Trail of Tears to a Tribal Nations Summit: The White House's role in Native American history

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Before there was a White House, Native American tribes such as the Nacotchtank and Patawomeke lived in the Potomac Valley region for more than 10,000 years, part of an East Coast network linked by interconnected waterways.

Captain John Smith came in 1608 to a region dotted with villages near modern day-Washington, D.C., that had developed sophisticated trade relationships, agricultural innovations and advanced tools.

Within seven decades, all of this land had been claimed by colonists who settled Maryland and Virginia – including a prime location on the Potomac River that would become the new nation’s capital city. As we observe National Native American Heritage Month, it is fitting to consider how the White House that was built on these tribal lands became central to the history that followed.

Early attempts to meet with Native Americans

Even before the executive mansion was completed, George Washington met with Cherokee chiefs and their wives, beginning a long tradition of presidential meetings with Native American delegations who would soon be coming to the White House. During the War of 1812, President James Madison invited delegations from Midwestern tribes, hoping to head off alliances with the British.

In the 1830s, Cherokee leaders John Ross and John Ridge came to the White House for a series of unsuccessful meetings with President Andrew Jackson after the state of Georgia passed legislation to expel them from their lands.

Trail of Tears: A tragic history

Jackson and his successor Martin Van Buren deployed federal forces to remove up to 16,000 Cherokees from the southeastern United States on what became known as the Trail of Tears, along with tens of thousands of Muscogee, Seminole, Chickasaw and Choctaw Indians who were forced to move west of the Mississippi River.

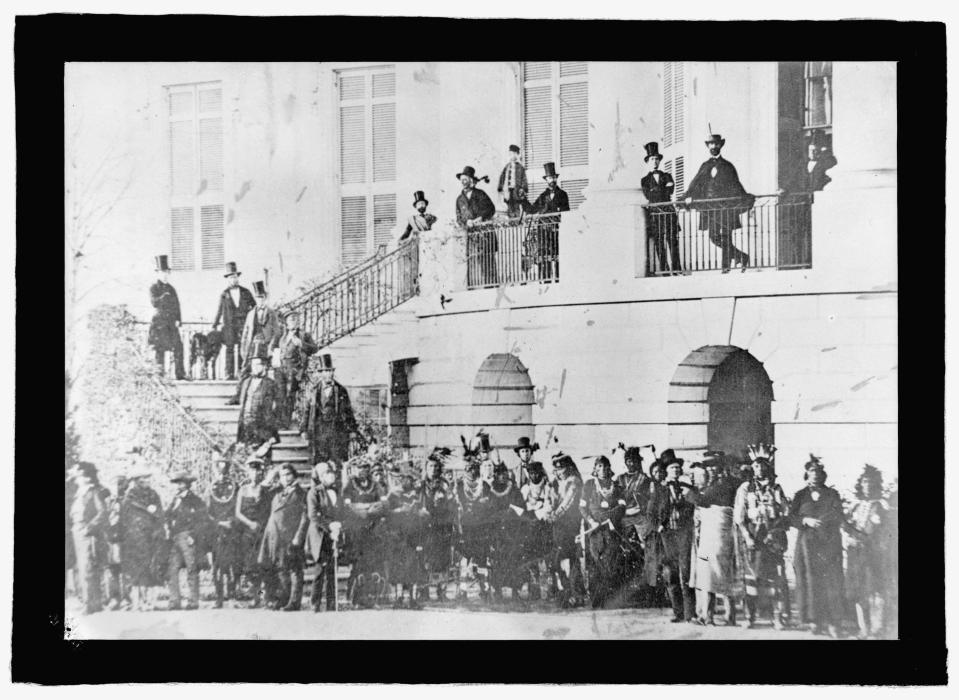

During the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln invited leaders from the Apache, Arapaho, Caddo, Cheyenne, Comanche and Kiowa nations to the White House to seek alliances and prevent their support of the Confederacy. He also signed legislation allowing settlers to further displace Native Americans while vowing to clean up corruption in the government’s own system for managing relations with Native peoples.

Opinion alerts: Get columns from your favorite columnists + expert analysis on top issues, delivered straight to your device through the USA TODAY app. Don't have the app? Download it for free from your app store.

After the war, a delegation of Teton Sioux visited President Ulysses Grant to discuss the prospectors and settlers flooding into Sioux and Cheyenne Indian lands when gold was discovered. Grant could not persuade them to leave their homeland, and the Teton Sioux and Northern Cheyenne peoples were dispersed when the federal government confiscated the Black Hills.

In the decades that followed, as the U.S. government sought assimilation by breaking up tribal lands and standardizing farming and ranching practices, two-thirds of the remaining Native American land was taken.

Presidential portraits: Roosevelt, Lincoln and the Obamas. The stories behind iconic presidential portraits.

An evolving relationship

By the 1920s, the U.S. encounter with Native Americans was evolving, in ways that could be seen at the White House. President Calvin Coolidge, who claimed he was descended from Native Americans, frequently hosted them at the White House and posed for public photographs.

When Coolidge brought in the Committee of One Hundred, an advisory council of experts and activists, he was so impressed by remarks from Cherokee poet Ruth Muskrat that he invited her into the White House for a private lunch.

“We want to become citizens of the United States, and to have our share in the building of this great nation that we love. But we want also to preserve the best that is in our own civilization,” Muskrat said. “No one can find our solution for us but ourselves.”

Coolidge later became the first sitting president to visit a Native American reservation, where he was inducted as a member of the Lakota tribe in the same Black Hills that had been the epicenter of the 19th century wars.

As Native Americans increasingly protested their sovereignty status and pressure to assimilate, President John F. Kennedy met with the National Congress of American Indians at the White House in March 1963.

“A challenge for us all,” Kennedy said, is “making sure that the American Indians have every chance to develop their lives in the way that best suits their customs and traditions and interests.”

White House tours resume: The White House is fully open for tours. Why Jacqueline Kennedy deserves some credit.

The upcoming Tribal Nations Summit

President Richard Nixon brought Taos Pueblo tribe leaders to the White House in 1970 as part of his work with Native American groups to return lands, settle claims against the federal government and change the government’s focus on assimilating Native Americans.

Given this difficult history, it’s no surprise that many Native Americans view the White House as a place to amplify their concerns, like the caravan that came during the 1976 bicentennial to demand greater self-determination and land rights, or the 2017 Native Nations Rise march protesting the construction of the Dakota Access pipeline.

Native Americans have come to the White House for more than two centuries for many purposes, where they have frequently been treated as obstacles to expansion or in need of civilizing. When they return this month for a Tribal Nations Summit, to a White House built on tribal lands, it will be to discuss the federal government’s treaty and trust obligations to their peoples.

Stewart D. McLaurin is a member of the USA TODAY Board of Contributors and president of the White House Historical Association, a private nonprofit, nonpartisan organization founded by first lady Jacqueline Kennedy in 1961 to privately fund maintaining the museum standard of the White House and to provide publications and programs on White House history.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: The White House's role in Indigenous history: An evolving relationship