Torches and birchbark canoe guide Ojibwe man as he revives ancient tribal spearfishing tradition in northern Wisconsin

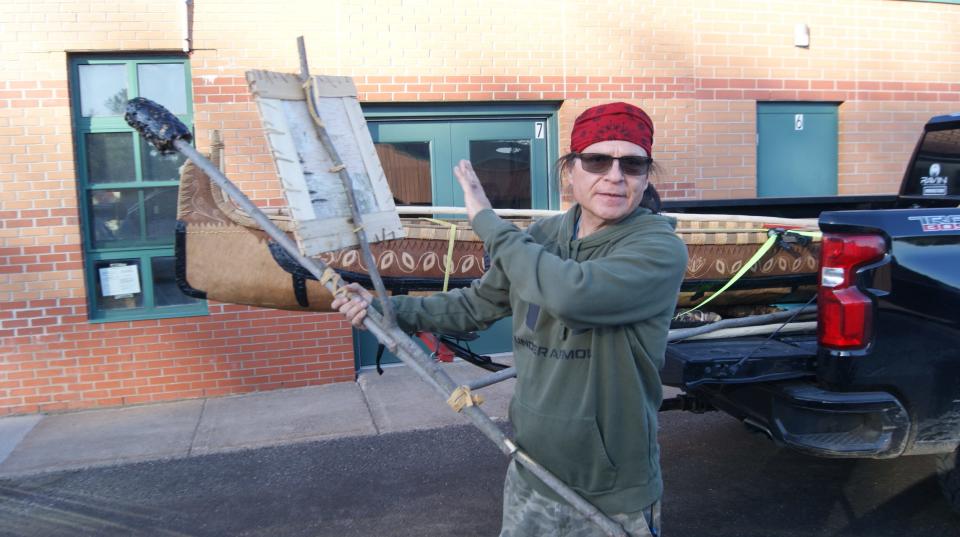

LAC DU FLAMBEAU - People along the shore were yelling “Good luck, Wayne!” as Wayne Valliere paddled into the starlit night aboard his torch-laden birchbark canoe equipped with a handmade spear.

One of his aims was to show how these ancient techniques can be just as effective, if not better, than modern practices for harvesting fish.

“It hasn’t been done this way in 200 years,” Valliere, 56, said. “This birchbark canoe is made the way it was 500 years ago. Everything was put together using natural materials.”

The Lac du Flambeau (lake of torches) Ojibwe Reservation, where Valliere lives and works as a tribal citizen, derives its name from 17th-century French explorers who marveled at the way the Ojibwe people filled the lakes with torches at night in the springtime on their canoes while spearfishing walleye.

The fishing is done at night in the spring because that’s when the walleye move to the shallows to spawn, making it easier to catch them.

These days, tribal citizens practice their right to spearfish using modern fishing boats, small spotlights and metal spears.

But Valliere, whose Ojibwe name is Mino-Giizhig, is trying to revive traditional ways before they are lost forever.

And it doesn’t stop at spearfishing.

At the Lac du Flambeau Ojibwe Elementary School on the reservation, Valliere teaches students an array of traditional activities, including maple sugar production, deer hide tanning and even tobacco cultivation.

The tobacco, or asemaa, is used in traditional ceremonies in which it is sprinkled on the ground to give thanks to the Creator before harvesting anything in nature.

“It’s not about teaching culture, but teaching culturally,” Valliere said.

Rather than explaining those practices from a book to memorize answers for a test, his is a hands-on, experiential approach by showing students how it’s done and having them do it.

“We teach three-dimensionally, using all the senses,” he said.

RELATED: 'These canoes carry our culture': Ojibwe artist recognized for lifetime achievement

Traditional teaching

Valliere has been learning the traditional crafts of his ancestors since he was 14, after tribal elders in the 1970s encouraged him to learn what he could before it was lost to the people.

“It’s been a journey for me since I was a young child,” Valliere said. “There’s been great cultural loss. … My family was a traditional family who hunted and gathered. That’s how we ate.”

He started his artistic journey by painting scenes of traditional and historic Anishinaabe life and soon developed a passion to recreate some of the craftwork he was depicting on his canvas.

Valliere learned from elders, such as the late Joe Chosa and Ojaanimigiizhig, and started to create beadwork, pipes, weaponry and other crafts.

He even reverse-engineered artifacts he discovered at museums.

But Valliere is probably best known for building traditional birchbark canoes.

Constructing more than 30 birchbark canoes so far, he is considered a master builder and said it can take about two months of total work to make just one.

Get news in the palm of your hand: Download our app

The process of canoe building starts with the arduous work of searching for just the right birch tree of mature age and a certain length that can handle the right amount of stress.

Then Valliere needs cedar roots for sewing the craft, and the roots can only be harvested at a different time of year than the birch.

He is one of a handful of traditional canoe builders in the world, and he believes the canoes are more than merely water craft.

“These canoes carry our culture,” he said.

In 2020, Valliere was one of nine traditional artists from around the country selected for a National Heritage Fellowship by the National Endowment for the Arts for his birchbark canoe work.

Spearfishing an important tradition

Valliere and his canoes are often the subject of documentaries. Filmmaker Michael Raymond is working with him to produce a series of educational videos for a new nonprofit they started together called Niigaan.

Raymond went out to film Valliere this early May on Pokegama Lake on the reservation near the Lake of the Torches Casino.

About two dozen students also went along for the experience with some helping to document Valliere’s activities on his birchbark canoe and others trying spearfishing the modern way.

Spearfishing remains an important tradition for the Ojibwe people, as Valliere and others had fought for the right to spearfish in the 1980s and 1990s.

The rights for the Ojibwe to hunt and fish off-reservation in what is known as the Ceded Territory, which includes much of the Wisconsin Northwoods, are guaranteed by U.S. and tribal law through early to mid-19th century treaties in exchange for the government taking Ojibwe land.

Wisconsin state government had ignored or eventually forgotten about these treaty rights after statehood, but Anishinaabe people would still sometimes exercise their rights clandestinely to feed their families and risk citation or arrest from state game wardens.

Then, in 1974, brothers Fred and Mike Tribble, who are Lac Courtes Oreilles tribal citizens in Wisconsin, alerted the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources that they intended to fish off-reservation and were charged.

The brothers challenged the citations in federal court and won against the state in a 1983 ruling known as the Voigt Decision. Judges in following years repeatedly upheld the Anishinaabe people’s right to fish and hunt off-reservation in subsequent rulings and struck down state appeals.

Scores of Anishinaabe then began coming to boat landings to exercise their civil rights weeks before the non-tribal fishing season started, to the ire of locals.

Hundreds and thousands of anti-treaty protesters also started going to the boat landings in the late 1980s, complaining that Anishinaabe people were harming the fish populations and hurting tourism in the region.

Confrontations by many soon escalated, and rock-throwing, gunshots, death threats, and racial and sexual taunts soon became common occurrences, according to multiple reports.

Valliere recalls at the time often being on one of two boats on a lake surrounded by thousands of angry protesters on the shore.

Tribal officials said incidents of harassment of spearfishers still occur every season, yet many go unreported.

Those opposed to spearfishing argue it harms the fish populations, but state officials say that’s not true.

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources sets safe harvest amounts for each lake so there is less than a 1-in-40 chance that more than 35% of the adult walleye population will be harvested by tribal and recreational fishermen combined.

“Some people say an extra harvest is given to tribal members, which is not true,” said Todd Ambs, former assistant deputy secretary of the DNR. “Other (non-tribal) anglers have harvested substantially more.”

There are about 500 tribal spearers compared with about 2 million licensed anglers in the state, Ambs said.

Since 1989, the total tribal harvest of walleye in the Ceded Territory averaged about 28,000 a year, according to a joint tribal, state and federal report.

Tribal fisheries on reservations produced more than 15 million walleye eggs in 2018, of which more than 121,000 reached to extended-growth fingerlings and were released into Northwoods lakes.

Tribal officials reported these hatcheries help replenish declining fish populations that may be caused by warming waters, shoreline development and invasive species.

Sign up for the First Nations Wisconsin newsletter Click here to get all of our Indigenous news coverage right in your inbox

Back on the lake

Valliere had special permission from tribal officials to head out on Pokegama Lake with his birchbark canoe and torches this spring. Before setting off, he and the students sang and beat drums to mark the momentous occasion.

After about two hours on the water, Valliere and his apprentice, Lawrence Mann, were unable to catch any fish.

Some spearfishers on the modern boats were able to catch a few, but not nearly as much as normal for the season.

There had still been ice in the water just days earlier and Valliere complained that many of the walleye hadn’t yet started spawning, so there just wasn't any walleye in the shallows to catch.

Despite the lack of catches, he considered the venture a success because it was an important lesson for his students just being out on the water with traditional tools.

“We’re showing we still know how to do it this way,” Valliere said. “We can’t forget our old ways.”

More: Tribal spearfishing is a symbol of Indigenous sovereignty in Wisconsin. Here's why.

More: Tribal spearfishing and representation at the Grammys

Frank Vaisvilas is a Report For America corps member based at the Green Bay Press-Gazette covering Native American issues in Wisconsin. He can be reached at 920-228-0437 or fvaisvilas@gannett.com, or on Twitter at @vaisvilas_frank. Please consider supporting journalism that informs our democracy with a tax-deductible gift to this reporting effort at GreenBayPressGazette.com/RFA.

This article originally appeared on Green Bay Press-Gazette: Ojibwe man sets on tribal spearfishing journey in northern Wisconsin