After tragedy and amid protests, Sybrina Fulton seeks her own political path in Miami

Sybrina Fulton wants to clarify something: she isn’t flat-out against defunding police — but she isn’t necessarily for it, either.

Fulton, thrust into national prominence eight years ago when a neighborhood watchman gunned down her unarmed teenage son, Trayvon Martin, said in an interview with the Miami Herald that she has become more receptive to the idea of shifting funds from law enforcement toward social services after speaking against it last month during a Miami-Dade candidates forum.

“I understand a little more clearly now, they’re not saying when you call 911 that nobody’s coming,” said Fulton, whose father was a police officer.

Fulton said her initial opinion — which disappointed some activists engaged in street protests around Miami — has changed after learning more about the concept. “I would say that’s something that would be on the list,” she said. “But I would look at other measures first.”

As she runs against a former prosecutor for a Miami-Dade County Commission seat representing Florida’s largest majority-Black city, Fulton’s candidacy has been elevated by a wave of social justice street protests. But she isn’t exactly making her candidacy about the movement.

The 54-year-old former county Housing Authority employee says she sees her campaign as an extension of the frustration with government voiced by people pouring onto the street. She attended the Houston funeral of George Floyd after his death at the hands of Minneapolis police ignited protests around the country. She is seen by Miami activists as something of a matriarch to the modern movement, and she says her desire to run for local office came in April 2019 as an epiphany during a speech at an event by Rev. Al Sharpton’s National Action Network.

But Fulton does not have a position on Florida’s cash bail system. She shares a friendship and alliance with former Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton that makes some progressive protesters squeamish. And while she is critical of the Miami-Dade state attorney’s handling of fatal police shootings., she says she doesn’t believe police brutality is a central issue for the voters who will decide her Aug. 18 race against Miami Gardens Mayor Oliver Gilbert.

“This area doesn’t have a problem with police officers shooting our residents,” Fulton said of the district, which includes Miami Gardens and Opa-locka, during a June 11 forum hosted by the Miami Foundation. “We need to address retaliation, the gangs, those types of things.”

Fulton’s announcement last month that she’d officially made the August ballot was covered by NPR, CBS, New York Post, HuffPost, BET and CNN. Thousands of people from around the country have flooded her campaign with small-dollar donations.

But with mail ballots going out in about two weeks, Fulton has not sought to turn her campaign into a referendum on policing and criminal justice. The opportunity is there: Gilbert is a former prosecutor who grappled early in his tenure with accusations and lawsuits saying that the young city’s newly established police force had enacted arrest quotas and aggressive tactics described by Miami-Dade’s public defender in a 2014 Fusion interview as “New York City stop-and-frisk on steroids.”

Fulton, who graduated from the same Miami Gardens high school as Gilbert, offered no specific criticisms of the mayor during an interview, saying only that she has “a lot” of issues with his tenure.

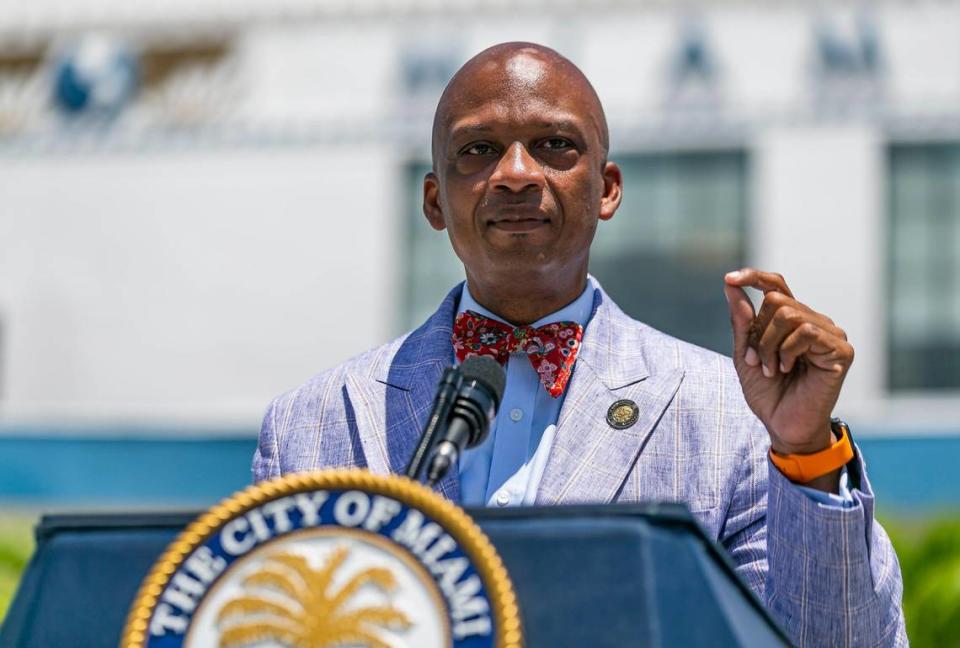

Gilbert, meanwhile, says he’s pushed for accountability and more community policing since becoming mayor in 2012 after four years as a councilman, and talks of the importance of the protests sweeping the country in demand of police reforms.

“I think people around the country are definitely paying more attention to this race because of the protests and the Black Lives Matter movement and Sybrina’s candidacy,” Gilbert said in an interview. “I think the kinds of issues we encounter in a Black city are reflected in our national self-examination of inequities in American society. But ultimately, all politics is local.”

Both Gilbert and Fulton list transportation, housing and the economy on their list of priorities, all staples of a local, non-partisan election.

Fulton has also stopped short of embracing in full the ambitions of the organizations leading Miami’s protests, such as The Dream Defenders, a prominent activist group formed in the wake of Trayvon’s 2012 death with the goal of overhauling what it believes to be a racist and oppressive criminal justice system. She said she remains “in contact” and forever indebted to the Dream Defenders and Black Lives Matter, another criminal justice activist organization founded in response to the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s killer. But she says, “I can’t tell you I know everything they’re doing.”

“I have my own foundation, and we’re not going to agree on everything. That’s OK,” said Fulton, president of the Trayvon Martin Foundation, based out of Florida Memorial University in Miami Gardens. “I never want to be in a position where I’m saying something just because it sounds good.”

That’s not to say that Fulton has avoided the protests, or ducked the spotlight. She has been a notable presence at several marches, including a rally organized by clergy downtown. When she spoke to the Miami Herald for an extended interview recently, she was packing up a car to drive south to Liberty City outside her district for another march that ended with a barbecue and voter registration drive.

“Politicians aren’t helping enough. I want to put that faith, hope back into peoples’ minds,” said Fulton, who wore fatigues and a red Trayvon Martin face mask. “I want them to see me as themselves and say ‘She will fight for us. She’s concerned about us. She will put people over politics, people over profits.’ I want them to know that this is about them trusting me.”

Miami-Dade Corrections Officer Markeven Williams, among the crowd of protesters that afternoon, said seeing Fulton continue to call for racial equality after her son’s death “makes the movement stronger.”

“It lets me know that she hasn’t given up,” said Williams, 32. “She knows where we’ve come from and she lives that life.”

But the protests — and efforts to steer the movement toward the ballot box — haven’t noticeably spilled over into the race to replace term-limited County Commissioner Barbara Jordan as the elected representative of the predominately Black communities in northern Miami-Dade County. Nailah Summers, a co-founder and spokeswoman for the Dream Defenders, said the organization hasn’t gotten involved in Fulton’s race, even if “it will hurt if she doesn’t win.”

Strategists and veteran politicians familiar with campaigns in Miami’s Black community question whether Fulton’s candidacy will catch on with the deep-rooted voters who dominate low-turnout summer elections like the one that will decide her race. But her campaign appears to have caught fire with supporters across the country. Over the first two weeks of June, nearly 5,000 donations — most of the $15 and $20 variety — poured into her campaign coffers from people living in California, Texas, Massachusetts and New York. She raised nearly $160,000 in badly needed campaign cash during the period, nearly doubling her total haul to $366,000.

Even so, Gilbert, who was first appointed to the Miami Gardens City Council in 2008 with the help of a nomination by then-Mayor Shirley Gibson, a retired county police officer, has raised nearly $800,000 so far. He has Jordan’s endorsement.

Gilbert speaks with admiration of Fulton’s perseverance. “What she and her family went through was tragic, and the world was watching, and I think her strength in the face of that tragedy is admirable,” he said.

Gilbert said he supports the job Miami-Dade State Attorney Katherine Fernandez Rundle has done as state attorney and says he doesn’t support shifting resources away from law enforcement. But he characterized the criminal justice system as “punitive,” and said he supports “bail reform” — another cause popularized by the Black Lives Matter movement — because “you shouldn’t be sitting in jail because you’re poor.”

Gilbert said Miami Gardens has enacted police reforms since he took over, and in an interview noted that half of his city’s police department is now half-Black after leaders began recruiting from its own neighborhoods and surrounding communities.

“I want the officers policing with and for the people they grew up with, the people they go to church with, the people they conduct business with,” he said, adding that he worries about “over-policing” residential neighborhoods. “I said if someone is charged with a misdemeanor marijuana offense, why not put them in a diversion program rather than put them into the system? The system is forever. Officers have a lot of discretion. Everyone doesn’t have to go to jail.”

Tangela Sears, an activist who has known Fulton for years and marched with her recently in downtown Miami, told the Miami Herald she isn’t sure her national profile will help her earn votes. “National support is one thing, but they can’t vote in this election,” said Sears, whose son was shot and killed several years ago in Tallahassee by a man later declared not guilty in a jury trial. “The people in Miami Gardens seem to be happy.”

There is recent precedent for mothers turning grief into political activism, and turning that activism into success at the ballot box. Lucy McBath, whose son, Jordan Davis, was murdered in 2012 at a gas station by a man angered by the volume of the music coming from Davis’ car, won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in Georgia in 2018.

Fulton said in a recent interview that winning isn’t the only barometer for success, positing that Lesley McSpadden, the mother of slain teenager Michael Brown — killed while unarmed by a police officer in 2014 — succeeded in promoting her cause despite a losing bid last year for Ferguson, Mo., city council.

Fulton, though, said she believes she has a good chance to win.

“I don’t think of myself as underdog,” she said. “I’m a winner. I think I have a good chance.”

Miami Herald staff writer Martin Vassolo contributed to this report.