What Translating a Firsthand Account of Life in Auschwitz Taught Me About the Language of Suffering

Seventy-five years ago, on a cold winter’s day — Jan. 27, 1945 — the Dutch Jewish doctor and trainee psychiatrist Eddy de Wind saw Russian troops in white camouflage suits stroll up the road “as if no Germans existed” and enter Auschwitz concentration camp. Soon after, he and other newly liberated prisoners were taking turns to dance on a large portrait of Hitler they had dragged out of an office. “I don’t remember what I felt,” De Wind wrote later. “Rather than a fine way of venting my hatred, I probably found it ridiculous… I don’t think any of us were capable of experiencing real emotions at that stage, not sorrow, not hate, not longing.”

He’d spent more than 16 months in the camp with his wife, Friedel, who had been forced out of Auschwitz at gunpoint a week earlier during the murderous evacuations that would come to be known as the Death Marches. De Wind did his best to cling to hope, but everything he saw and heard made her survival seem less likely and he had no news of her until he finally made it back to the Netherlands on July 24, 1945, “the day of the miracle,” when a Red Cross worker told him that “a Mrs. de Wind from Auschwitz” was in a nearby hospital.

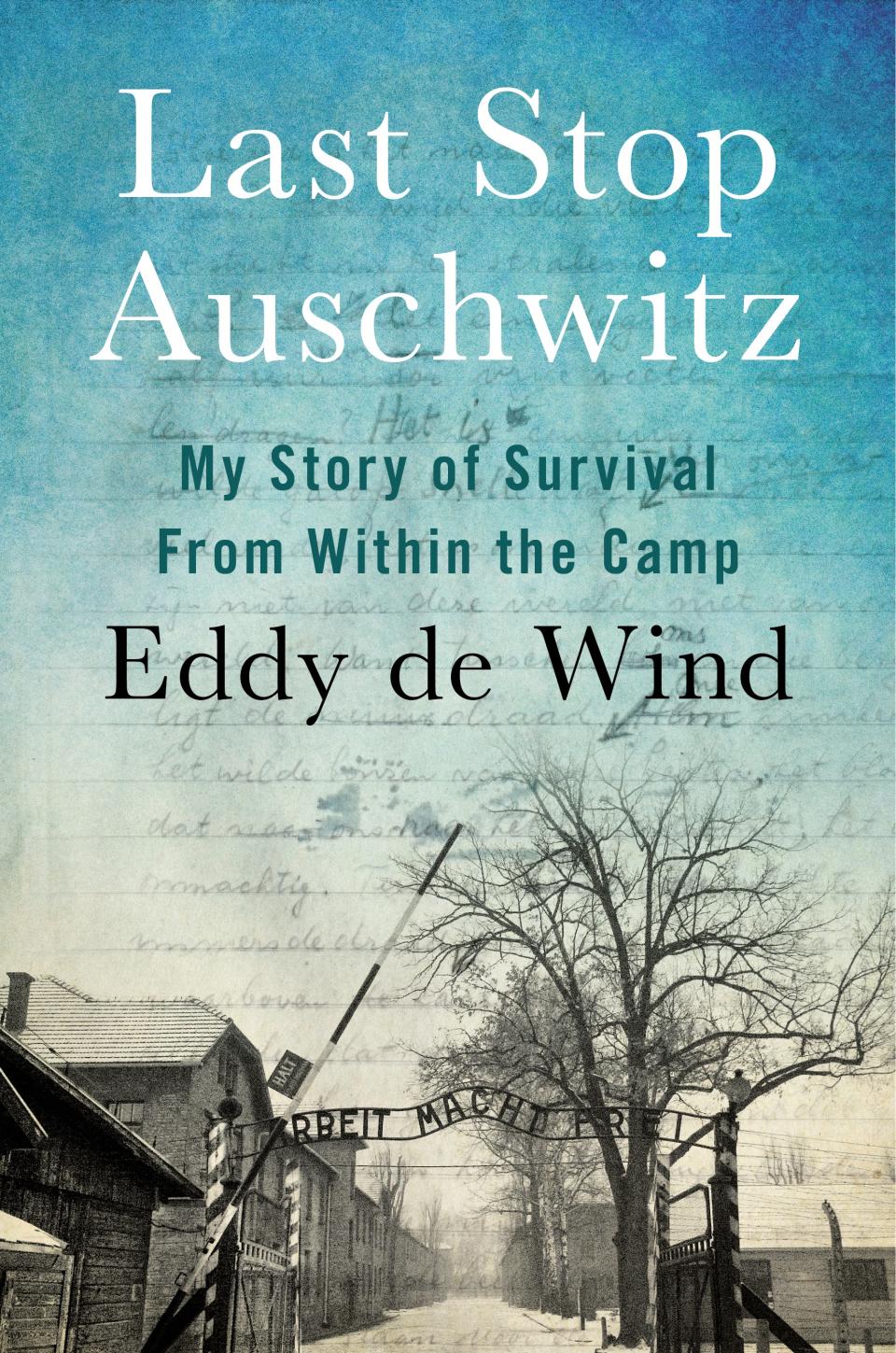

Before being reunited with Friedel, De Wind had stayed in Auschwitz for another three months at the request of the Russian medical detachment, helping to treat the survivors by “performing all kinds of difficult medical procedures, carrying out amputations and small operations that were essentially far beyond [his] capabilities.” It was in this period that he wrote Last Stop Auschwitz—in the evenings, sitting on his bunk in a former Polish barrack, after long days working in the hospital—driven by the one emotion he was sure of, his pressing need to let other people know what he had seen and suffered. “If I record it now,” he wrote, “and everyone finds out about it, it will never be able to happen again.”

De Wind’s account of his experiences in Auschwitz, taken more or less directly from his notebook and first published in the Netherlands in 1946, occupies a middle ground between memoir and historical document: written after the fact, but on location and soon after the events it describes, sometimes just weeks later. Trying to identify what exactly makes the book so compelling, novelist Heather Morris wrote, “In all other accounts and testimonies given many years after the suffering, there was at times a disconnect between memory and history… In Last Stop Auschwitz, written when it was, there is no separation of these two, the waltz perfectly in step.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

In 1980, when seeking republication, De Wind turned down an offer from a leading Dutch publisher who saw a rewrite as a prerequisite, choosing instead a smaller house that aimed for as faithful a reproduction of the original as possible. De Wind knew this approach could expose him to “criticism for the style and immature political statements” but preferred “the greater guarantee of authenticity.”

Forty years later, as his English translator, I bore this in mind and did my best to translate the book De Wind wrote rather than the polished version he rejected. The rawness and immediacy go hand in hand with the authenticity he demanded. Some of his transitions are abrupt, the pacing can be uneven, there may be some repetition and confusion as figures appear and disappear in the narrative, but none of this matters. What matters is his personal account of the Nazis’ crimes and the ordeal of the men and women who survived or, much more often, perished; his surprisingly early insights into the psychological and political processes at work; and the urgency with which he describes the killing machine he was caught up in. I wanted it to be good English, of course, but English that felt as much like the Dutch as possible.

An important exception was the spelling of names, which De Wind often approximated or wrote down phonetically, presumably because he had only heard them and had never seen them written down. It’s hardly surprising that a small publisher in war-ravaged Amsterdam had few resources for fact checking and, in the immediate post-war period, when the Nuremberg trials had only just begun and knowledge of the camps was still relatively limited, it would have been extremely difficult to obtain information that is now just a few clicks away. It was only natural, then, to correct “Glauberg” to “Clauberg,” “Klausen” to “Clausen,” and “Döring” to “Dering.” A benefit of the book coming out more or less simultaneously in some twenty languages around the world was being able to consult with the German, Polish, Hungarian and other translators in a lively Google group.

Translation is never easy and with such an important subject getting it right is even more important. When De Wind described kapos and soldiers armed with stokken, for instance, the Dutch word could mean many things: “sticks,” “canes,” “branches” or “bars.” By chance, I happened to go to Poland while translating the book and was able to visit Auschwitz, where I saw drawings and photos of German soldiers brandishing both walking sticks and cudgels made from sturdy branches. In another room I saw prisoners’ uniforms in a display case and took photos of the wooden shoes and sandals mentioned in the book, glad to clarify the distinction between them. In both instances I ended up using the most literal translation, but that too is part of a translator’s task: putting in time and effort to make sure that the most obvious choice is actually correct. Proof once again of Dutch poet Adriaan Morriën’s old adage that a translator is someone who looks up words they already know in the dictionary.

David Colmer translated the new English edition of Last Stop Auschwitz: My Story of Survival From Within the Camp by Eddy de Wind, available now from Grand Central Publishing.