A transgender student, her crusading mom — and an English teacher caught in the middle

This article is adapted from “Grapevine,” a six-part NBC News podcast about faith and power — and what it means to protect children — in an American suburb.

GRAPEVINE, Texas — High school teacher Em Ramser felt her stomach drop when she noticed an empty seat in her second-period English class one morning in January 2021.

“You know you get that sudden feeling,” she said, “where you know something is really wrong?”

The missing 14-year-old student reminded Ramser of herself when she was that age — unhappy to be at school most days and wrestling with her identity.

At the start of the school year, Ramser had asked every student to fill out a form answering questions about themselves, including how they wanted to be addressed. The absent student, listed as a boy in district records, had asked to be called by female pronouns, and by an alternative name: Ren.

Ramser, 25 at the time, was in her first year at Grapevine High School, in the conservative, sprawling suburbs northwest of Dallas. She had set out to make her classroom the safe space for LGBTQ teens that she wished she’d had while growing up queer in North Carolina. So, she said, she was happy to accommodate Ren’s request.

But Ramser had no idea what was going on between Ren and her mother — or that the three of them would soon become entangled in an emerging nationwide clash over religion, politics and transgender acceptance in public education.

After her class that day in January 2021, Ramser went down to the school’s office to ask if anyone had heard from Ren or her mother.

A call home confirmed Ramser’s gut feeling: Ren was missing.

Three hundred miles away, Ren sat on a Greyhound bus as it rumbled down a West Texas highway, through a vast expanse of ranchland dotted with windmills and oil wells.

After getting dropped off at Grapevine High that morning, Ren had caught a ride to a bus station, where she’d purchased a one-way ticket to Denver — as far northwest as $150 could take her.

Ren didn’t have a plan for what she would do once she got there. All she knew for certain, she said, was that she was going to get away from Grapevine — and away from her mother, Sharla.

It had been more than a year since Ren finally built up the courage to tell her mom she was transgender. For years, the two had attended weekend services at evangelical churches where pastors taught that homosexuality is a sin, and that it’s immoral for people to identify as a gender that does not match the one assigned at birth.

Afraid of how Sharla would react, Ren says she had at first tried easing into the conversation, asking, “Hey, what do you think about trans people?”

Once Ren made clear why she was asking, she said her mom brought up religion and told her that “God made me the way I was meant to be.”

Sharla declined interview requests, but she has shared her views about her child’s gender in private messages to Ren’s father, on a personal blog, in social media posts and during public remarks at a school board meeting last year. (Ren now goes by a different name, but to protect her privacy, NBC News is not publishing it or her family’s last names.)

Ren was coming of age in the midst of a stark generational shift in America. In an era of rapidly expanding acceptance, the number of young people identifying as trans had nearly doubled from a few years earlier. But a new backlash movement had been brewing, fueled by an emerging — and largely unsupported — belief among some parents that social media and peer pressure were causing teens to change genders.

After Ren came out in 2019, Sharla emailed her ex-husband, Rich, who lives in Oregon, to let him know she was worried. “I have assured him I will love him no matter what,” Sharla wrote, using a male pronoun to refer to Ren, “and we will get through this together.”

Rich, who provided copies of his correspondence with his ex-wife, told Sharla the best thing they could do was to embrace Ren for who she was.

But to Sharla, helping Ren “get through this” meant seeking help to overcome what she’d begun calling her child’s “gender confusion.” Sharla took Ren to see a Christian counselor who, according to his website, promised to help patients become “the person they were created to be.”

Ren says she learned to hide her identity while at her mother’s home. Only when she was with her father in Oregon and at her school in Grapevine did she feel somewhat free to present herself as female. That was especially true in freshman-year English.

Ramser didn’t know it, because Ren was so quiet, but her class meant a lot to her.

“She just took extra care in getting to know you and making sure that you were comfortable,” Ren said. “She just made you feel safe.”

But even with that support, Ren said it wasn’t easy living two lives. She was feeling suffocated at home and was losing motivation to keep up the facade. “I felt like I had to do something,” Ren said. “I wanted to do something. And then I did.”

She got on the bus that day in January 2021, heading northwest amid a rush of conflicting emotions: “Scared, excited, sad, happy.”

And then, disappointment.

During a stop in Lubbock, Texas, an officer came aboard and pulled Ren off the Greyhound. She was led into a government office, where she waited to be picked up by her mother.

Ren was quiet as she and her mom got on the road and began the five-hour drive back to Grapevine.

Em Ramser hadn’t set out to become a teacher. She discovered her love for the profession in college, while studying to become a writer. To help cover her bills, she’d taken a job teaching creative writing to teens, and at the end of the summer program, one of her students wrote a heartfelt letter that she’s held on to ever since.

The girl, who’d recently come out as gay, said Ramser was the first openly queer role model she’d ever had, which had given the student hope for her future.

When she was a teen, Ramser didn’t have a trusted adult at school who she could go to after a classmate shoved her to the ground and called her an anti-gay slur. At Grapevine High, she strived to be that adult.

Ramser also cherished her role teaching English as part of the district’s Aspire Academy, an accelerated program for academically gifted students.

Late on the evening of Ren’s disappearance, Ramser felt a weight lift off her when she got a message from another student: The teen was safe.

That week, Sharla emailed Ramser to let her know her child would not be attending school in person for a while.

Given the runaway attempt, that made sense to Ramser. She still didn’t know about Ren’s homelife. They’d rarely discussed anything in class beyond reading assignments or video games.

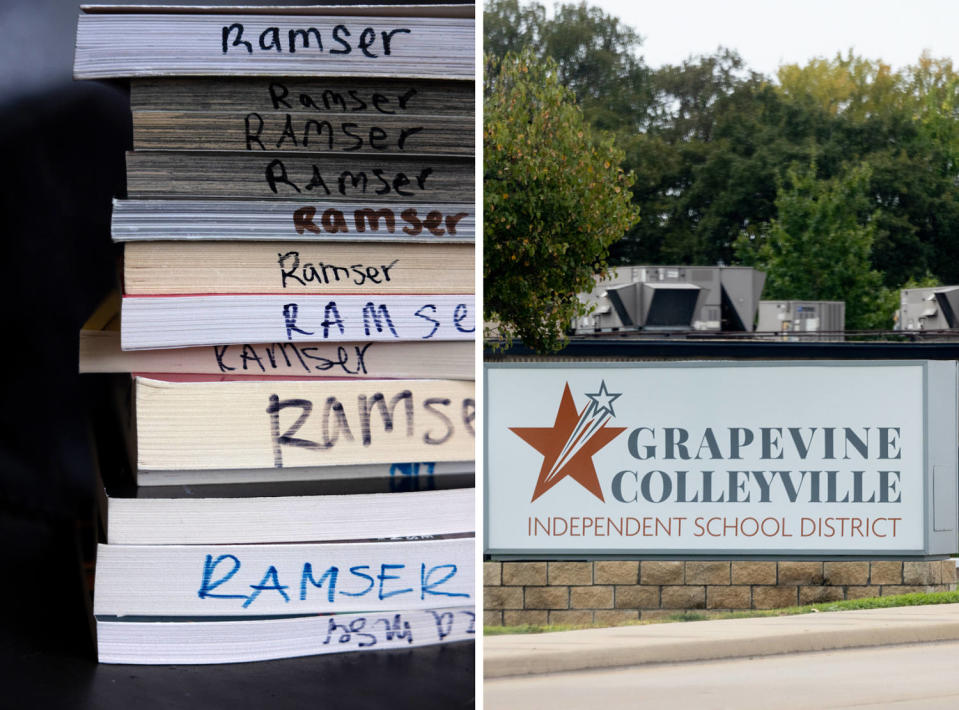

But a few days later, Ramser got a call from her principal, Alex Fingers. Sharla had emailed Fingers to complain about a book she’d found in Ren’s room. It was called “The Prince and the Dressmaker,” and it had Ramser’s name written on the side.

The graphic novel by Jen Wang tells the story of a prince who loves to wear dresses but, fearing rejection from his parents, keeps his fashion hobby hidden. When his secret is finally revealed, the prince runs away from home, only to return in the end and discover that his mother and father still love him, no matter what he wears. (Universal, which is owned by the same parent company as NBC News, purchased the film rights in 2018.)

It was one of hundreds of titles that Ramser kept in her classroom library, a collection of books that students borrowed and read in their free time. Earlier that school year, Ren had checked out “The Prince and the Dressmaker” after a classmate recommended it.

Now Sharla was alleging in her email that Ramser had made Ren read the book, and that its coming-of-age storyline had helped inspire her child to run away.

“I was like, ‘No, I didn’t make Ren read it,’” Ramser said. “And also, if you notice at the end of the book, it says you should never run away. The book portrays it as being that your family will always love and support you.”

Ren confirmed Ramser’s account and denied that the book had inspired her to buy the bus ticket. After looking into the matter, Fingers determined that the English teacher had done nothing wrong, according to messages Ramser shared.

At the time, in early 2021, parents had not yet started flooding public schools with demands to ban library books dealing with sexuality and gender, and Sharla’s complaint didn’t seem like a big deal to Ramser.

Ren finished the school year attending classes over a video feed, a pandemic-era accommodation for families not ready to return to in-person schooling.

On one of the final days of school before summer break, Ramser discovered her copy of “The Prince and the Dressmaker” lying facedown outside her classroom door.

She picked it up and flipped through its well-worn pages.

Ren’s mom must have finished reading, Ramser thought at the time. Maybe Sharla had decided the book was fine.

One year after Ren’s runaway attempt, in January 2022, Sharla found girl’s clothing in Ren’s bedroom, setting off a new round of arguments.

Afterward, Sharla texted her ex-husband. Their child, she said, was in desperate need of psychiatric care “to help with gender dysphoria.”

Rich had been taking a much different approach to Ren’s gender identity. After she came out to him on a long car ride, he remembered telling her, “Is that it? Is that what you were so worried about telling me?” Rich said he told Ren what mattered to him was that she worked hard and was kind.

In his mid-60s and having grown up in a vastly different era, Rich said he did his best to understand and accommodate his child — sometimes messing up along the way. He struggled at first to use the right gender titles around the house. So he and Ren’s stepmother made a pronoun jar and dropped in a dollar every time one of them said “he” instead of “she.”

To Rich, Sharla’s latest plans for treating Ren sounded like conversion therapy, a practice that’s been shown to increase the risk of suicide among LGBTQ teens. Rich responded with a link to American Psychological Association guidelines that said providers should affirm teens’ identities.

Sharla fired back with a text saying LGBTQ people “have corrupted Biblical morality and thinking.”

“You are his father and should be guiding him in moral ways,” Sharla wrote, “not accepting whatever sexuality he wants to assign himself.”

The messages frightened Rich, who felt that Sharla was becoming “more militant” in her views. This came at a time when Republican officials in Texas and nationwide were starting to crack down on what some conservatives had begun calling “woke gender ideology.”

That February, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott directed the state’s child welfare agency to begin investigating parents who sought gender-affirming medical care for their children. Abbott’s letter classified care like hormone therapy and puberty blockers as child abuse and called on professionals and members of the public to report families they suspected of seeking such treatments.

For Ren, 15 at the time, Abbott’s directive felt like a breaking point. A day later, she typed out a note on her phone.

“Living my life as a boy has taken a noticeable toll on my mental health recently,” she wrote. “I have reached a point in which I can no longer take this.”

A year after trying to escape by bus, Ren had devised another way out of Grapevine.

“In the summer following this school year,” she wrote, “I will be attempting to go to court to transfer primary custody to my Father.”

After composing the note, Ren thought about posting it somewhere or sending it to her friends. In the end, she sent it only to one person: her dad.

The two had long talked about the possibility of Ren coming to live with him in Oregon after high school. The note helped Rich to more fully understand the depths of his child’s despair and made him realize Ren couldn’t wait another two years to move.

Once she turned 16 that spring, Ren would have the legal power to petition a court in Oregon for a change in custody. Rich hired two attorneys: one to represent him, and one to represent Ren.

They told Sharla nothing of their plans. When Ren arrived in Oregon for summer vacation at the end of the 2022 school year, Rich filed paperwork petitioning the court for full custody. In messages to Rich and Ren, Sharla promised to fight.

But after the Oregon judge overseeing the case directed Sharla and her lawyer to refer to Ren only by her chosen name and female pronouns during court proceedings, it seemed clear to Rich that the court was likely to side with the parent already affirming Ren’s gender identity.

Rich said the lawyers drafted an agreement that would grant him sole legal custody. Under the terms, Sharla would be allowed to have contact with Ren only if the teen agreed to it.

In a social media post later, Sharla complained about being forced to call her child “she/her” and said she was “devastated.”

Before signing away custody, she traveled to Oregon in June 2022 to see her child in person. Ren said the brief meeting in her bedroom was awkward. Her mother, she said, repeated “all the things that she’d been telling me for years” about God and biology.

In what might have been her final encounter with her only child — whom she’d long called her “miracle” — Sharla said she’d issued a warning.

“I told him he has made a tough decision, and he will have to pay the consequences,” she wrote on social media. “When he finds out the truth, he is always welcome home.”

On Aug. 22, 2022 — three weeks after Sharla officially gave up custody of Ren — the Grapevine-Colleyville Independent School District board of trustees convened a special meeting.

That spring, conservative candidates backed by a far-right Christian wireless provider called Patriot Mobile had secured a majority on Grapevine’s school board, and now they were preparing to enact their vision for the suburban school district.

The school board’s 36-page proposal banned lessons on systemic racism. It gave school employees the right to refer to trans and nonbinary students by pronouns and names matching the ones they were assigned at birth — practices known as misgendering and deadnaming — even if a student’s parents supported their child’s gender expression. And the policy prohibited reading materials or classroom discussions mentioning the possibility that someone’s gender could be different from their biological sex.

Em Ramser and several other Grapevine teachers were worried that the policies would make it harder to teach their students about the history of racism in America and affirm the identities of LGBTQ teens.

Nearly 200 people signed up to speak during public comments, to either thank the board for protecting children from dangerous ideas about race and gender — or to tell them that they were in fact hurting students.

After four hours, a distraught mom with short blond hair and wire-framed glasses stepped up to the microphone. Sharla had come to speak in support of the new policies and to share a warning for other parents.

“The doctrine of gender fluidity brings disorder, chaos, anarchy and confusion into our schools and classrooms,” she said. “A younger teaching generation is pushing and has been pushing that our kids can be any gender they want to be. This is biologically incorrect.”

Sharla told the board she’d watched it happen to her child.

“Certain staff were labeling him, feeding him incorrect information, especially about his ‘unaccepting mom,’” she said. “Instead of the adult influences bringing my son’s issues to me, the parent, they told him I rejected him because he wanted to be female. This was so far from the truth.”

As a beeper sounded, signaling that her one minute was up, Sharla told the board, “I lost my son.”

That night, the school board voted 4-3 to approve the new policy.

Sharla saw it as a victory — an affirmation that her fight was justified. Soon, she would find a bigger audience for her accusations. And this time, she would name names.

Four days later, Em Ramser was greeting students in the hallway when another teacher approached and asked, “Are you OK?”

Ramser didn’t know what she was talking about. Then the colleague handed Ramser her phone, showing an article headlined, “Bombshell Claims of GCISD Teacher Misconduct.”

After scrolling, Ramser realized the story was about her, and she started to cry.

Sharla had spoken to the Dallas Express, a conservative news site published by a local hotel magnate. The article quoted Sharla and an email she’d written to Fingers, Grapevine’s principal, that summer, amid her custody dispute.

In the email, Sharla told Fingers that Ramser had “infected” her child with a dangerous ideology and encouraged Ren to change genders. Sharla also alleged that Ramser had a personal library of LGBTQ books, including “The Prince and the Dressmaker,” that she passed around to indoctrinate students.

The article linked to Ramser’s social media and personal website and noted that she identified as queer.

Ramser was shaking as she read.

“It felt like being plunged into an ice bath,” she said, “and you can’t catch your breath.”

Someone offered to watch Ramser’s class, and she headed to Fingers’ office. He told her to make lesson plans and to head home.

For days afterward, a substitute ran her classes. All year, she’d seen news coverage of right-wing militias like the Proud Boys protesting with AR-15s outside of family friendly drag performances, including in Dallas. She was worried that someone like that might show up at her house, or at school.

Parents were sharing the article on community Facebook pages, where some users left comments suggesting Ramser should be arrested or fired.

“This woman has no business being near children,” one parent wrote.

“Time to take out the trash,” wrote another.

It didn’t help, Ramser said, that the school district had issued a statement in response to Sharla’s allegations that failed to note it had already investigated and found the teacher had done nothing wrong.

As Ramser’s email filled up with threatening messages accusing her of sexually “grooming” children, she said she couldn’t bring herself to get out of bed. One person wrote to say they hoped Ramser got monkeypox and died. Someone else spammed her inbox with links to porn sites. Her mother noticed the toll the harassment was taking, at one point bluntly telling her daughter, “If you kill yourself, I’m going to sue that school district.”

A few days after the article was published, Ramser asked Fingers and other school leaders to put out a new statement defending her. The principal told Ramser he supported the idea, but the decision would rest with senior administrators who answered directly to the school board.

In the meantime, Fingers advised Ramser to remove rainbow pride stickers from the nameplate outside her classroom and any other decorations that might signal anything about her identity or personal beliefs. Fingers, who’s Black, made the recommendation during a phone call, which Ramser recorded.

“I don’t have a Black Lives Matter poster,” Fingers told Ramser. “I don’t have a GSA flag. I don’t have anything. … I’m not giving any extra ammunition, because I love all kids.”

Ramser reluctantly removed the rainbow stickers, but the district never put out a new statement.

Fingers didn’t respond to interview requests. In response to written questions about Ramser’s case, a Grapevine-Colleyville spokesperson said the district does not share findings of personnel investigations and “has always remained committed to serving and supporting all students, families and staff, and ensuring that they feel safe and welcome.”

Ramser thought about quitting, but she ultimately decided to return to class the following week. She worried about the message resigning midschool year might send to students.

“I didn’t want to show them that when things are hard, you hide.”

Two thousand miles away, Ren was still getting used to life away from Grapevine, and away from her mother. She wore dresses to class at her new school in Oregon, and she felt no pressure to keep those clothes hidden when she was at home.

Under her father’s supervision, and following months of evaluations by doctors, she’d started receiving puberty blockers and estrogen to aid in her physical transition.

She was also watching with growing concern as her mother took their private dispute public.

“I hate it, but what am I going to do about it?” Ren said. “I can feel bad about it, that’s pretty much it. That’s what I’ve been doing.”

Ren denied the story Sharla told. Ramser hadn’t encouraged her to change genders. Ren hadn’t gotten the idea to run away from a graphic novel. Nobody at Grapevine High School had told her to reject her mother.

“It wasn’t Ms. Ramser’s fault that any of that happened,” Ren said. “She was a good, supportive figure in my life. She was a good thing that happened to me.”

Rich, meanwhile, was furious when he saw Sharla’s comments to the school board and Dallas Express. Afterward, he wrote to Fingers, defending Ramser.

“It’s turned the truth upside down,” Rich said of Sharla’s allegations. “The story she told is absolutely the truth upside down.”

Nevertheless, Sharla continued her campaign that fall.

She created a Facebook page titled, “Woke Mama Bear: Gender Truth God’s Way,” and filled the feed with Bible verses and photos of her newly estranged child, back before Ren openly identified as a girl.

She also launched a YouTube channel and recorded a video alerting parents to the toxic ideology that she believed was poisoning children’s minds and destroying families.

“If we don’t fight this now, we’ll have a whole generation of lost children who make decisions they regret,” Sharla says over a haunting piano track. “Fight woke, while you still can.”

Later, on her personal blog, Sharla wrote of relying on her faith to get her through.

“Any loss of parent/child, friend or spouse relationships,” she wrote, “is unmatched to the gain of knowing Christ.”

Ramser’s classroom was transformed in the months after Sharla’s allegations.

She boxed up her entire class library — a collection of donated and purchased books she’d accumulated over the years — and brought it home. She took down the artwork that had been given to her by members of the LGBTQ student club, and the district printed a new nameplate to replace the one covered by rainbow stickers.

“It’s been consistently stripping every bit of personality away,” Ramser said.

As the school year dragged on, she no longer recognized the teacher she’d become, and it was getting harder to see a future for herself in the Texas public school system.

She decided to leave at the end of the academic year.

“For once,” she said, “I had to put myself above the kids and say, ‘I can’t do this anymore.’”

But before she left, there was something Ramser felt she needed to do.

In May, with only days left at the district, Ramser signed up to speak at a school board meeting.

She’d spent weeks rehearsing what she would say during the one minute allotted to her. After the clerk called her name, she strode to the same lectern where Sharla stood nine months earlier.

She opened by telling the board that teaching at Grapevine’s Aspire Academy had been her dream job.

“And yet, at 27, I am leaving as this community has continuously harassed me,” Ramser said. “To the point that there were days I didn’t even want to be alive anymore, much less be a teacher.”

The message could not have been clearer, Ramser told the board: “Y’all don’t want people like me, people who might be gay, to teach here.”

To close, Ramser had a message for her students, past and present — including the one whose mother’s allegations were helping drive her out of Grapevine.

“I want you to know that you did nothing wrong. And I am so incredibly proud of each and every one of you.”

“I wish,” Ramser said in a shaky voice as her time expired, “that I could have been the teacher that this district wanted.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com