.

The report raises the question of whether Womply should have been allowed to participate in the program at all, since Scammell had pleaded guilty to charges related to insider trading in 2014 and was barred from participating in the securities industry. The SBA has the right to prohibit entities from doing business with the agency that have fraud convictions in the previous seven years or a record of other unethical behavior. Scammell oversaw Womply’s anti-fraud efforts and, according to the congressional report, stymied efforts by SBA’s Office of the Inspector General to investigate potentially fraudulent loans the company had passed on to its lenders.

The SBA barred the company from doing work with the agency on Dec. 7, 2022 in response to the findings in the congressional report and said that it would investigate “appropriate action against their management, owners, and successor companies.” The agency declined to say whether Womply is still suspended from doing work with the agency or the status of the investigation.