Toxic art: Ohio University professors clean rivers by turning water pollution into paint

MILLFIELD, Ohio — At the back of a once-residential lot on a county road in Athens County, tucked behind the brush, enviromentalists say a toxic problem has been spilling out of the ground for decades.

Each day, one million gallons of bright orange, acidic water pours from a 20-square-mile underground coal mine abandoned in 1964, according to environmentalists at the Appalachian nonprofit Rural Action, Inc. Twenty years later, the mine seal ruptured and began flowing into the property's backyard. The stream, once a small trickle, cuts through the landscape and daily deposits 6,000 pounds of iron oxide into the waterway.

The smell of sulphur hangs thick in the air, even on a cold December day.

"You can imagine what it's like in August," said John Sabraw, an Ohio University art professor.

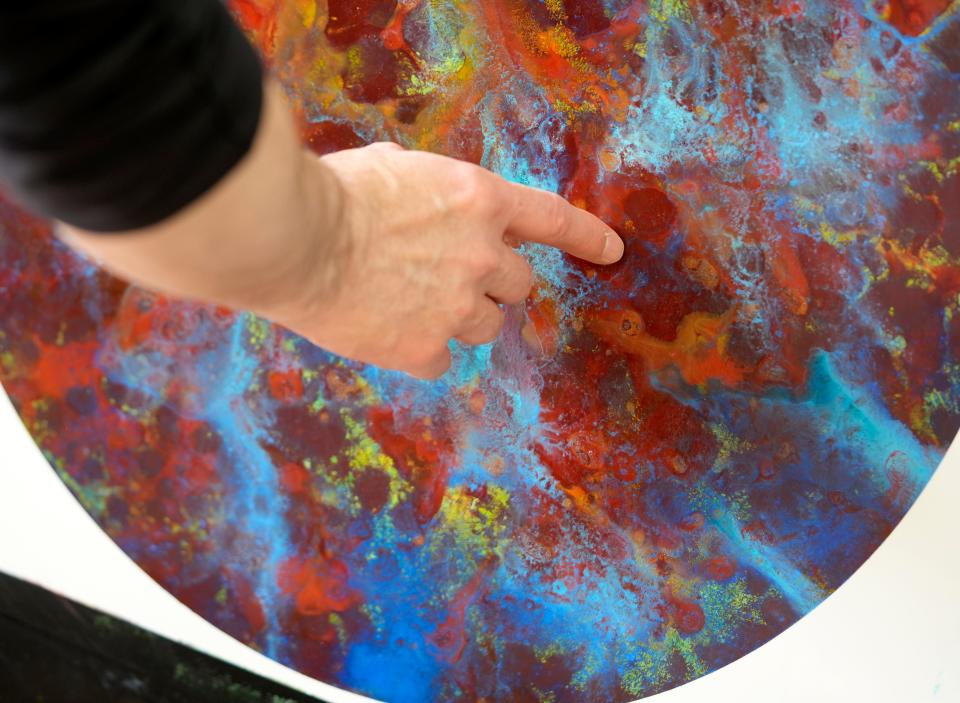

Sabraw sticks his hand down into the creek bed and pulls up a handful of umber-tinted earth. It pops against his teal latex glove.

The problem, called acid mine drainage, is not unique to this property.

Acidic water from the mine flows into Sunday Creek, one of Athens County's most polluted waterways, and eventually into the Hocking River, according to Rural Action. The water itself is clear, but the iron precipitates out once it hits the air and coats the creek beds, making it nearly impossible for aquatic life to thrive.

These orange-stained waterways are an enduring toxic reminder of Appalachia's coal mining legacy, and present an expensive and overwhelming environmental problem, according to Rural Action and state and federal environmental officials.

But Sabraw and Guy Riefler, an environmental engineer and Ohio University chemistry professor, have been working for years on a creative solution to this toxic problem: turning pollution into paint.

Toxic art

True Pigments is a collaboration between Ohio University, Rural Action, Ohio Department of Natural Resources' Division of Mineral Resources Management and the U.S. Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement.

The project began almost 15 years ago as an idea between Sabraw and Riefler. Sabraw had gone on a tour of the acid mine discharge sites at Millfield with other faculty members. That's when he saw the "Halloween pumpkin orange water" flowing before him for the first time.

When Sabraw learned that the stream was orange because of iron oxide — one of the main ingredients in artist's pigments — he filled up a jar with the polluted water and experimented with making paint.

His trials were unsuccessful. Then he met Riefler.

Riefler had also been toying with the idea of pulling iron oxide from the water and turning it into color pigments. Those paints, he figured, could be sold and the funds used to sustain the cleanup project and continue cleaning the water. But he didn’t know enough about paints to determine what would be artist's quality.

Together, the two professors combined their knowledge to create extract the iron oxide from the water pollution and turn it into useable pigments.

Those pigments were then sent to Gamblin, an oil paint manufacturer in Portland, Oregon, to create the first batch of artist-grade paint in 2018. Since then, they've sold close to 10,000 tubes of their pollution paint, called "Reclaimed Earth Colors." The three-tube set, which retails for $42, includes hues of brown ochre, rust red and iron violet, all crafted from the same iron oxide powder. A portion of sales goes back to Sabraw and Riefler to pay students working on the project.

"We will not be working ourselves out of a job"

The project was a success, and the team set their sights on making it sustainable in the long-run.

In January 2020, ODNR awarded $3.5 million to the project in pilot funding to construct a full-scale acid mine drainage water treatment plant at the Millfield site. They purchased a 38-acre hayfield behind the mine drainage site for the project. Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

Like everything that year, Sabraw said the project hit delay after delay after delay.

But progress eventually picked up and the team broke ground on the property earlier this year. Sabraw said the plant is expected to open in 2025.

Acid mine drainage from the seep will be rerouted to the plant, which will neutralize the acidity and collect iron oxide. That water will pump out into an 11-acre wetland that will further purify it before it flows back into the waterways, and the pigment will get sent to Gamblin for processing.

This kind of acid mine drainage treatment isn't new, said Michelle Shively MacIver, Rural Action's director of project development. But other treatment sites haven't found productive uses for the toxic sludge.

Ohio produced about 2.35 billion tons of coal from underground mining between 1800 and 2010. Many of those mines have since polluted more than 1,300 miles of Ohio streams with acid mine drainage, according to ODNR.

In 1977, Congress passed the the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, which required a severance tax on coal sales to pay for clean-up efforts. Pennsylvania and West Virginia have been treating toxic water in their states for decades, but Ohio has not had the same budgets to clean acid mine drainage at scale.

True Pigments paints will help offset the cost of water treatment.

"It's really critical that the treatment would pay for itself," Shively MacIver said.

Shively MacIver said there's been a lot of interest in replicating this kind of water treatment at seeps across the state. There's no shortage of need, she said. The mine beneath the Millfield site could continue flowing for at least 600 years.

"We will not be working ourselves out of a job," she said. "You can't just fix the problem. It will be here in perpetuity."

But the site will be more than just a water treatment plant.

From a knoll overlooking the site, Sabraw sees a future walking trails, interactive sculptures and facility tours. He sees a place where people can gather to learn about this problem and see the solution at work.

Sheridan Hendrix is a higher education reporter for The Columbus Dispatch. Sign up for Extra Credit, her education newsletter, here.

shendrix@dispatch.com

@sheridan120

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Ohio University professors clean rivers by turning pollution into paint