Transparency, open meetings and FOIA critical to good governance — and citizenship

What are the rules to good governance?

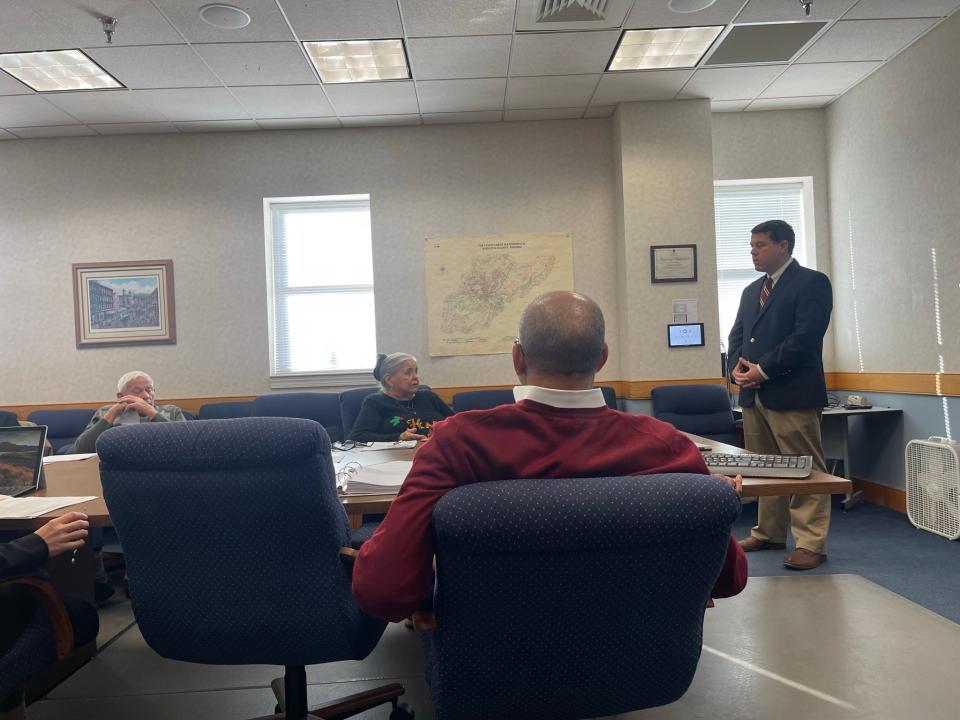

This question is central to a presentation given to the new, and some previous, members of the Staunton Economic Development Authority (EDA) on Thursday, Nov. 30. The addition of Boardmember Betty Jordan led to the first new boardmember training since 2021.

The training covered a variety of topics, including a review of Staunton Crossing, but City Attorney John Blair’s focus was on keeping the EDA open and transparent for anyone interested in following the city’s business.

Starting with the basics, what is a meeting? Blair explained the “rule of three,” defining a meeting as whenever more than two members of a board gather and discuss the board’s business. Because of this, Blair cautioned members to be conscious of where and with whom they discuss board business.

See three members of the same board in public? The rule of three means they can't talk business

“Here is my advice to you,” Blair said. “[Let’s say] three of you randomly meet on the street. You might have all been at the Christmas parade. You might all attend the same church, whatever it is. … If you’re not talking about EDA business, it’s not a meeting. If more than two of you see each other out at any gathering, don’t talk about EDA business. As long as you follow that rule, you’re not going to violate the Freedom of Information Act.”

The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) is a federal law requiring public meetings be open to the public and mandating that the place, time, and date of the meeting be freely available three working days before the meeting begins. In Staunton, meetings times and agendas are posted online and on a bulletin board in city hall. Although not part of this process, the News Leader publishes The Agenda online on Tuesday, containing a list of notified meetings for the week running from Tuesday to Tuesday.

The meeting notice is out, but what's on it, and can that change?

Although a meeting must be noticed properly, the agenda is different. Virginia law (§ 2.2-3707) states “at least one copy of the proposed agenda and all agenda packets and, unless exempt, all materials furnished to members of a public body for a meeting shall be made available for public inspection.” If there is a draft agenda, it should be provided, but the agenda can be changed by the board during the meeting.

The phrasing in the law accounts both for the draft agenda, which is a list of what the board expects to talk about during the meeting, and the agenda packet, which is usually a much larger document including whatever documentation is relevant to the agenda items, such as a certificate of appropriateness application for the Historic Preservation Commission or a request for a special use permit to the Augusta County Board of Zoning Appeals.

What opens a closed session?

When can more than two board members discuss things in private? In a closed session, which is only available to discuss specific items as allowed by the law (§ 2.2-3711). Examples include personnel discussions, such as a performance review, and real estate transactions, as long as the transaction is not taking place during the closed session. Blair explained this is because “the moment that the public knows about a particular real estate transaction and the details, what do you think happens when you want to sell the property or buy the property? Prices will go haywire.”

Taking notes or recording sessions is legal, no matter what anyone tells you

These rules led to a question from Betty Jordan – “I was just curious about taping a [closed] meeting or taking notes? I don’t plan on doing it, but it’s been something that's been a buzz over there. To me, it shouldn’t be, it’s not ethical.”

The question addresses an ongoing battle between the Augusta County Board of Supervisors and one of its own members, Scott Seaton. Seaton recorded a conversation the board had while in closed session. When asked by the board to turn the recording over, Seaton refused. After refusing to give the board all of his copies of the recording, the board censured Seaton, removing him from all boards and commissions, but later noted he had not broken the law.

What are the rules for recording meetings? Virginia law specifies “any person may photograph, film, record, or otherwise reproduce any portion of a meeting required to be open” (§ 2.2-3707). In addition, Virginia is a one-party consent state for audio recordings (§ 19.2-62), meaning that one party in a conversation can legally record any conversation, public or private, without getting the permission of others in the conversation.

Blair emphasized that he did not know the details of the Board of Supervisors battle, and he could not speak to them directly, but gave an answer specific to how EDA board members should think about Jordan’s question in the context of their positions.

Public service should not come with certain benefits

“As EDA members [here are] a couple of things to keep in mind. If I’m giving you legal advice … then you were to go out and tell a third party, the attorney/client privilege is potentially broken. … There is a prohibition in the Conflict of Interest Act that says you cannot use confidential information to help yourself or your friends. … Let’s say someone said ‘the Freedom of Information Act doesn’t prohibit me from telling x about the EDA wanting to acquire this property.’ The Conflict of Interest Act does. You can’t use this for your own personal benefit.”

The Conflict of Interest Act, a Virginia law, specifies that public board members cannot take gifts from lobbyists, companies that have hired lobbyists, or anyone that’s trying to get a contract with the board. However, Blair emphasized that this does not prohibit EDA members from receiving gifts completely.

“‘I got a gift from my spouse, or my adult son or daughter took me out to eat, do I have to report it?’ Are they a lobbyist? … If not, you don’t need to worry about it,” Blair explained. “99.99 percent of gifts you don’t have to worry about.”

EDA Chair Alison Denbigh provided a real-world example, saying “I do a lot of meetings and dinners with people in economic development and other businesses up and down the Shenandoah Valley. I try not to ever let them pay because I don’t know if they have a motive that I don’t know now but could be later.”

Explaining personal interest and recusal

Another situation that can emerge is when a board member has to consider board business that relates to their personal business or finances. The best practice is for the board member to recuse themselves from voting on the item.

“Let’s say the EDA needed to buy land and, lo and behold, the land they needed to buy was your land and where you live,” Blair said. “They need to buy your home. Do you think you should vote on that? We sometimes over-complicate these things, but the law says you cannot have an interest in any transaction that comes before the EDA. Personal interest is defined as $5,000 or greater interest in a property, business, stockholding, … those are the main ones.”

Blair noted that a ‘typical’ call he receives is a representative asking if they can vote on business relating to a property in their neighborhood that is not their home.

The engine that powers good investigative journalism — and your right to know: FOIA powers

Another important aspect to the Freedom of Information Act is the FOIA request, where a member of the public can request documents related to a public official’s work. This can include draft minutes after a meeting ends, emails and texts to and from board members about board business, financial records, and much more.

“Every document in your possession, including emails and text messages that discuss EDA business is public record,” Blair told EDA members. “Individuals, and the news media, can submit what’s called a Freedom of Information Act request. They might say ‘I’d like to see all your emails from the past month discussing EDA business.’ What you would do is contact the city attorney’s office. The city’s Freedom of information Act officer is Robin Wallace. … We will then guide you through that process. Any email that relates to EDA business, keep it for five years.”

Following FOIA requests correctly, or not, can have an impact. In 2021, former Councilwoman Brenda Mead filed a lawsuit against former Mayor Andrea Oakes after not receiving documents she requested from the mayor. Oakes then had five days to respond to Mead’s request, but she did not do so. Although the court ruled that Oakes did not make a FOIA violation willfully, it also ruled in Mead’s favor. Council elected to use taxpayer money to cover the $4,050 for fees and costs incurred by Oakes in defending the case and $3,374 for the judgment awarded against Mayor Oakes in that case.

The presentation was information heavy but full of things public servants need to know to effectively do their duties. Blair acknowledged this and thanked them for getting involved anyway.

“The reality is I could stand here for five hours and go through intricacies, or I could do [30] minutes and tell you what you really need to know,” Blair said. “I think you’d probably want that, rather than the law school lecture. … I want to thank you. It is great to have public servants who have volunteered to help our city grow and prosper.”

This article originally appeared on Staunton News Leader: Open meetings and FOIA critical to a transparent government