Tragedies at 2 Arizona dementia care units leave families shattered, outraged

Anita Ferretti was harmless.

That’s what the assisted living director said after Anita pushed her new roommate, Jennie Fischer.

Anita had arrived at Brookdale North Mesa’s wing for people with dementia just a few weeks prior. Jennie’s daughters almost immediately saw trouble.

They pleaded for Anita to be moved.

Mari Fujita, the director, said there weren’t any open rooms. Yes, Anita pushed Jennie. But Jennie, who was 101, pushed back.

Anita had no television, no chair. Few clothes were in her closet. Jennie’s daughters thought it strange how sparse her part of the room was. They would not learn why for three years.

Jennie’s side of the room had a plush, burgundy recliner and a corkboard adorned with family photographs. An oil painting of a rocky river hung above her bed.

Her closet was bursting with jackets, slacks and shirts she’d embroidered with butterflies.

Anita, who was 79, didn’t speak much. Her chin remained tucked into her neck most of the time, maybe a side effect of her medication. She kept trying to take Jennie’s wheelchair. She slapped at Jennie’s daughter when she tried to intervene.

“I knew she couldn’t hurt me but I knew she could hurt my mother,” said Mary Stanley, Jennie’s daughter.

Anita had spent her life caring for others — before she retired, she was a nurse at the men’s prison in Florence.

The inmates called her Bling Bling, for her sunglasses with crystals on the side.

That Anita would not have hurt Jennie.

Only this Anita, her brain ravaged by dementia for a decade, failed by a system that protects corporations over seniors, could hurt Mary’s mother.

Hundreds of vulnerable seniors, particularly those with dementia, contend with violence at the end of their lives in the very places that promise to keep them safe.

The Arizona Republic spent a year chronicling life inside the state's assisted living facilities and nursing homes and found that state policy protects secrets instead of seniors, benefitting an industry where caregivers are often stretched too thin, inadequately trained and paid too little to keep vulnerable people safe.

Anita moved to Brookdale because her previous facility had kicked her out three weeks prior — after she killed her roommate.

Court and police records, state documents and months of interviews reveal how two assisted living facilities left three families grieving a tragedy.

Anita

Summer, 1973: Anita packed a box of clothes in her Volkswagen and, with her two daughters, drove from Kansas to Arizona to chase the sun and her independence.

Her marriage to a race car driver had flamed out.

Anita got an apartment in Mesa across the street from a school and started waiting tables. By Christmas, both girls had a bicycle and a pair of roller skates.

When her girls were in their early 20s, Anita did something big for herself.

She went to school and eventually became the head nurse at the Scottsdale Memorial Hospital Osborn's neurology department.

She later moved on to a position at the prison.

Taking care of inmates was simply more interesting than working in a hospital, she’d tell her daughter Michele Bixby.

By that time Michele was living in Los Angeles working as a script supervisor. They talked on the phone daily.

Health issues hit Anita in her 60s: a heart attack and two strokes. She was diagnosed with dementia in 2008.

Anita seemed to get along fine, though, so Michele was shocked in 2011 when she visited for a weekend and found mail stacked up and an auction notice on her mom’s house.

Michele took control of Anita’s finances. She took her to a doctor. They learned her dementia had worsened and she’d need a caregiver.

Michele and Anita sat in her car in the parking lot and cried.

“I don’t want to be a burden to you,” Anita said.

“I will always take care of you,” Michele told her.

Over the next seven years, Michele and her son carried Anita through her changing world, a blur of increasingly unfamiliar places and people. Then Michele became the blur. And Anita got scared.

Michele was washing dishes. Anita emerged from her bedroom, squinting.

“Who are you?”

“Mom, I’m your daughter.”

“I don’t know who you are, but you need to leave.”

“Everything’s OK, I’m here to help you. I love you. I want to be here.”

Michele doesn’t remember how she distracted Anita. She just remembers the cleaving heartache she felt as she continued to scrub plates.

Lorazepam kept Anita’s hallucinations and agitation at bay — as long as she had the medication strictly on time. Michele forgot once. She heard about it from the caregiver who stayed with her mom while Michele worked.

Anita had told the caregiver she didn’t know her and that she needed to leave. She grabbed the caregiver’s shirt and ripped it. The caregiver went outside and watched Anita through the window until Michele came home.

Michele hesitantly set out to find an assisted living facility.

“The love that I had for my mom was really immense,” Michele said. “But it grew 100,000-fold as I continued to help her more and more and more as she progressed through this disease.”

When she toured Heritage Village in Mesa, she saw employees mingling with the residents and smelled dinner cooking.

“It looked like they were making a place where they cared about the people,” Michele said.

But it wasn’t just the way things looked: Michele had some specific questions on that tour, according to a legal deposition.

“Do you accept dementia patients?”

“Oh yes.”

“Do you accept dementia patients — dementia patients that can become aggressive?”

“As long as they’re on medication, yes we do.”

And that was why Michele — through tears — trusted Heritage Village with her mom.

Records show the facility would break that trust within two weeks.

Joyce

Joyce Dinet called a taxi. She was going out.

She told the driver to take her to a dance hall and started giving directions. He attempted to follow along. Then she mentioned Bourbon Street.

Bourbon Street?

The man turned around and drove her home.

Joyce recounted the story to her daughter.

Joyce frequented dance halls all over New Orleans in her teens. That was how she met the love of her life, Clarence.

But that was the early 1950s. Now it was 2016. Joyce was 80 and she was in Gilbert, Arizona. Clarence had died in 2012.

Joyce was diagnosed with Lewy body dementia a few months later.

Her daughter Peggy Brown bought a mobile home in Mesa, where the two moved in. Peggy and her sister Denise Marie Dinet took turns caring for their mom. Her son Troy Dinet called his mom every day from Las Vegas and visited over Christmas.

“We took care of mom like she took care of us when we were kids,” Denise said.

Joyce had worked the 4 p.m. to midnight shift at a medical supply packaging factory when they were kids but she made dinner every day before she left — with a little extra. When Denise would come home from school, Joyce would pluck a tomato fresh from the garden and cut it up to look like a blooming flower.

The family knew they needed to find Joyce an assisted living facility in the spring of 2017. She put a TV dinner on a plastic board, stuck it in the oven and started a fire.

Joyce had given them the perfect childhood, one that sounded like the Supremes, Fats Domino and Elvis on vinyl; felt cozy like dancing in the living room; and tasted like pot roast and potatoes, gumbo and fried chicken.

Wherever they moved her, the facility had to be perfect, too.

Joyce’s kids created a list of nearby facilities, vetted their reviews and visited several.

Sometimes they’d walk in and walk right back out. The odor told them they didn’t want their mom there. Other times they’d see unhappy residents.

Their final stop was Heritage Village. Like Anita’s daughter, Joyce’s family was impressed.

The grounds were clean and green, with big houses that lined a cul-de-sac where residents walked around taking in the sunlight.

A piano sat in the living room. Residents mingled and seemed happy.

This was it. In 2017, Peggy and Denise signed. They trusted their mother would be all right.

And she was, for more than two years.

9 days of suffering

Anita moved into Heritage Village around Nov. 25, 2019.

Anita's daughter Michele said staff called her to complain, according to her deposition taken for the lawsuit the Dinet family filed against Heritage Village.

Staff told her Anita got aggressive toward the end of each pill cycle.

Michele told them she normally gave her mom her next dose just before the previous one ran out to avoid any lapses.

She said she didn’t know what her mom would do during a lapse but she feared she could “break out and do something,” so she gave them a doctor’s order authorizing a “gap pill” on Dec. 9.

Anita had a lot working against her that day.

Internally: She’d had two strokes and had dealt with dementia for 11 years.

Strokes increase the likelihood that a person will experience what doctors call “disruptive behaviors,” which are essentially distressing, out-of-character reactions to someone or something. These reactions are also more likely with late-stage dementia, said Dr. Pallavi Joshi, a geriatric psychiatrist at Banner Alzheimer’s Institute.

Chemically: Lorazepam may work quickly to diffuse agitation by temporarily calming anxiety symptoms. But the end of each pill cycle tends to bring greater anxiety and agitation the longer someone uses the drug, Joshi said

And environmentally: Dementia kills brain neurons, plunging people into a frightening new world where loved ones might become strangers and rugs on the floor might appear as bottomless pits.

People with dementia struggle to communicate discomfort and regulate their emotions. Without quality care, they might lash out to defend themselves.

Common triggers include an inability to recognize people around them, moving into a new environment and sharing personal space with strangers.

Unwanted visitors and roommate disputes have caused some of the most severe altercations between assisted living and nursing home residents across Arizona. Most experts interviewed by The Arizona Republic agree that most single residents should have their own rooms.

Nevertheless, facilities put a high price on solo rooms. Not everyone can afford them, and sometimes people don’t think to ask for one. They trust the professionals to know what’s best.

“The cognitive difficulties they face, if not well understood and supported by others, can erode people’s sense of security or control, which can lead to a crisis situation,” said Dr. Allen Power, who authored the book “Dementia Beyond Drugs: Changing the Culture of Care.”

Anita’s crisis struck on Dec. 10, 2019, the day after Michele sent the gap pill authorization.

An employee had skipped Anita’s midnight dose of lorazepam.

Heritage Village called Peggy, Joyce’s daughter, at about 5 a.m.

“Your mom was attacked,” the voice on the line said.

“What do you mean?”

“Peggy, it’s so bad. The paramedics are here and they’re going to take her to the hospital.”

“But what happened?”

“Her arms … her arms … .” The woman handed the phone to a paramedic who said they were taking her to Banner Desert Medical Center.

Peggy hung up, called her sister Denise and met her at the emergency room.

“The best way that I can describe this is like one of the most horrific horror movies that you would see on TV, but the difference was that you’re not watching it on TV,” Denise said. “This is real life, and this is your own mother.”

The sisters found their mom with a black eye, shaking, beet red and moaning. Her forearms were covered in gauze. Blood seeped through.

The skin on Joyce’s arms was peeled off. When nurses redressed Joyce’s bandages, her children saw her tendons and bones.

Peggy called Heritage Village’s manager Courtney Hanna and pleaded for answers.

Hanna said she had no idea what happened, but she had fired a caregiver. Peggy told her she was going to call Adult Protective Services.

Soon after, Peggy walked into her mom’s room at Heritage Village and found it empty.

They threw everything away, Hanna told her.

Family keepsakes like her large framed picture of Jesus and her blue ceramic cross were gone.

And for nine days, Joyce suffered.

Her children were powerless to do anything but watch. Joyce’s body couldn’t tolerate heavy pain medication, so when doctors tried to quell her agony, her face swelled and her blood pressure spiked instead. Sometimes she’d doze off and then awake in a panic, like she was reliving what had happened.

Joyce died on Dec. 19, 2019. Her death was ruled a homicide.

Her children left the hospital as shells of their former selves.

Therapy. Antidepressants. Sleepless nights.

Joyce’s son Troy held onto memories of his mom turning house chores into dance parties as she grooved to the record player with a broom.

But grief is like wearing a weighted vest all the time. Sometimes you get used to it; other times it feels heavier than ever before.

Troy had recurring vivid night terrors where he saw someone attacking his mother and he’d fight to get to her. His spouse would wake him up and tell him it’s OK.

Time does not heal a wound like this.

Broken trust

When Anita's daughter Michele got the call from Heritage Village, she was told only that something happened between her mom and her roommate and both were sent to emergency rooms.

“What do you mean something happened?”

“Well, just go to the hospital and they can help you over there.”

Michele met her mom at Mountain Vista Medical Center. She was told her mother had attacked her roommate, there were “blood injuries” and the other woman had possibly died.

Michele wanted to know more, but no one would talk, she said in a deposition for the Dinet family’s wrongful death suit.

She called Heritage Village. No answer. She tried again. She cleaned the blood from under her mother’s fingernails. And called again. Over the next five days, she called about 20 times.

Finally, she drove over and sat in the lobby.

The woman at the front desk told Michele to leave or they’d call security and possibly the police.

Michele asked for her mother’s clothes. There was a down comforter and pillows and a little rug, too.

“I had everything for my mom. I set her room up beautiful,” Michele said during her deposition.

“When I went in there, it was like nobody ever even lived in there. There was paint dried that had been spilled and was all over the floor. Her little plastic dresser was broken.”

Michele opened the drawers. Half of her mom’s things were missing. The closets were empty.

“It was like my mother and her roommate never existed.”

Michele started driving home, in hysterics.

She called her best friend and left a voicemail. She recounted it during her deposition.

“You will never believe what’s happened. They won’t talk to me — they won’t come out and talk to me. They won’t tell me where my mother’s things are. They won’t tell me what happened to my mother. They won’t tell me what happened to Mrs. Dinet. They won’t tell me anything. Nobody will talk to me and her stuff is missing.”

Michele pulled over on the side of the road and sobbed.

A nightmare come true

It wasn’t until Anita and Joyce’s families hired lawyers that they got a better idea of what happened. They’ve both sued Heritage Village.

A med tech at Heritage Village heard his co-worker shout for help a little after 5 a.m. He followed the call to Anita and Joyce’s room.

Anita was lying in Joyce’s bed, her hands bloody. Joyce was on the floor, bleeding from both arms.

The med tech called 911.

Three Mesa firefighters crammed into the room, which was no bigger than 12-by-12 square feet, maneuvering around a dresser, two single beds and Anita.

Joyce did not speak. She was, as a Mesa Fire and Medical Department employee put it, “battered.”

“Shoulders caved in, balled up, not wanting anybody to touch her, not making eye contact,” Craig McBride, the engineer and paramedic, said in a deposition.

According to the police report, when police arrived, the med tech told an officer he thought Anita had pulled Joyce off the bed. Joyce had thin skin. It tore easily.

An officer determined that Anita didn’t have the culpable mental state for a charge of assault.

At the hospital, a crime scene specialist took photographs of Joyce’s injuries.

Joyce reached out and held his hand.

There were signs leading up to Joyce’s death that Heritage Village had changed from the place her children first saw.

Joyce arrived at the hospital with a significant pressure ulcer at the base of her spine, a telltale sign of neglect.

Denise had also found Joyce with several injuries in recent months. She had called Adult Protective Services but never heard back, according to the police report taken after her mom was injured.

What Denise and her siblings didn’t know was that a state surveyor had also investigated at least 16 complaint allegations against Heritage Village in the few months leading up to Joyce’s death.

The surveyor was unable to substantiate most but issued more than a dozen citations for mistakes found separate from the complaints, including leaving serrated kitchen knives in an unlocked closet that residents could access.

McBride, the Mesa paramedic, would later testify in a deposition for the Dinet family lawsuit that his team frequented Heritage Village more than other assisted living facilities. He guessed over the past several years he was personally called there 10 times a month, sometimes three times a day.

One out of every 10 calls, he estimated, was for assault.

One state surveyor would later remark during a deposition for the Dinet family lawsuit that she thought Heritage Village’s staffing was inadequate most of the time, and that she’d see new employees all the time.

“I felt with a number of complaints, it was just — the whole situation was — was devastating, mind-boggling,” said Deanna Adams, the surveyor. “It was just, I was there so much that — it was difficult.”

She said Heritage Village provided substandard care for Joyce and Anita and the place neglected them.

Exactly what happened is still disputed.

According to Adams’ state report, the med tech didn’t try to give Anita the pill as she usually refused it and his co-worker said not to bother because she’d be getting tired anyway. The co-worker denied having said that.

But in deposition, the med tech said Anita was walking around the dining room and refused to sit to take her medication. He said he tried to convince her several times and sought another employee's help.

That employee told him that if Anita wouldn’t take her medicine he could just let her walk around until she got tired. Then she’d go back to bed and sleep normally.

The employee that skipped the pill was under the impression that Anita was prescribed lorazepam merely to help her sleep. He had never seen Anita’s medication profile that specified the pills were meant to control her agitation.

He never removed the pill from the package.

Sometime after midnight, Anita crashed into crisis mode.

Her daughter wonders what sort of terrifying hallucinations must have been reeling through her mom’s mind that triggered her to injure her roommate and sit still while she cried out for help.

“I put her somewhere that I trusted to be a good, stable, well-rounded put-together program and they couldn’t even do something as simple as give her a pill,” Michele said. “And another woman lost her life and my mother went out of her mind.”

No one knows what time Anita tore Joyce out of bed and how long Joyce lay on the floor waiting for help. The blood on Anita’s hands was dry.

No one knows because — according to the facility manager’s investigation that the Dinets cite in their lawsuit — the hall monitor wasn’t doing his job.

That employee was supposed to check every resident at least once every two hours. He was the one Hanna fired immediately.

Hanna, the facility manager, wrote that the employee didn’t respond “appropriately or immediately” to Joyce’s cries for help.

“Due to the severity and extent of injuries to one resident, it is determined that (he) seriously neglected these particular residents for an extended period of time,” she wrote.

The employee denied that in his deposition, saying he ran his room checks on schedule.

Assisted living caregivers are often stretched thin and insufficiently trained.

Managers are supposed to establish ongoing quality management plans that identify problems and outline methods to fix them. When the state surveyor visited Heritage Village after Anita’s crisis, an employee said they didn’t have the plan as required.

Managers also are supposed to study a potential resident’s record and decide if they’re a good fit before they move in. That hinges on a quality admissions process. Hanna said in her deposition that there was nothing in Anita’s admission paperwork indicating she had a history of combativeness. But Heritage Village never produced that paperwork in court discovery, according to the Dinet family's attorney.

The frontline caregivers often bear the brunt of the fallout when something goes wrong.

Hanna said in her deposition that she didn’t have a clear head when she penned her “quick” investigation. She said she wouldn’t have disciplined the med tech and fired the hall monitor in retrospect, though she never reached out to the man she fired to apologize.

When reached on the phone by The Republic, Hanna hung up.

Heritage Village did not return The Republic’s request for comment. The facility has argued in court that Michele never told staff that her mom had aggressive tendencies and that the facility likely would not have admitted Anita if management knew.

The facility also said Michele and Anita may be to blame for Joyce’s death, according to one of their court filings in the Dinet lawsuit.

Jennie

After the crisis with Joyce, Anita spent nearly three weeks in a geriatric psychiatric ward at Mountain Vista Medical Center.

The hospital transferred Anita to Brookdale North Mesa on Dec. 30, 2019.

Meanwhile, Jennie’s family was trying to adjust to the memory care unit there.

Jennie was lucid — at 101, she’d still crack jokes. But Brookdale, where she’d lived in general assisted living, made her transfer to memory care after she wheeled out the door looking for her daughter, Joey Wilson.

Most of Jennie’s new neighbors milled about speechless with blank stares. Jennie liked conversation and bingo. She was bored and depressed.

Hospice gave Jennie a baby doll with a heartbeat — a common tool that soothes some people with dementia — and Jennie rejected it.

“What the heck is this? Why are you giving me toys?”

Perhaps the biggest drawback of moving into memory care was that she’d have to get a roommate. Her family could afford a single room in general assisted living, but not in the pricier wing that offers more stringent supervision.

About a month after Jennie moved in, Anita did, too.

Jennie's daughters Joey and Mary didn’t know anything about Anita, but they could tell she needed extra care and supervision and they felt Brookdale wasn’t doing anything about that.

Anita had removed her underwear and sat on Jennie’s white, floral comforter. She took Jennie’s wheelchair and pushed it into the hallway. She had pushed Jennie.

On Jan. 22, 2020 — about three weeks after Anita moved in — Jennie’s family got the call.

A Brookdale employee said Anita had pushed Jennie to the floor. Jennie was badly injured and taken to Banner Desert Medical Center.

Joey rushed to the hospital to find her mom in a bed howling. The right side of her face was bruised. Her arm was purple and swollen.

“It hurts!” Jennie yelled.

The doctor told Joey that her mom’s humerus bone had fractured.

It would be tough for her to recover.

Hospital staff put Jennie’s arm in a sling and said they’d done everything they could. She’d need to go back to Brookdale.

Under the fluorescent lights and with the sound of machines beeping and her mother’s moans, Joey’s anger that had compounded every day Brookdale had dismissed her concerns reached its peak.

She called Brookdale and got Fujita, the director, on the phone.

“She will not come back there,” Joey said, nearly yelling. “I don’t know what I’ll do but she will not come back there into that room.”

Within a few hours, what Fujita previously said was impossible suddenly wasn't: Jennie was going to get her own room.

And the family wouldn’t even have to pay extra.

Joey was convinced Brookdale was trying to cover something up.

Fujita did not return The Republic’s requests for comment.

Over the next month, Jennie slipped away.

Jennie’s granddaughter remembers the last thing she said: “I love you more.”

Her kids and her grandkids huddled around her for days, telling stories about Jennie’s life.

The way she taught them Italian when they lived in Naples, Italy, by sitting behind them and translating cartoons into English.

Her foray into organ lessons later in life. The oil paintings she’d craft, each one with a little cardinal painted somewhere on the canvas.

And of course, the lessons her granddaughters would never forget.

“Baciami culo!”

Jennie made sure her grandchildren knew all the Italian curses, and that they enunciated properly.

She also taught them to stick up for themselves, to stash their cash in their bras when they hit the bars and — when the dating scene was harsh — that they didn’t need men to be happy.

On Feb. 21, 2020, their matriarch died.

The entire family was angry.

“They did nothing to protect my mother,” Joey said.

Joey had sent an email to herself to keep track of everything that had gone wrong. Mary had taken videos and pictures. Joey’s husband and her kids urged them to sue Brookdale.

But the weighted vest of grief is exhausting. And a sense of injustice creates barbs that dig in deeper when you try to do anything about them. It hurts to breathe. It hurts to sleep. It hurts to eat.

“I couldn’t face the trauma and sadness and reliving the whole thing over and over again,” Joey said. “I was too fragile. I just needed to wash my hands, walk away from there and get them out of my brain. And forget about Brookdale.”

The sisters tried. But for three years, their unanswered questions haunted them. How did Brookdale let this happen? What was the facility not telling them?

Uncovering the truth: After 2 Arizona assisted living center tragedies, a reporter told families the full story

Searching for answers

Brookdale knew Anita’s history. The facility received her full medical file from the psychiatric hospital that explained why she was admitted there and that she'd been on a routine for her medication, said Michele’s attorney Tammy Wilbon.

But the facility has never had to explain its decisions to Anita and Jennie’s families — even though Anita’s daughter filed a lawsuit against Brookdale because her mom fell several times and developed a pressure injury there.

Brookdale settled with Michele outside of court.

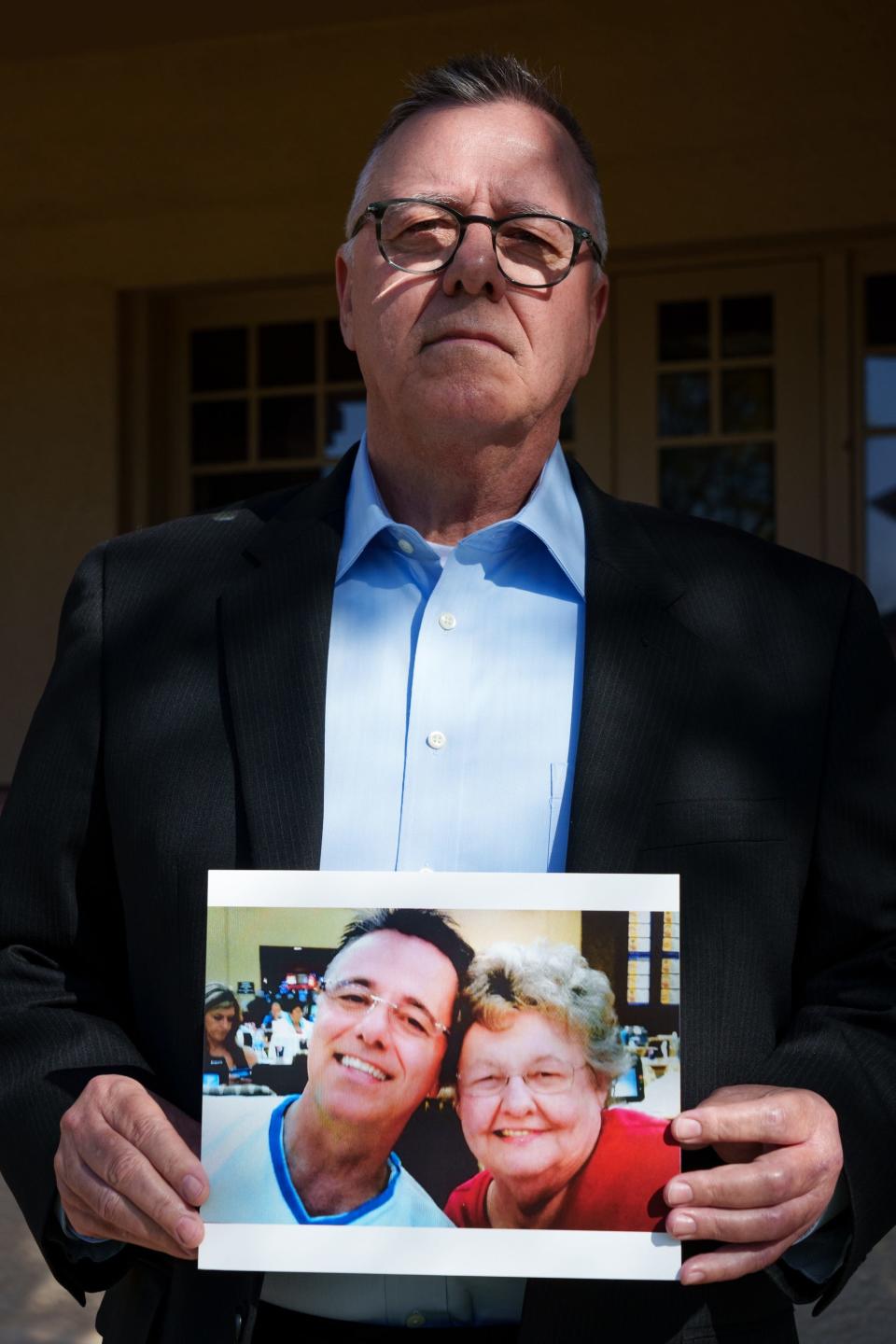

Michele knew nothing about Jennie. And Jennie’s family knew nothing about what had happened to Joyce just weeks prior.

A reporter had to tell them.

Brookdale, when reached by The Republic, said their residents’ “health, safety and well-being is our top priority.”

“I’m sorry, but for privacy and confidentiality reasons, we cannot provide any additional information at this time.”

Facilities can’t divulge information to families about their loved ones’ roommates because of privacy protections. But they are obligated to protect all their residents, and that starts with the admission process, said Martin Solomon, an attorney who has specialized in senior abuse, hospice and nursing home cases for decades.

Facilities should vet each potential resident and make sure they don’t pose a risk to their existing residents. If a new resident has a history of hurting others, the facility shouldn’t move them into a room with a vulnerable person, he said.

Furthermore, if a resident is having issues with a roommate, the facility is obligated to address those issues to keep everyone safe, he said.

While the Dinets’ attorney has argued in a recent court filing that Anita killed Jennie, Michele’s attorney told The Republic that there isn’t enough evidence to come to that conclusion.

Though an employee witnessed the first push, no one witnessed the second. Jennie told Brookdale staff that Anita pushed her. And if Anita did push Jennie, while fractures can trigger health declines among seniors, the fall itself did not kill her, Wilbon said.

The medical examiner listed Jennie’s broken arm at the end of a long array of fatal ailments.

Jennie’s official cause of death was “complications of Alzheimer's dementia with a contributory cause of death of hypertensive and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, emphysema and a recent right humerus fracture."

Jennie's daughter Mary wants to get back in the fight against Brookdale but authorities have already dismissed her mom's case.

Assisted living facilities have to call the police or Adult Protective Services when residents get injured.

But Jennie and Anita’s clash was not reported to police when it happened. The medical examiner called the police after removing Jennie’s body a month after the incident.

Anita had died of COVID-19 by the time a detective was able to get records from the facility. The detective noted in August 2020 — seven months after Jennie died — that he had not heard from staff about the information he’d requested. He was told the manager he'd talked to no longer worked there so he left a message for her successor.

The new director asked for a warrant. His warrant sought — among staffing information — all records associated with Jennie and Anita, not limited to their medical files.

Brookdale only turned over medical records.

Arizona requires assisted living facilities to document and investigate suspected abuse, neglect or exploitation. The report is supposed to outline management actions to prevent the issue from happening again.

But the only mention he found about the incident was a single note in Jennie’s file.

Anita was dead and the records he’d waited for revealed no additional information about Jennie’s fall, he noted.

He closed the case.

Brookdale never had to face any sort of reckoning.

A former health department spokesperson previously told The Republic that the state investigated and found nothing wrong. But after his last day working there, a different spokesperson said he was incorrect.

There was no complaint. And no investigation.

Mary still wanted to try to get some information.

On a recent afternoon, Mary sat on her couch with her daughter on a nearby chair, her chihuahua on one side and her Lab-German shepherd by her feet, and she dialed Brookdale for the first time in years.

“Thank you for calling Brookdale North Mesa, how can I help you?”

“Hi, my name is Mary Stanley and I’m calling about who can I talk to to obtain an incident report on my mom?”

“Um … I don’t know if it’s going to be on file, but let me send you over to the nurse to see if she can look it up.”

“This is for Jennie Fischer, that’s my mother.”

The employee put her on hold for two minutes.

He returned to tell her the nurse would have to “dig deep” for records and call her back.

No one called back.

When Mary called again, she was told that the incident report she wanted was internal and she was not allowed to see it.

Mary thought back to that solo room her mother was given after her injury, with no extra charge.

“That was to keep our mouths shut,” she said.

Brookdale couldn’t keep what happened quiet forever.

This story was updated to reflect new information from the Department of Health Services about whether a complaint and investigation happened at Brookdale North Mesa.

Reach Caitlin McGlade at caitlin.mcglade@arizonarepublic.com. Follow her on X, formerly Twitter, @caitmcglade.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Tragedies at Arizona assisted living centers stir outrage