Toxic chemicals leaked under SLO airport for decades. Who is responsible for cleanup?

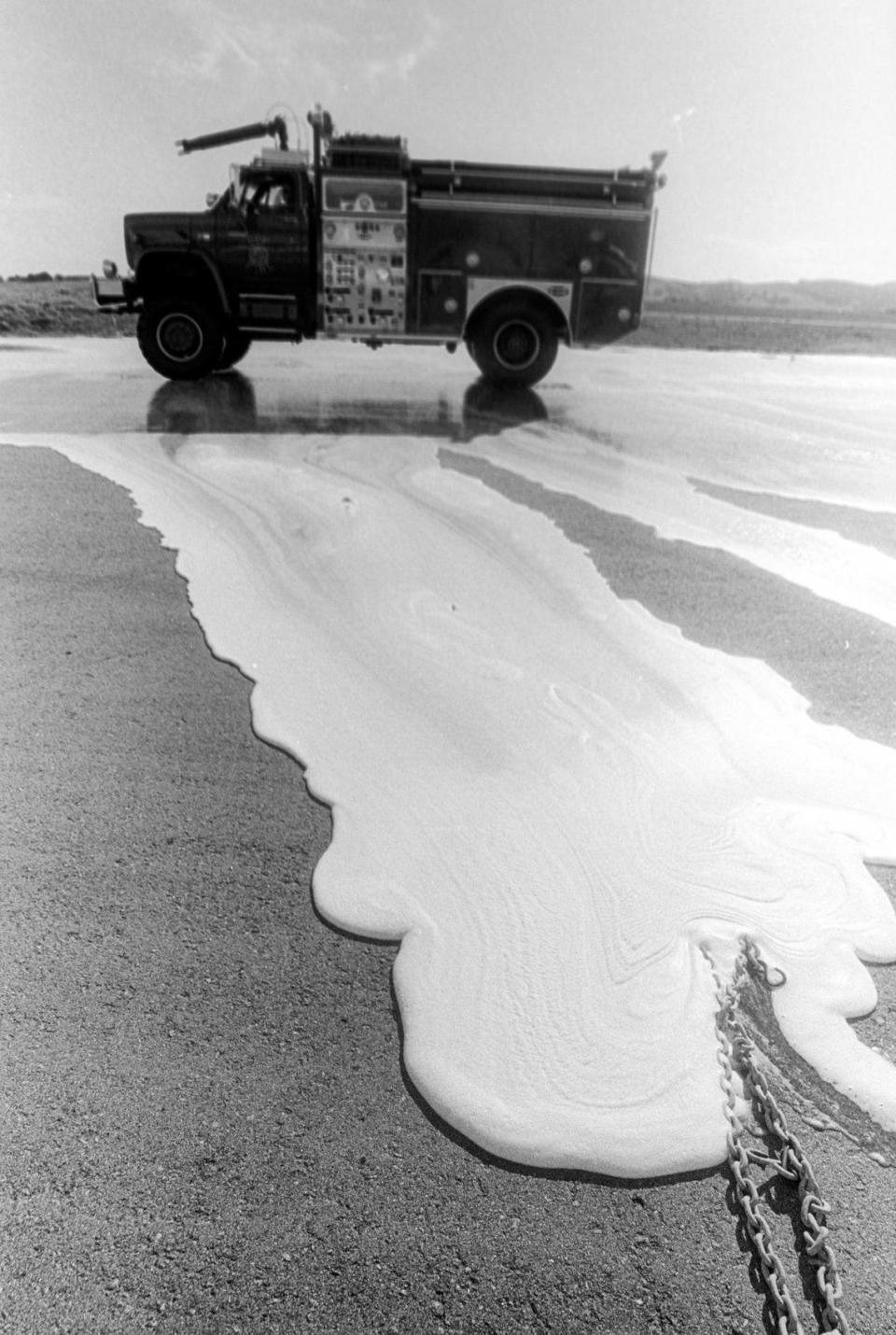

Since the 1970s, firefighters at San Luis Obispo County Regional Airport have trained for potential airplane crashes using a specially designed fire suppressant.

Aqueous film forming foam sprayed from a fire engine can put out petroleum-fueled fires in an instant. It’s particularly good at dousing flames because it contains toxic chemicals known as per- and polyfluorinated substances, or PFAS, which have been linked to a variety of health issues.

Over the decades, those substances gradually trickled from where they were dispensed and leaked into the groundwater under dozens of nearby residents’ homes, infiltrating their water supplies.

In February, the Central Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board issued a draft order to San Luis Obispo County and Cal Fire, proposing they clean up the contaminated groundwater.

Both agencies formally protested the draft order on Friday and argued they shouldn’t be ordered to replace the polluted water. Instead, they point fingers at the Federal Aviation Administration because it required the special foam to be used at the airport.

While the government agencies fight over who is legally responsible, area residents are hoping for a reasonable solution.

“My kids, grandkids and friends visit and expect to use these (household) faucets to drink, brush their teeth and take medications,” Wayne Peterson, a longtime resident of the area with contaminated groundwater, wrote in an April letter to the water board. “It is positively unthinkable to expect that the only safe faucet in the house is a small ... one in the kitchen.”

What are PFAS?

PFAS, like the ones from the firefighting foam, are known as “forever chemicals” because they accumulate over time in the human body.

They have been found to cause a host of health impacts including cancer, liver damage, decreased fertility, increased cholesterol levels and decreased vaccine response in children, according to the U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

The toxic chemicals are so prevalent that most people in the United States have been exposed to PFAS and likely have PFAS in their blood.

They have been used to make nonstick cookware, water-repellent clothing, stain-resistant fabrics and carpets, some cosmetics, and products that resist grease, water and oil, according to the federal toxic substances agency.

There are thousands of chemicals that fall under the PFAS umbrella, and the two that appear most studied are perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS).

PFAS are a relatively newfound class of chemicals, and so there are no established federal or state regulations on how much can be present in drinking water before it’s considered harmful.

In 2016, the Environmental Protection Agency said anything under 70 parts per trillion of PFOS and PFOA in drinking water was safe.

Seven years later, the agency has proposed new regulation limits of 4 parts per trillion. The proposed national primary drinking water regulation — which is expected to be finalized by the end of this year — “will prevent thousands of deaths and reduce tens of thousands of PFAS-attributable illnesses,” according to the EPA.

During investigations beginning in 2019 at the San Luis Obispo airport, PFOS in groundwater were found at levels of 130,000 parts per trillion, or 32,500 times greater than the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s proposed maximum level for drinking water, according to data from the regional water control board.

About 93,000 parts per trillion of PFOA were found at the airport, which is 12,500 times above the EPA’s proposed limit, data from the water board show.

The water board also discovered extremely high levels of PFAS in the wells of dozens of residents near the airport.

In total, 42 wells are polluted with PFAS above healthy levels, according to the water board.

In late 2022, a water board investigation found levels of PFOS in private wells up to 4,500 parts per trillion and 130 parts per trillion for PFOA.

Contamination near SLO airport mixes with other pollution

Many of the wells in the Buckley Road area are also contaminated with trichloroethylene, or TCE.

The TCE, which has been around for decades, was recently found to come from an old asphalt testing lab at 795 Buckley Road.

Because of the TCE contamination in the groundwater, many residents have special filters on their groundwater wells to ensure the water they receive at the tap doesn’t have the harmful chemical. Those filters were installed by the Noll family, who the local water board blamed for the pollution until finding another culprit at 795 Buckley Road.

The Noll family has spent roughly $50,000 each year since 2020 to install those filters and pay for their maintenance.

The county said it has installed small water treatment systems under the kitchen sinks of two households found to not have filters on their groundwater wells that had high amounts of PFAS.

This point-of-use treatment is different from the systems the Nolls installed in that they only treat one spot where residents may be drinking their water. The Nolls’ systems treat the water at the groundwater well, meaning that all water used from that well has been filtered for most harmful chemicals, including TCE and PFAS.

The county said it has spent $2 million since 2019 to pay for the PFAS investigations and water treatment systems in the Buckley Road area.

What can water board order do to clean up groundwater?

So who should pay to clean up and replace the groundwater contaminated by PFAS from the aqueous film forming foam?

The water board’s February draft cleanup and abatement order to San Luis Obispo County, which operates the airport, and Cal Fire, which used the special foam, would require the agencies to fully replace the PFAS-contaminated water with clean water.

In the county’s response to the draft order, attorney Albert Cohen said that the county “fully intends to fulfill its obligations to the public by insuring (sic) that those living and working in the area have drinking water that is safe to use, whether or not the (water board) issues an order, because doing so is consistent with its obligations to its citizens.”

However, the attorney followed that statement with a 15-page letter with 576 pages of attachments arguing neither the county nor Cal Fire is legally responsible for the PFAS contamination — so the water board cannot order them to clean it up.

In its own response letter, an attorney representing Cal Fire noted that California law exempts the two state agencies from any liabilities associated with firefighting activities.

“The draft (order) seeks to impose liability on the county and Cal Fire solely as a result of their providing fire protection services at the airport and their use of AFFF for fire protection and in firefighting equipment and facilities,” attorney Sarah Bell wrote in the letter to the local water board, sent Friday.

State law “grants the county and Cal Fire immunity for such activities and therefore bars the draft (order)’s attempt to impose liability on the county and Cal Fire for providing fire protection services at the airport,” the letter continued.

In its draft order, the water board noted that state policy says “every human being has the right to safe, clean, affordable and accessible water adequate for human consumption, cooking and sanitation purposes.”

Anyone who has been found to discharge a “waste” into drinking water must clean it up, the water board’s draft order said.

However, the county and Cal Fire contend that the firefighting foam wasn’t a “waste.”

“The AFFF was a useful product, not waste,” Cohen wrote in the county’s response letter. “The AFFF used at the airport was a deliberately manufactured and distributed chemical used in accordance with FAA requirements.”

The Federal Aviation Administration has required airports to have the AFFF onsite and ready for use for decades, so the county and Cal Fire argue they had no choice in the matter.

In 2018, Congress directed the FAA to amend its regulations to allow airports to use PFAS-free firefighting foams.

On May 6, the FAA must submit a 120-day transition plan to Congress that would move airports away from using foams that contain PFAS.

“At Congress’s direction, the FAA is developing a transition plan to fluorine-free alternatives, and we urge the agency to complete and submit the plan on time,” U.S. senators from Wisconsin, West Virginia, Michigan and Kansas wrote in a March letter to the FAA. “Delay would be unacceptable, not only to our nation’s airports, but also to the neighboring communities working to address PFAS contamination.”

How do SLO County, Cal Fire want to handle contamination?

San Luis Obispo County and Cal Fire have proposed coming to a voluntary agreement to handle the PFAS pollution.

What that agreement may contain is yet to be decided, and the water board may still choose to move forward with issuing a cleanup and abatement order.

“Cal Fire, like San Luis Obispo County and the water board, takes all reports of any potential water quality issues very seriously,” agency spokesperson Tony Andersen wrote in an email to The Tribune.

Andersen added that Cal Fire “looks forward to continuing solutions-oriented work with area neighbors to find public health solutions that meet the immediate and longer-term drinking water needs of the impacted neighborhood.”

In an April 25 letter to the water board, Courtney Johnson, SLO County’s director of airports, wrote that the county is similarly “committed to addressing public health concerns associated with PFAS.”

To do so, Johnson proposed the county could evaluate possibly installing well-head treatment systems on polluted wells so no PFAS-contaminated water gets into households or onto gardens.

San Luis Obispo County could also evaluate bringing in new, clean water to residents and finding a way to eliminate PFAS from under the airport so it stops leaking into the groundwater, Johnson wrote in her letter.

The water board is currently reviewing public comments it received from residents, the county and Cal Fire regarding the PFAS contamination.

Once it has reviewed and responded to those comments over the next few months, it will likely decide whether to issue a cleanup and abatement order or pursue a voluntary agreement.