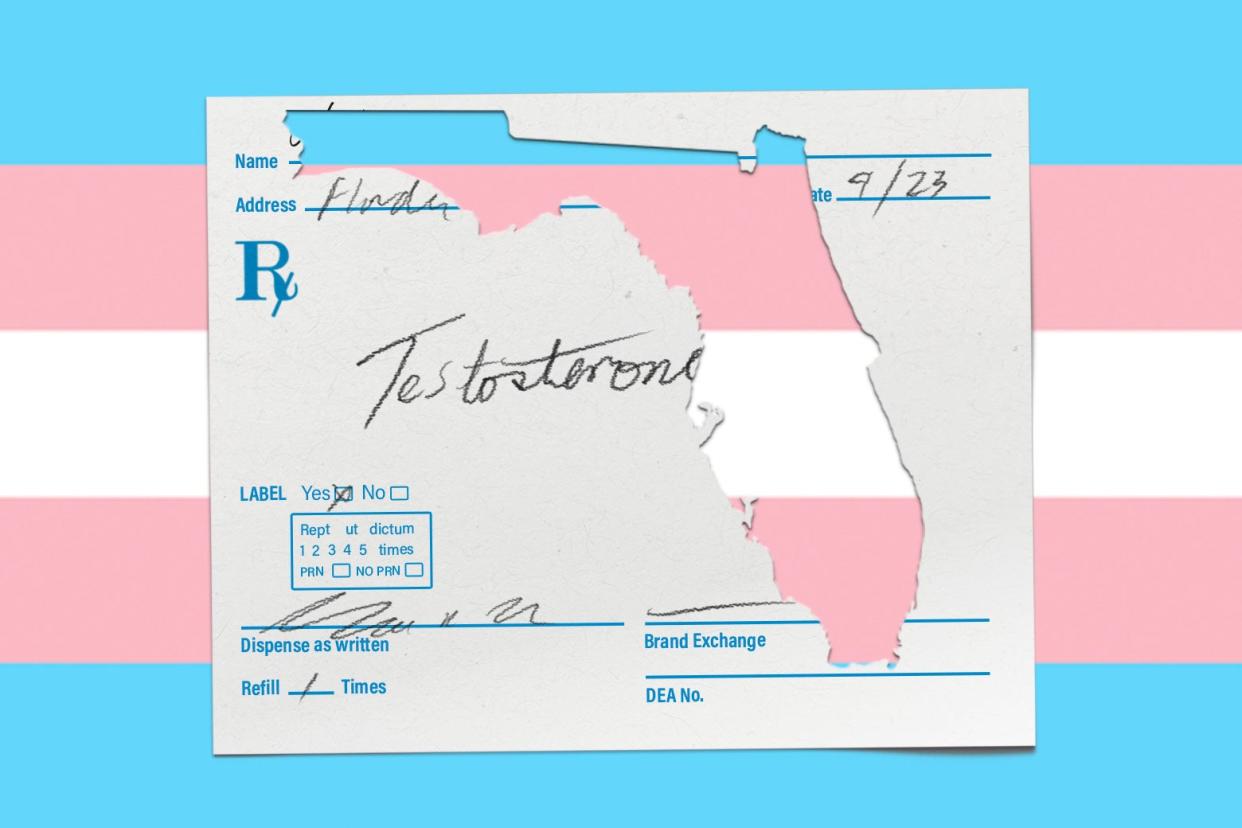

Trans Health Care Is Severely Restricted in Florida. People Are Left With Dangerous Solutions.

If he isn’t able to refill his testosterone prescription in the next two weeks, Vash Addams tells me, he’s worried that he’s going to be forced to break the law. Testosterone is classified as a Schedule 3 controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, and possession of the synthetic version of the sex hormone without a doctor’s prescription is a Class 1 misdemeanor, punishable by a sentence of up to a year in prison and potentially a fine of up to $2,500 on the first offense.

When Addams first spoke to me over the phone from his home in Tampa, Florida, he said he doesn’t want to risk possible jail time, with a wife who needs him and a young son to support. But as a trans man in desperate need of the medication he’s been taking regularly since 2016, he felt he had no choice.

“I have maybe two doses of my testosterone left—two half-doses,” Addams said in an Aug. 26 interview. “If I can’t get it, I may have to turn to the black market. I had a hysterectomy about six years ago, so my body creates no hormones on its own. It’s getting really serious for me, and I know other people in a very similar situation. Nobody’s got good answers right now.”

Three months after Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a bill restricting access to the vast majority of trans medical care in Florida, trans people across the state are being driven toward impossible choices as they grapple with the fallout. SB 254 was advertised by its supporters as protecting youth from treatments they claimed were experimental by making it a felony to provide hormone replacement therapy or puberty blockers to trans minors.

The law was partially enjoined following a scathing ruling from U.S. District Judge Robert Hinkle on June 6, in which he claimed that SB 254 will cause “irreparable harm” to trans minors, calling the statute “an exercise in politics, not good medicine.” But that injunction, for now, allows only the three trans youth who signed on to a lawsuit against SB 254 to access gender-affirming care. Those medications remain out of reach for other trans patients in Florida under the age of 18.

And despite the alleged focus on safeguarding youth, the law also targets trans adults. For trans patients of all ages, SB 254 requires that prescriptions for hormones like testosterone and estrogen be administered solely by a doctor—not any other kind of qualified medical professional. It also severely restricts the use of telehealth: Although a patient may continue to see a doctor virtually after an initial in-person visit, new prescriptions cannot be issued via telehealth, nor can a patient who is now no longer allowed to see a nurse practitioner simply switch to seeing a doctor via telehealth.

These aspects of the bill may seem somewhat neutral when taken at face value: Trans adults need to go to an M.D.’s office to get their medicine—so what? But banning these routes to specialized health care is draconian and unprecedented, especially when you consider that telehealth and medical care administered by nurse practitioners constitute a major segment of the modern U.S. health care system. A 2022 survey of the national workforce of nurse practitioners found that 70 percent reported administering primary care, and 2021 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicated that 37 percent of adults utilize telehealth to access medical care.

It can be difficult to get an appointment with a doctor, for any reason, in a timely manner. Telehealth and nurse practitioners help expand patient access to care, whether it’s for dermatology, mental health care, or many other common patient needs. These routes to care are especially important for trans patients: An estimated 80 percent of prescriptions for gender-affirming medications are written by nurse practitioners, according to data from the Orlando-based LGBTQ+ clinic Spektrum. Folx, an LGBTQ+ telehealth service, estimated that 1,500 of its patients were based in Florida before the law passed.

The new law meant that Addams was no longer able to see his regular provider, a nurse practitioner, after its implementation on May 17. He had been rationing his testosterone for months in preparation for the worst-case scenario: the last of his supply running out.

Addams had been hoping to avoid that scenario, but due to a miscommunication between his pharmacy and his former medical provider, he wasn’t able to get his prescription refilled before DeSantis signed the bill. He had to be referred to a new doctor in his network and couldn’t get an in-person appointment until Aug. 15. At the time of our first interview, he still hadn’t received the medication due to a series of delays, which have included testosterone being out of stock at his pharmacy.

Rather than taking his normal dose of 0.6 milliliters of testosterone every week, Addams has been taking 0.3 milliliters every two or three weeks. He said the severe reduction in his medication has resulted in fatigue and intense headaches, during which it feels as if “half my head’s being squeezed in a vise and something’s being stabbed into my eye.” He has also noticed a rapid decrease in muscle mass and lies awake at night in fear that his health could deteriorate further if he runs out of testosterone entirely.

“I had the muscle tone of a 25-to-30-year-old guy,” he said. “Now I’ve got the muscle tone of maybe a 50-year-old guy. I’ve got a son that turns 9 in a couple of days, and I can’t run around and keep up with him like I could when I had my testosterone. It’s made a lot of things really difficult.”

Countless other trans Floridians are similarly finding themselves with few good options now that SB 254 has decimated access to gender-affirming medical treatments in their state. The law has had a chilling effect on the kinds of care that are still allowed. Every LGBTQ+ person I spoke to for this story claimed that only a handful of providers in the entire state are currently administering transition treatment, as many doctors have stopped providing trans health care altogether out of fear of being targeted by state officials. The wait for an appointment is commonly monthslong for doctors who are still treating trans patients, due to the overwhelming demand. In order to access medication, many trans people have responded by traveling out of state, such as driving to neighboring Georgia, where the state’s trans medical care ban does not include restrictions on health care for trans adults.

One option for trans Floridians able to get to the Georgia border is QueerMed, a telehealth service operating in 25 states. Founder Izzy Lowell, whose background as a practitioner is in family medicine, confirmed that once trans patients are over that line, they can pull into a parking lot and log on to their appointment from their car. But she noted that parents with trans minor children have to travel a bit farther: to South Carolina, the only state in the entire southeastern U.S. that doesn’t yet restrict gender-affirming care for minors. (Lawmakers in South Carolina advanced a trans youth medical care ban out of subcommittee in March, along party lines, but the proposal has yet to become law.)

“Florida has been by far the most challenging state we cover because they put so many restrictions in place and they keep changing the current restrictions so it’s really hard to follow,” Lowell said. “We have grant funding to help people cover travel costs to get anywhere out of Florida, literally, to see us. For teens, we’re doing the same thing: For anybody who can’t get care because of the laws, we’re helping them get out of the state of Florida in order to see us for a televisit, and then people already on hormones can continue.”

Several advocacy groups have begun offering grants to ensure that trans people and their families can afford the added expense of leaving the state to access care, if they need to do so. In May, the Campaign for Southern Equality expanded its then-2-month-old Southern Trans Youth Emergency Project to allow people over the age of 18 to apply for $500 grants to subsidize the cost of gas money, plane tickets, and other forms of assistance. The group, which is based in Asheville, North Carolina, currently operates the grant program in 11 Southern states, and has been able to support more than 200 trans adults in Florida to date. That support includes connecting grantees and others in need to doctors outside Florida willing to provide them treatment.

But some advocates said that it’s been a struggle to keep up with the sheer volume of requests for medical support they’re receiving. Morgan Mayfaire, executive director of the Miami-based resource group TransSOCIAL, said that his organization “only has enough funding to help a fraction of the amount of trans people in the state” through its own grant program. With an estimated 94,900 trans people, Florida has the second-largest population of trans adults in the country, according to a 2022 report from the Williams Institute, a think tank at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The organizations will help cover the cost of medicines themselves if they’re not covered by insurance, but paying for travel itself becomes complicated when the grantee is a trans minor whose parents have to go with them. “When it’s someone who’s young, we have to fly the whole family,” Mayfaire said. “That means hotel stay; it means everything.” He estimates that flying out an entire family costs thousands of dollars per trip.

While organizations scramble to help, many fear that some trans Floridians will slip through the cracks as the state continues to tighten restrictions on trans health care. In late July, the Florida Boards of Medicine and Osteopathic Medicine finalized new consent forms that patients, even those who are currently accessing medication, will be required to sign in order to continue receiving medical treatment. The documents claim that gender-affirming care is purely “speculative” and is based upon “limited, poor-quality research,” despite the fact that leading groups like the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics support gender-affirming medicine for both trans youth and adults.

If the state plans to keep increasing barriers to trans people getting their health care from a licensed professional, some might turn to potentially risky solutions like self-medication. Although testosterone is tough to compound, LGBTQ+ advocates claim that the basic ingredients used to create feminizing hormone medications are widely available at most major drug stores. But sources cautioned that approach: May Márquez, a trans activist based in Florida, stressed that this option “isn’t strictly legal or safe.” But she added that LGBTQ+ people in the state are being forced to practice harm reduction because many feel as if they have nowhere else to turn but to each other.

“I know a friend who literally has vials and vials of bathtub estrogen that they distribute to friends,” Márquez said. “If you’re on trans masculine hormone therapy, a lot of times you’re just basically shit out of luck unless you’re willing to resort to criminal behavior to get some controlled substances.”

Recognizing the rise of DIY medications, groups like Hope & Help, an STI- and HIV-focused clinic in Winter Park, have offered to help trans people self-manage their medication as safely as possible through their syringe exchange program.

For now, Addams fortunately won’t have to take that risk. When we spoke over the phone for the second time, on Aug. 28, he had just gotten his testosterone prescription refilled. The medication was even covered by his insurance. The purchase cost him just $4.15, which was lucky because, he said, he has only $9 in his pocket until his next disability check comes in. His wife usually does the injection for him because he’s afraid of needles, and when he has to do it himself, it takes him at least half an hour to psych himself up. But this time around, he did it on his own in just five minutes, eager to feel like himself again.

The prescription is good for two refills, and Addams hopes that by the time he’s used them up, he will no longer live in Florida. He and his wife have decided that the rollbacks to his health care are simply too dangerous to live with, but it’s hard to figure out where they could land that would be both safe and affordable. The couple have discussed moving to North Carolina to be closer to her father, but things might not be much better there: On Aug. 16, state lawmakers overrode Gov. Roy Cooper’s veto of a trans medical care ban. For now the law applies only to minors, but that could change. Republicans wield a supermajority in both houses of the North Carolina Legislature, meaning they could choose to force through a ban on transition care for adults next session if they elected to do so.

A trans friend of Addams’ recently fled Florida with her family—they’re currently living in an RV in Pennsylvania—but Addams worries that his family couldn’t afford the cost of living in a blue state. While he figures out what’s next, getting his medication refilled is a satisfying victory. “It almost feels like a middle finger to DeSantis,” he said. “Yeah, screw you. We’re going to survive this.”