Trajectory of a mall’s life: DeSoto Square Mall, once the ‘place to be’ in Manatee, fades to oblivion

As a teenager in the mid-1980s, Iris Pitnikoss worked at Ritz Camera, the film and photo equipment store in Manatee County’s DeSoto Square Mall.

She sold cameras – professional devices like Nikons and Kodaks, as well as smaller models like Fujifilms, which were more for everyday candid snaps. The store even had a machine where photo negatives could be processed in under an hour.

“We used to get really busy in there, have a lot of rolls of film to print, and this was one-hour photo,” Pitnikoss said. “I always loved Nikon cameras so it was fun to sell those.”

Part two: How did the DeSoto Square Mall fall so hard? The Great Recession and the internet

When she finished work, her boyfriend at the time, Daryl Solodar, would sometimes be waiting for her in the mall hallways with a bouquet of carnations. He would drive more than an hour from his home in Clearwater just to see her after work.

Eventually, Daryl asked her to marry him. Iris Pitnikoss became Iris Solodar. At their wedding, the manager of Ritz Camera was the photographer. Back then, the whole staff at the store had a passion for taking pictures – including Iris, who went on to a career in sports photography.

Subscribers: Attorney: DeSoto Square Mall closing in Bradenton was ‘long anticipated’

Malls like DeSoto Square were a focal point of daily life

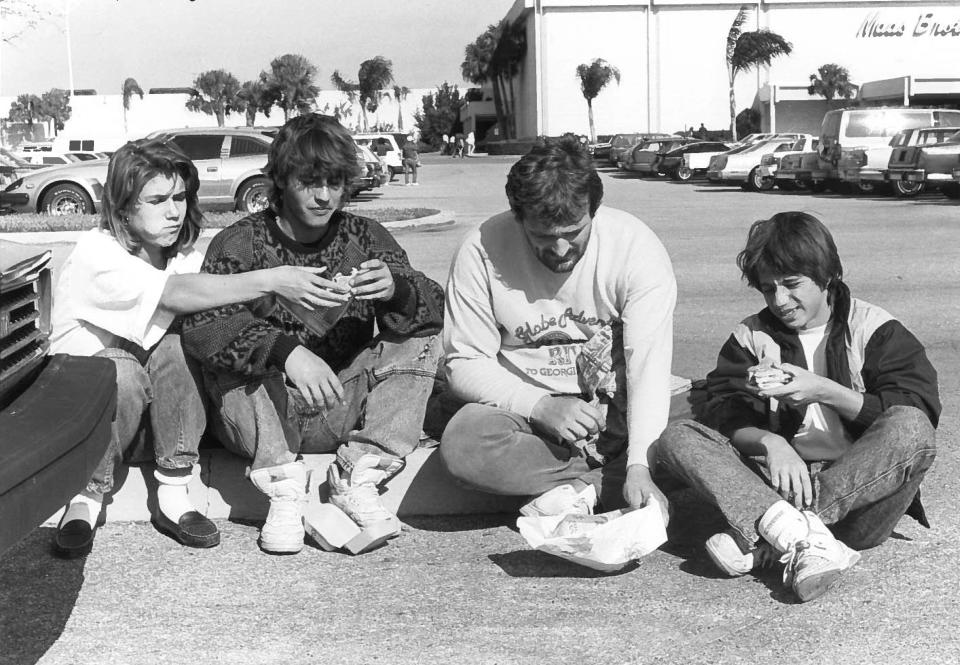

Stories like Solodar’s are typical of people who came of age in the latter half of the 20th century. Malls like DeSoto Square were a focal point of daily life. More than just shopping places, they were cultural touchstones, pivotal to growing up, economic mobility, leisure and social interaction.

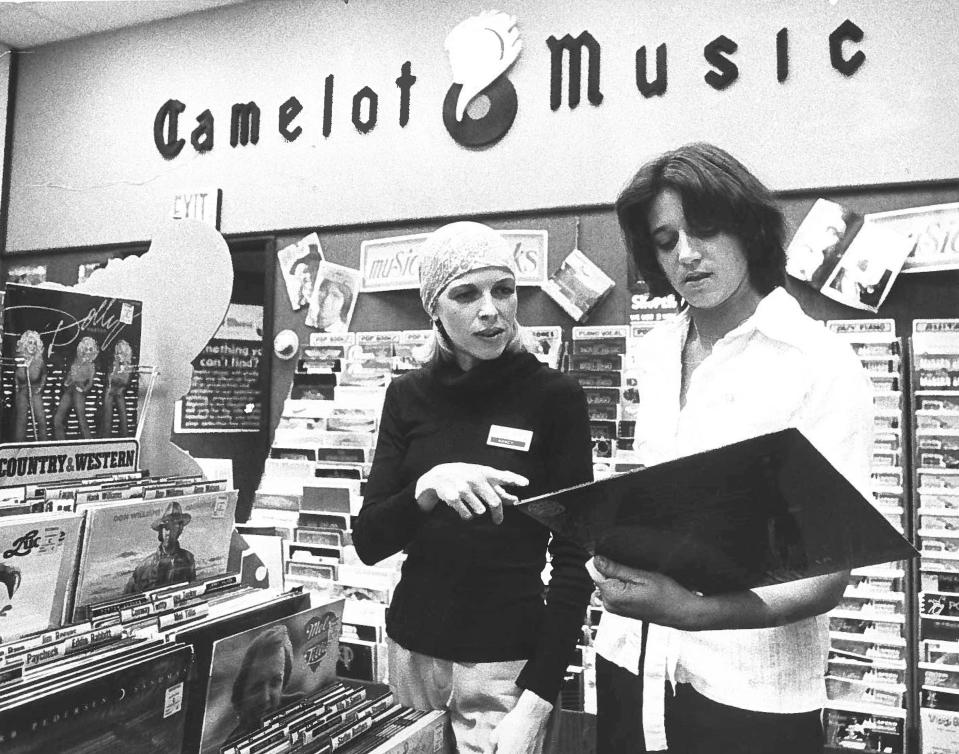

Sure, you could go there to buy things. Stores like the Vogue Shop, Lane Bryant, Waldenbooks and Camelot Music at DeSoto Square always had the latest in fashion and entertainment. But it was more than that.

The mall had a movie theater, an arcade, places to eat and plenty of space for events like high school proms and science fairs, home decor expos, political discussions and celebrity visits. It was such a community focal point Ronald Reagan held a rally there when he campaigned for president in 1976.

As important as it was to Bradenton, however, the DeSoto Square Mall eventually struggled. From the day it opened in 1973 until the early 21st century when things started to really go downhill, DeSoto Square Mall traced the arc of the rise and demise of malls as a center of U.S. commerce and culture.

It officially closed as a mall on April 30, 2021.

Previous coverage:

DeSoto Square Mall lender issues credit bid for control of site

For subscribers: Bradenton's DeSoto Square Mall set to be auctioned off again

DeSoto Square Mall, Manatee County’s only indoor shopping center, to close permanently

Shifting dynamics

DeSoto Square Mall was built during an era that could be referred to as the great American shopping mall boom.

The widespread use of the car and the creation of the interstate highway system that followed the end of World War II resulted in population growth in newly formed suburban areas by mostly white families, Tom Fisher, director and Minnesota Design Chair at the University of Minnesota’s College of Design, said.

Austrian architect Victor Gruen, who had emigrated to the U.S. during the rise of Nazi Germany, saw that this new suburban population would need shopping closer to where they lived.

“In the suburbs, there were a few stores in the middle of seas of parking lots. (Gruen) felt that the suburbs deserved to have a type of pedestrian environment, similar to a downtown,” Fisher said. “He wanted to get people out of their cars and walking, in the same way that he experienced when he was in Europe as a young man.”

The first mall in the U.S., Southdale Center in Edina, Minnesota, opened in 1956, designed by Gruen. Although it was an enclosed, indoor center, it also had touches that alluded to the outdoors, like a bird aviary, a fish pond and a cafe.

“He was basically trying to replicate being out on a real street but doing it in an enclosed, air-conditioned place,” Fisher said.

It was Gruen who came up with the idea of having competing department stores on either end of the shopping center. This was designed to attract more people, give them choices and encourage them to walk down the mall’s hallways and see other, smaller tenants along the way, Fisher said.

Gruen’s mall design would go on to be replicated by other architects and developers throughout the next few decades.

Over the course of 30 years, there was an enormous wave of mall construction across suburbia.

“What happened in many communities is a mall was built in close proximity to the exit of a U.S. highway or an intersection which was newly built or developed, and it was wildly successful,” Mark A. Cohen, director of retail studies at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Business, said.

With malls also came the rise of the specialty store industry, and of chain stores, Cohen said. They were created to fill out the smaller spaces inside of malls between the anchor stores.

“Some of the specialty stores came from downtown, but many of them were newly formed national chains, like The Limited, for example,” he said.

As a result, once-booming downtown areas started to hollow out. It didn’t happen all at once – like the suburban mall boom, it occurred slowly and steadily, over the course of about 30 years in the mid-to-late 20th century, Cohen said. Many cities had more than one mall on different sides of town – and at the time, they were all successful.

“The local department store saw their business decline, because they were doing business in the mall, or they actually closed their downtown stores. And the mom-and-pops, or local stores that had typically done business downtown either found a way to move to the mall or they went out of business,” Cohen said.

News of a mall coming to the Bradenton area spread in the early 1970s. In November 1971, an entity called Bradenton Mall Corporation purchased about 100 acres at U.S. 301 and Cortez Road for $1.6 million from 32 various landowners.

Bradenton city officials, including Mayor A.K. Leach, worried about how a mall outside of city limits would impact downtown merchants. But, Leach said, merchants had already been through a lot, including the Great Depression, a 1926 hurricane and “the onslaught of the Mediterranean fruit fly.”

“I think they’ll weather this storm, too,” Leach told the Herald-Tribune in 1972.

But gradually, downtown Bradenton did become less of a retail center and more of a professional services district. And it wasn’t just Bradenton that experienced this change.

“It became logical for stores to locate new branches near where people were living, and also which were easily accessible by car,” Steve Kirn, a retired lecturer from the University of Florida, said. “So the fundamental design of the shopping mall, with a cluster of stores in the middle, surrounded by an ocean of parking places, because people now had cars and they could drive there: ‘Woohoo, this is exciting.’”

And if there was one person who knew how to capitalize on that excitement, it was the builder of the DeSoto Square Mall.

DeSoto conquers Bradenton

His name was Edward J. DeBartolo. He was born in Youngstown, Ohio, in 1909 to an Italian family. He was known to work 15 hours a day during the week, 10-12 hours on Saturdays and seven hours on Sundays, according to the New York Times.

In 1972, the year before DeSoto Square opened, the Edward J. DeBartolo Corporation built 4,231,670 square feet of retail shopping center space in the U.S. That same year, the company had an estimated $300 million in assets; projects in the pipeline at the time were expected to bump that total up to $450 million.

Like any good developer, DeBartolo did his homework. And that homework gave him a particular affinity for Florida. He told the New York Times Magazine in 1973 that population and age studies his company did in the Sunshine State proved that it was a lot more than just a place for retirees.

“Boy, this state is really something,” he told the Times magazine. “It’s jumping right out of its skin. Land prices are high, but I’ve got news for you: They’re going to get a hell of a lot higher. Honest to god, in my opinion, this crazy Florida is in its infancy. You hear me? In its INFANCY.”

Stan Rutstein, a Manatee County-based commercial real estate broker with decades of experience in the retail industry, said that DeBartolo was the kind of developer who would tell you what you were doing instead of ask.

“We would go in the conference room with Mr. DeBartolo. He would have in front of him – eight cities, seven cities, where he’s going to build a mall. And you would say, ‘it’s great, we love it, we’ll take this city, that city and this city.’ And he’d say, ‘Oh, no no no, we don’t work that way,’” Rutstein said. “‘Unless you take this, you don’t get that.’”

The mall that would become DeSoto Square was not one of DeBartolo’s busiest, most high-profile properties, Rutstein said. It was more like the kind of place where you’d have to open a store if you also wanted a spot in one of his shinier developments.

As the corporation name indicates, the shopping center’s original name was Bradenton Mall, despite the fact that it wasn’t technically located in Bradenton. The idea to call it “DeSoto Square” came from Richard Turner, the president of the Manatee County Conquistadore organization, who thought giving the mall a name with historical significance would draw more attention to the area’s annual DeSoto Celebration.

Building suspense

As DeSoto Square’s opening approached, the DeBartolo Corporation started to release the names of the retailers that would fill out its state-of-the-art concourses.

First, on the west end of the property, there would be a 99,946-square-foot Sears store with a full-service cafeteria, a 20,000-square-foot 16-bay automotive service center and a covered, drive-thru package pickup department, according to a press release from the company in 1972 kept by the Manatee County Historical Records Library.

On the opposite end would be J.C. Penney Co., and in the middle anchor spot, which was visible to customers when they walked through the front doors of the mall, there would be a Maas Brothers.

At the center point of the mall in front of Maas Brothers, there would be a huge colonnade courtyard with two circular fountains that, “when shut off, will be converted to a stage area for use in fashion shows and other activities,” the DeBartolo Corporation said in its press release.

In a story published Aug. 14, a day before the mall’s doors opened to the public for the first time, the Bradenton Herald, didn’t hold back the accolades.

“Manatee County is proud of its new shopping center – every bit as much as the Edward J. DeBartolo Corporation, its builder, and those who own the businesses which will operate within,” the Herald wrote. “The pride is showing.”

The opening was grand

Half of the mall’s tenants, including JCPenney, were still under construction on opening day. But that didn’t stop 10,000 people from wanting to be among the first to check out Manatee County’s hottest – and most anticipated – new attraction.

The mall’s hostesses, who had been training for this day, directed customers to the stores they were looking for. Local law enforcement ensured a steady flow of traffic through the mall’s 2,469 parking spaces, which were filled to capacity all day.

And greeting visitors at the main entrance, in its six-foot tall, bronze glory, was a 200-pound statue of Hernando de Soto, the Spanish conquistador. The statue, designed by Miami artist Bob Stoetzer, was flanked by six ships, in full sail, hanging from the ceiling above the conquistador’s head to further illustrate his conquest.

Aug. 15 may have been the mall’s first day, but some tenants, like the DeSoto Square branch of Manatee Federal Savings and Loan, had opened a few days prior. The bank branch was two stories tall, with a staircase on either side of the ground floor that connected in the middle, Carolyn Keller, the bank’s branch manager on opening day, said.

Keller, now retired and still living in Manatee County, recalls the excitement.

“All of the stores were getting ready to open and making sure everything was perfect. There were free coffee and cookies and all kinds of things,” Keller said.

Over the next few months, more retailers continued to fill out the mall’s fleet of tenants, Manatee County historical records show. There was Nello’s Men’s Store, which started in Sarasota in the late 1940s as a shoe repair shop. There was the Ranch clothing store, the World Bazaar and the mall’s McDonald’s.

And then, in late November, the Montgomery-Roberts department store opened to the public, with company president Hurdis Chestnut on hand for the ribbon cutting.

JCPenney, the last of the mall’s three pre-planned anchors, officially opened in January 1974. Store manager John Mitk, vice president and regional manager Stan Putman, district manager Jim McCall and Miss Florida Ellen Meade were on hand to cut the ribbon.

One of the highlights of the early days of DeSoto Square was the Piccadilly Cafeteria. The cafeteria concept was popular around the time of the shopping mall boom, before food courts took over as the norm.

A typical Piccadilly cafeteria in the 1970s and 1980s would be about 10,000 square feet, Rick Fuchs, who was vice president of real estate for the company starting in 1982, said. The DeSoto Square Mall location was about 11,000 square feet, according to Herald-Tribune archives.

Customers would get a tray and walk along the cafeteria line, where they could peek at the hot food and ask the employee standing behind the glass to please scoop some out for them.

New traditions

Piccadilly had more than 1,500 of its own secret recipes, Fuchs said – the cafeterias would have eight to ten hot entrees, up to ten different varieties of salad and tons of dessert options, all at the same time.

The concept really took off in the south, Fuchs said, and it was sort of a Sunday tradition for people to go to church and then eat at the cafeteria for dinner. Their biggest day of the year, sales wise, was Mother’s Day.

“We had chicken entrees, beef entrees, seafood entrees, and everything was cooked from scratch. We had our own recipes that we kept secret, or tried to,” he said.

Rutstein operated a Casual Corner store at DeSoto Square for about a decade. The mall was just like any other mall, he said. It was nothing special – in fact, his Casual Corner store there did not perform particularly well.

But it was still a mall, and as malls were the most successful retail model of the time, it attracted major department stores and tenants.

The mall’s fourth anchor, a two-story, 100,000-square-foot Belk-Lindsey department store, opened in 1979, historical records show. An expansion added room for eight new stores totaling 5,534 square feet and two more movie theaters, bumping the mall’s total up to six. By early 1979, there were rumors that Burdine’s would join as the mall’s fifth anchor.

But DeSoto Square was a lot more than department stores, cafeterias, movie theaters and even places to grab a quick bite.

In December 1973, its first holiday season, DeSoto Square hosted a clown show to celebrate Ringling Brothers, Barnum and Bailey Circus’ 104th year world premiere, according to historical records. In February 1974, the mall hosted an art show featuring works from 25 professional artists, including landscapes, seascapes, florals, oil on canvas and much, much more.

The following month, a petting zoo came to the mall, and a goat named Charlie pulled kids around in a carriage.

DeSoto Square was so much the center of events that in 1977, mall general manager Brian Hennesey took on the role of director of promotions on top of his management duties.

“Did you ever really stop to think about the frequency and diversification of the promotional events at DeSoto Square Mall?” the Bradenton Herald asked on Aug. 18, 1977. “Very few people realize the magnitude of some of these events, and the efforts required to maintain these programs in a timely fashion.”

Hennesey told the Herald at the time that the mall Merchants Association coordinated an estimated 80 events per year.

Some, like boat shows and art exhibits, went off without a hitch. But others, like Santa’s arrival in 1976, had to be rearranged. That year, Santa was scheduled to parachute into the mall’s parking lot to make his grand arrival for the holiday season. But the sky was so overcast that the plane he was in had to return to the airport; Santa reached the mall with a police car escort.

Reagan’s big visit came in 1976 as part of a campaign swing through Florida. His visit was a big deal, even though the sound system went out near the end of his speech, according to Herald-Tribune archives.

Keller, the branch manager of Manatee Federal Savings and Loan, said that the bank inside the mall was used as a sort of Reagan team headquarters during the candidate’s visit. She said she exchanged pleasantries with him and found him to be very nice.

“He autographed a business card for me,” she said. “There was a lot of excitement when things like that happened.”

At the mall’s 10th anniversary in October 1983, the Bradenton Herald reflected on its impact. Retail stores had been replaced by business offices and residential developments. Having a mall with a variety of stores in a centralized location made shopping easier for residents. And with the vast amount of entertainment options available, the mall had become the modern version of the old town square.

“Ten years ago, DeSoto Square, like thousands of other shopping malls across the nation, sprouted up because it boasted ‘one-stop shopping,’ free parking and shelter from inclement weather,” the Herald wrote. “But malls offered more than just convenience. They provided a common meeting place for communities and offered entertainment such as music, craft shows, car exhibits and consumer product demonstrations.”

Food holds court

Despite DeSoto Square’s popularity in Bradenton, it was not one of DeBartolo’s high-profile properties, Rutstein said.

“The income levels weren’t there, the size of the community wasn’t there, the anchors were not quite what we would like, but we had no choice,” Rutstein said. “That mall was built because the developer wanted to build the mall. That’s why today, you hear the expression, ‘There are so many A malls, B malls and C malls,’ because most of the those malls were built on what was referred to as tertiary real estate – third-rate locations, and you can’t make lemonade out of lemons.”

The biggest challenge malls faced since their inception came in the mid-1990s, when Amazon.com was invented by Jeff Bezos in Seattle. Amazon started out as an online seller of books, but quickly expanded to things like video games, toys, home improvement items and consumer electronics.

“A lot of the senior retail executives – some of whom I worked with and for, village idiots, one and all – sat in their cloistered boardrooms 25 years ago and said, ‘well, this internet thing is a fad. Anybody can sell books and music but nobody will buy anything consequential via the internet,’” Cohen said.

Slowly, but surely, the internet started to chip away at the market share once dominated by shopping malls and department stores, Cohen said. And as a result, retailers had to look for ways to make cuts.

At first, those cuts might have been subtle. Maybe the merchandise at a store would be a little off one week, or the store would seem a little dustier than usual because of cuts to janitorial staff. But eventually, those things started to add up.

“For decades the customer was more or less handcuffed to that location. Now the handcuffs are gone, because the internet has become a portal for an enormous array of customers into anything and everything from anywhere,” Cohen said.

DeBartolo died in 1994 at the age of 85. In 1996, his company was acquired for $1.5 billion by Simon Property Group. Simon, founded in Indianapolis, Indiana, in 1993, was a competitor of the DeBartolo company.

The merger of its parent company didn’t seem to make much of an impact on the day-to-day operations or the shopper side of DeSoto Square. There was still lots of fun to be had at the mall in the 1990s.

Christmas was always a big deal at DeSoto Square, several people interviewed said. In 1993, Christmas celebrations consisted of bells, drums and Victorian bears, who ice skated near JCPenney. Anyone who rode the mall’s express train received a free coloring book of the DeSoto Square Bear Cub Family during a Santa visit, newspaper historical records show. Shoppers could also get their presents wrapped for free by presenting their receipts to the gift wrap booth near the mall’s Lerner store.

In 1994, a 15-foot high sandcastle was constructed in the concourse of the mall using 60 tons of sand.

By the mid-1990s, however, shoppers did notice something was missing. By then, food courts, where multiple restaurant tenants would operate on the perimeter of a giant cafeteria, were becoming an expected part of the shopping mall experience. The Gulf Coast Factory Shops in Ellenton had one, with a Chinese restaurant, a soups, sandwiches and salads spot, a Taco Bell outlet and a Gloria Jean’s Gourmet Coffee.

But despite talk about adding a food court in the late 1980s, DeSoto Square didn’t have one.

In July 1996, the Bradenton Herald reported that ownership would invest $2.7 million into building a 388-seat food court and a new entrance into the Sears wing of the mall. The food court, called Port O’Call, would have a tropical theme with several restaurant slots – including a spot for longstanding tenant McDonalds.

By early 1997, the food court was open with two spots occupied – one for McDonalds and one for Charley’s Steakery. Planned tenants were Barnie’s Coffee and Tea Company, Bourbon Street Cajun food, Nature’s Table, Sbarro and Chick-fil-A. Arthur Treacher’s Seafood Grille also relocated from its existing restaurant near Dillards, which had replaced Belk-Lindsey as an anchor in 1992.

Some existing mall restaurants opted not to move to the centralized eating spot, including Mr. Dunderbak’s Bavarian Pantry near JCPenney. The mall also had a branch of legendary Sarasota ice cream maker Big Olaf Creamery.

Mall in transition

Business was good. DeSoto Square was at 91% occupancy, and the movie theater, then under the Cobb name, was due to be expanded from six screens to 18, according to historical newspaper records. When Port O’Call held its official grand opening in April 1997, Dawn Wells, who played Mary Ann on the television show “Gilligan’s Island,” was there to judge a “Gilligan’s Island” castaway look-alike contest.

Even though the mall had been open for about 25 years, the experience of going there for a kid in Bradenton was pretty similar to what it had been in 1973.

Dakota Duffina, 24, went there a lot between 2003 to 2010 because of the skate park that was across the street. Before that, her mom told her about taking her older siblings, who were 10 and 13 years older than her, to the mall during Halloween for trick-or-treating. She got her hair cut at Regis Hairstyles at DeSoto Square for about 11 years.

“They would have everything decked out for Christmas, and it would be so, so busy in there. That was the time period where they had the carousel in the food court, so that was really cool,” Duffina said.

But even during those good days, the cracks were starting to show. DeSoto Square was going for more discount and service-oriented stores by 2005.

In May 2003, just a few months shy of its 30-year anniversary, Piccadilly Cafeteria at DeSoto Square closed.

This was the beginning of the end for DeSoto Square Mall. But its death didn’t happen quietly, slowly or subtly. In order to get to where it ended up on April 30, DeSoto Square Mall would have to be pummeled by several other unrelenting retail storms.

Support local journalism with a digital subscription to the Herald Tribune.

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: DeSoto Square Mall in Bradenton: Remembering the mall in its original iteration