Trans Mountain's Fusselman Canyon named for Ranger killed in gunbattle with rustlers

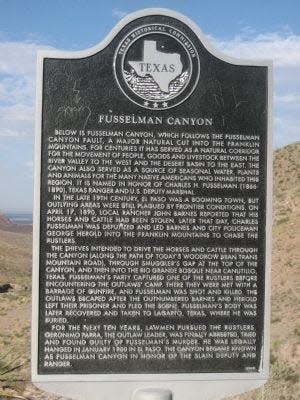

When you drive across Trans Mountain Road you enter through Fusselman Canyon, if you drive from east to west. Fusselman Canyon is named for a Texas Ranger who lost his life there in a gunbattle with rustlers.

Joe Parrish told about the event in an El Paso Times article on Sept. 26, 1965:

Fusselman Canyon

Soon the Trans Mountain Road will conduct an endless stream of cars flashing at 70 miles an hour through Fusselman Canyon, a little-known pass through the Franklin Mountains north of the city.

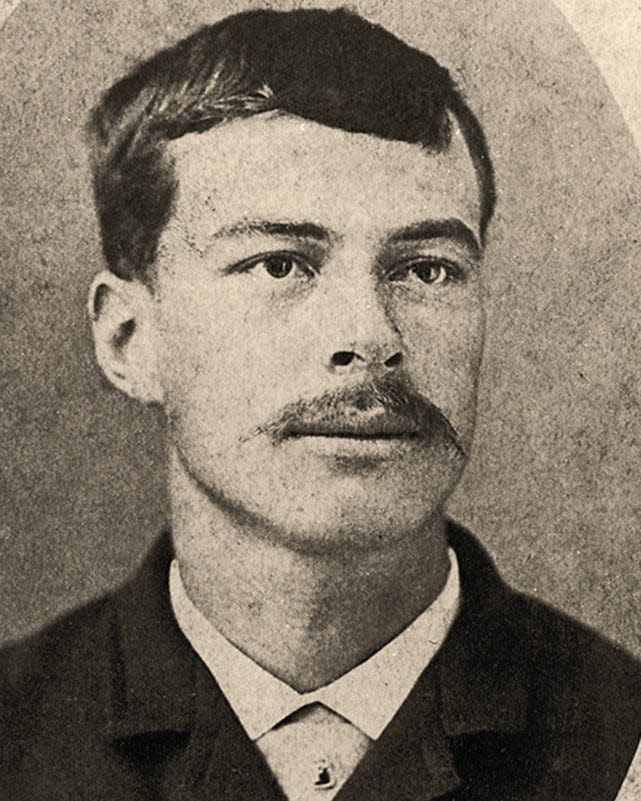

Few persons today know how the colorful canyon got its name. Almost no one remembers the gunbattle with a gang of cattle rustlers in which young Texas Ranger Charles Fusselman met his death in 1890.

Fusselman Canyon slices between the two highest peaks in the range. It is an unspoiled natural park, home of shy deer and sassy porcupine, that should be declared a wilderness area and kept in its primitive state, protected from vandals and litterbugs and name-painters.

On the flank of the north peak there’s a small side canyon which in centuries past was an Indian stronghold. If you know where to look, you can find metate holes in the red rocks where women ground corn. Some of the Indian paintings have survived, hidden in the tumbling rocks. One shows a mounted Indian hunter in the act of spearing a deer. And there’s a small cave, its ceiling blackened by millennia of Indian fires.

More: Pershing Inn bar closes its doors in Central El Paso

Mountain stream

And wonder of wonders … high on the slope there’s a stream of clear cold water that runs almost the year round, a rare thing.

This is the place where Ranger Fusselman gave his life upholding the American concepts of law and justice. A grateful citizenry of that era gave the canyon his name to perpetuate the memory of a brave frontiersman.

Charles Fusselman’s story is the stuff of which frontier history was made. A monument in the canyon to Fusselman would be fitting … a monument to the rugged breed of pioneer lawmen who blazed the path so that we today might live in peace and comfort.

Fusselman’s story began on the morning of April 17, 1890. John Barnes, a rancher with a spread near Mundy Spring, galloped a lathered horse into town.

A gang of thieves

At the Sheriff’s Office, he blurted out his story.

“A gang of thieves rounded up all my horses and some cattle last night," he told Deputy Simmons. “I tracked them to a pass through the mountain about eight miles north of town.”

Also in the office were Ranger Fusselman and El Paso city policeman George Herold, famed for his part in the killing of outlaw Sam Bass at Round Rock, Texas.

Simmons was busy and couldn’t leave, so Fusselman and Herold started out with Barnes on the trail of the rustlers.

Fusselman was known as one of the bravest officers in the Rangers. As sergeant at the Marfa Camp, he patrolled the vast Big Bend country, where just the year before he had engaged in a battle with a gun-crazy outlaw which lasted almost 24 hours. As usual, the Ranger had gotten his man.

The outlaw trail led to the canyon, and it was apparent that the thieves were heading for the badlands of Southern New Mexico, from whence the stolen stock could be driven north to more settled areas, south into Mexico, or on out into Arizona. The three spurred their horses; Fusselman wanted to catch them before they left Texas and his jurisdiction.

Jumped an outlaw

They entered the canyon and almost immediately jumped one of the outlaws, a rear guard, Ysidoro Pasos.

Pasos, taken by surprise and with three gleaming pistols aimed ominously at his belly, surrendered without a fight.

Taking Pasos in tow, they continued following the trail. Fusselman was in the lead, followed closely by Herold. Barnes was some distance behind, guarding the prisoner.

Now, it was the officers’ turn to be taken by surprise. They topped a ridge and found themselves almost on top of the rustlers’ camp, only yards away.

The outlaws immediately fired. The first shot missed. Not waiting to unsling his rifle, Fusselman drew his pistol and yelled, “Boys, we’re in it and let’s stay with it,”

The Ranger grabbed his forehead

Then Herold saw one of the outlaws, Geronimo Parra, leader of the gang, aim a rifle at Fusselman and pull the trigger. The Ranger grabbed his forehead and fell backward out of the saddle, fatally wounded.

There were eight or 10 of the rustlers, and now they charged the lawmen, laying down a murderous fire as they advanced up the hill. Herold and Barnes were badly outnumbered. So, they released their prisoner, wheeled their mounts and beat a hasty retreat.

Knowing the lawmen would spread the alarm, the rustlers beat a retreat of their own. Abandoning the stolen stock, they mounted and fled. The stony canyon walls rang with hoofbeats as the gang galloped through the pass and out the west side of the mountain. They pushed their horses down through the sandy foothills, threaded their way on a secret path through the treacherous bosque near Canutillo, and split up.

More: Old Glory Memorial, which honors those who have served, turns 20: Trish Long

Gives alarm

Herold arrived back at El Paso at 5 p.m. and gave the alarm. Fusselman had been very popular, and feelings against the outlaws ran high. Deputy Marshal Bob Ross organized a posse of 10 heavily armed men and took up the chase. A wagon followed the posse to bring in Fusselman’s body.

The wagon returned at 1 p.m. the following day bearing the lifeless form of the slain Ranger. As it passed down San Antonio Steet, passersby became silent, respectfully doffing their wide-brimmed hats. The sorrowful cortege turned into the Star Stable where, according to the peeling wooden sign, “Fine Livery and Undertaking” were available, together with “Blacksmithing, Woodwork and Carriage Painting. Wagons, Buggies, Etc., Bought and Sold. M.A. Dolan, Prop”

A crowd surrounded Frank Gaskey, driver of the wagon, clamoring for information. Gaskey obliged by relaying what he had seen.

“We reached the canyon,” he said, “about eight o’clock last night. It was too dark to follow the trail, and besides, the gang might have ambushed us. So, we pitched camp and waited until this morning. At daybreak Herold led us up the canyon and up on a ridge where we found Fusselman’s body.”

18 horses, two cows and a calf

Just then Tivoloro Riverall and Officer Juan Franco came down the street driving 18 horses, two cows and a calf which had been abandoned in the canyon by the fleeing thieves.

The crowd pressed the newcomers for further details. Franco said that one of the bandits probably had been wounded, because a trail of blood could be followed some distance from where Fusselman’s body had been found.

The posse had bad luck. It couldn’t find a way through the bosque. Constable Patterson had ridden his horse into the bog a few feet and it sank to its belly in mud. Then, too, the overnight head start by the outlaws made pursuit useless. So, the posse returned to town.

More: Pat Garrett's gun skills the talk of Coney Island: Trish Long

Chase by Ranger also was useless

The Sheriff’s Office had notified the Ranger camp at Marfa of Fusselman’s death. Ranger Capt. Frank Jones dispatched Cpl. John R. Hughes to El Paso to see what he could do about catching Fusselman’s murderers.

But he, too, was forced to abandon the chase as useless. Then he was ordered back to Marfa for another assignment. In 1893 he was promoted to captain to succeed Jones, who had been killed in a gunbattle with the notorious Olguin Gang on The Island near San Elizario. Hughes was placed in command of Company D, stationed at Ysleta. He never relinquished his goal of capturing Charles Fusselman’s killer.

A few years later he located Parra but couldn’t do anything about it. His man was serving a stretch in the New Mexico State Penitentiary.

But when Parra was released in 1899, Hughes was camped on the jailhouse steps. He arrested Parra, brought him to El Paso and charged him with Fusselman’s murder. Parra was found guilty and sentenced to hang.

The hanging took place in the old City Jail on South Campbell street, which was razed a few years ago The jail contained a fancy steel gallows that had been built right into the building, and worked right up to the day the wrecking crew set to work.

Trish Long may be reached at tlong@elpasotimes.com or 915-546-6179.

This article originally appeared on El Paso Times: Trans Mountain's Fusselman Canyon named for Ranger killed in gunbattle