Tourist trade: In 19th-century Jax, souvenirs ranged from the usual to the unusual

After the disruption and destruction of the Civil War, the following years in Jacksonville were a time of rebuilding. The population exploded, new buildings were erected and expanded, new businesses opened and transportation from the North improved. This economic recovery was aided by the flow of tourists from the North escaping the harsh winters.

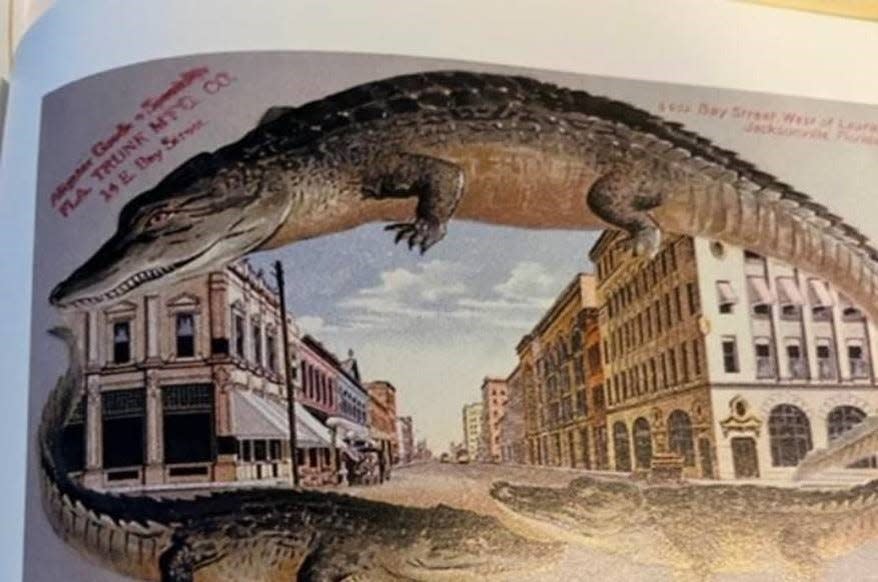

In addition, articles in Harper’s Weekly and other publications extolled the virtues, the beauty of this exotic location and the unique animals such as alligators.

Of course, health benefits of the Sunshine State were also an extremely attractive argument. Come to Florida and be cured of consumption (also known as tuberculosis) — while not mentioning the various fevers, infections and diseases that could kill. All these elements combined into a public relations campaign that resulted in a thriving tourist industry.

Alan Bliss: Jax in the 1920s went from vibrant downtown to gridlocked car town

Letters: DeSantis demeans public education in Florida — and its teachers

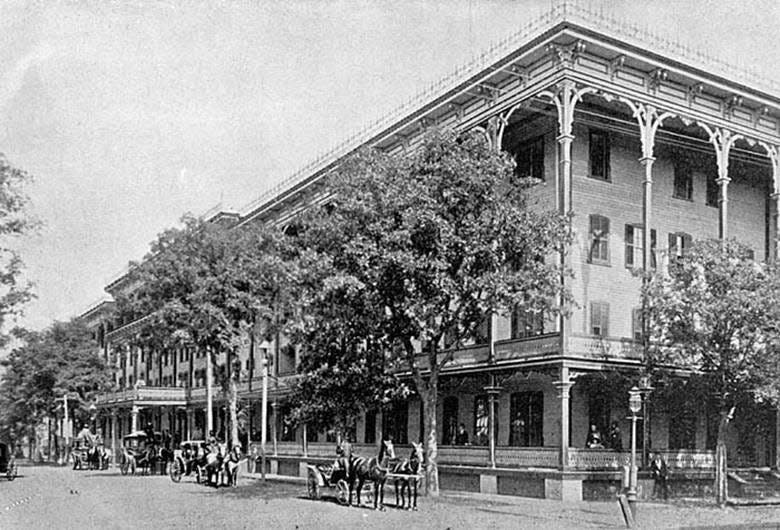

Grand hotels awaited the arrival of these wealthy visitors who had the money and time to explore and reside temporarily in our area. The most elegant was the St. James Hotel, which was the largest in the South, open for guests from December to May. A photo of the St. James was part of an ad in the March 1888 issue of New England Magazine with the expected marketing hyperbole used to entice tourists:

“Unsurpassed in elegance of appointments, embracing a spacious dining room lighted by electric lights; Rooms en-suite with baths; Billiard Parlor lighted by electricity; Electric bells throughout the Hotel; Steam heat; Elevator and a Fine orchestra.”

This centrally located hotel located on the highest ground in the area faced the St. James Park (now James Weldon Johnson Park). What more could a tourist want? It was a well-known destination not only nationally but internationally. The register listed the names of many famous people that once stayed there, with a sprinkle of dukes, counts and lesser personalities.

During this epochal period of 1876-1886, Jacksonville was known as the “Winter City in Summerland.” It was usual for the total number of tourists per season to be printed using the hotel registers and larger boarding houses as the basis for the compilation. T. Frederick Davis wrote that for the 1882-1883 season there were 39,810 visitors while 1885-1886 had the record at 65,193 tourists.

According to Davis, a typical day began with breakfast, followed by shopping after 10 a.m. Bay Street was the hub of activity where well-dressed visitors explored the various curio shops and stores. This was repeated from 3 to 5 p.m. Then the evening festivities were transferred to the hotels with music supplied by various orchestras and bands.

Matt Soergel: Meet Ted Pappas, the Jacksonville architect behind some of the city's iconic buildings

More: Jacksonville's historic Jacobs Jewelers plans move from building with iconic clock

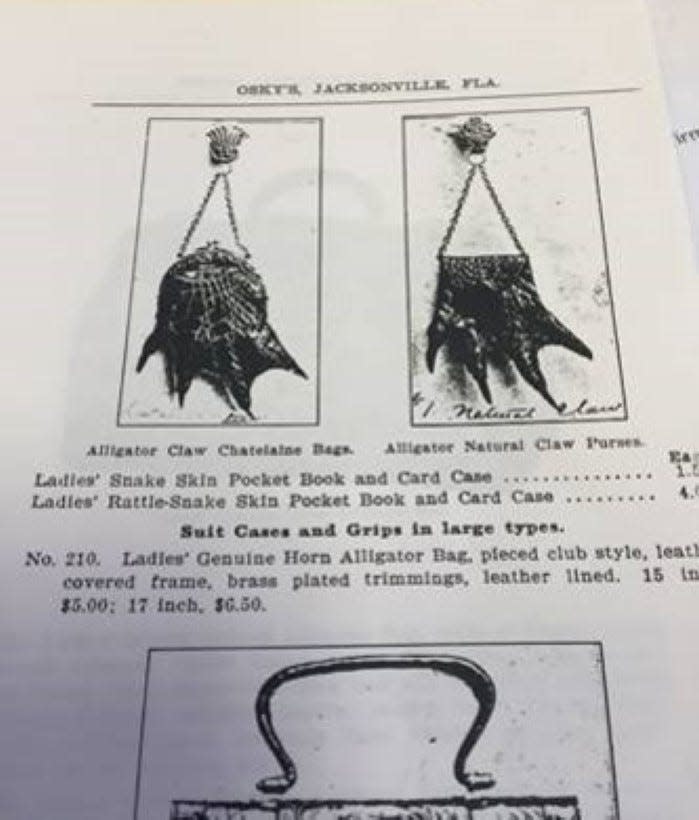

Osky’s Curio Store was one of the largest companies to sell unusual trophies. They began in 1884 and were located on Bay Street until 1955. Their selection was unique and covered many types of items, often with alligator themes. Alligator teeth were used to make jewelry items while canes, spoons, corkscrews, cigarette holders and ink pens were typically engraved with alligator motifs.

One of the most unusual items was an alligator coin purse. In fact, if you tour the Merrill House Museum, an example can be found on the second floor.

An alligator coin purse was small and easily portable, so ladies could purchase one and, returning home, impress her friends with this curio from an exotic animal. This practice was eclipsed later by more fancy and elegant souvenirs, especially after 1890. Poaching of the alligator was eventually outlawed when the reptile faced possible extinction.

This age of souvenirs also included the use of souvenir albums, a more typical form, that provided an accurate representation of the tourist experience. These could be shared with friends back home and, perhaps, spark an interest in a trip of their own. The JHS collection has a variety of these albums that were available to the traveler. Usually with little writing, perhaps just a caption, these views typically focused more on buildings, parks and animals than on people.

These can be found in the JHS rare books collection. Enjoy the journey back in time!

Georgia Pribanic, librarian, Jacksonville Historical Society

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: In 19th-century Jax, souvenirs ranged from usual to unusual