Trapped by Markets and Voters, Sunak Faces ‘Impossible’ Budget

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

(Bloomberg) -- UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak faces an extraordinary balancing act in his autumn budget next week. He needs to appease financial markets with a package of spending cuts and tax increases, while also winning over disgruntled voters.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Musk Warns Twitter Bankruptcy Possible as Senior Executives Exit

Bankman-Fried’s Assets Plummet From $16 Billion to Zero in Days

Sam Bankman-Fried Fooled the Crypto World and Maybe Even Himself

Elizabeth Holmes Asks for a Lenient 18-Month Sentence at Home

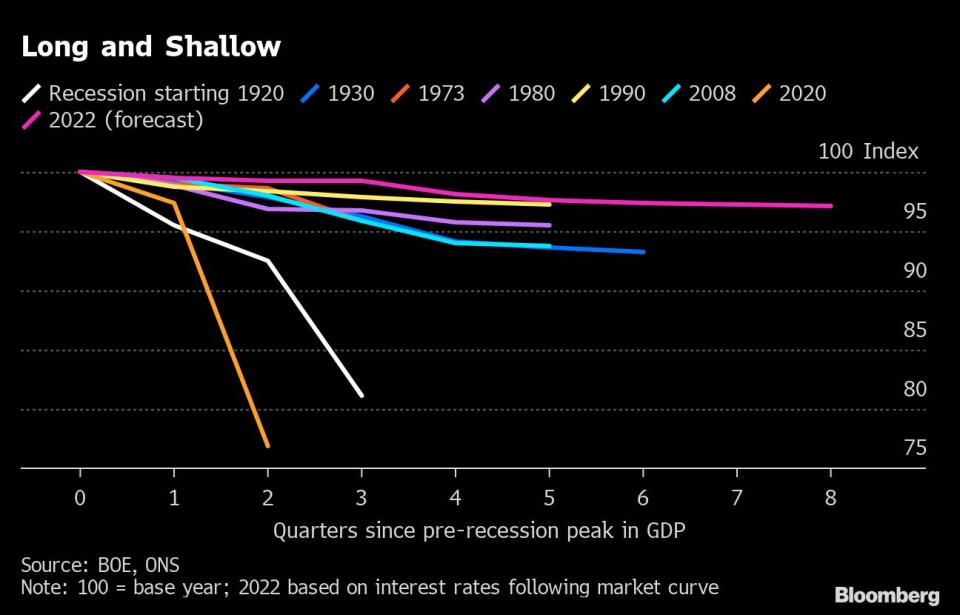

Sunak and Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt are currently making final decisions on the more than £50 billion ($58.3 billion) of economic retrenchment to be announced on Nov. 17. Hunt will deliver the statement against a grim economic backdrop for the UK, with the Bank of England hiking interest rates and warning the country is heading into a recession that may destroy at least half a million jobs.

It’s set to be a moment of high-risk politics that could define Sunak’s fledgling premiership. Hunt is keen to restore the UK’s credibility with investors still scarred by Liz Truss’s short stint in office with a strong message of discipline and economic caution. But Sunak knows that he will be punished at the ballot box if he goes too hard with austerity, adding pressure on Britons already enduring a record squeeze on living standards.

“It’s almost impossible to please both constituencies,” said Helen Thomas, a former adviser to ex-Chancellor George Osborne and CEO of BlondeMoney, an economics consultancy. “You’re looking at a fiscal tightening which is very rarely welcome from voters. It’s really tricky.”

While Hunt might ordinarily want to use government spending to prop up the British economy heading into a downturn, he and Sunak are worried about exacerbating double-digit inflation, which would prompt further painful interest rate hikes by the BOE. That in turn would increase the government’s debt servicing costs and hurt voters through higher mortgage payments.

“The elephant in the room is that part of the solution to bringing down inflation is to reduce demand in the economy,” said Kitty Ussher, chief economist at the Institute of Directors and a former Treasury minister under ex-premier Gordon Brown. “The strategic choice for the government is whether they accept that, or whether they think that’s politically unpalatable.”

Hunt has already reaped a market dividend with his cautious approach, bringing down gilt yields by reversing the massive tax cuts introduced by Truss that sent bond yields skyrocketing. Yet his and Sunak’s political challenge is selling a deeper package of austerity to a disgruntled public accustomed to state support during the pandemic. Neither he nor the prime minister have the authority that comes from winning a general election and neither are natural political salesmen, Thomas said.

The next general election isn’t expected until 2024, but with the Tories far behind Labour in the polls, the enormity of the task facing Sunak is well understood in 10 Downing Street. Will Tanner, Sunak’s recently-appointed deputy chief of staff in charge of policy, wrote a pamphlet for his Onward think tank before he joined No. 10 in which he candidly admitted: “It may be too late to save a majority at the next election.” Instead, Tanner wrote, Sunak’s aim should be to “avert a landslide defeat” from which the Tory party might “never recover.”

Sunak’s situation has echoes of the dilemma faced by the Tories in 2010, when then-Chancellor Osborne rolled out a wave of austerity in the wake of the 2007-2008 financial crisis. Though unpopular at the time, the Conservatives went on to win a surprise parliamentary majority in 2015. Sunak met with Osborne last month to discuss the autumn budget and Rupert Harrison, Osborne’s former chief of staff, is on a newly-created panel of experts advising Hunt.

The difference this time is that Sunak is having to roll out austerity amid rising interest rates and high inflation, headwinds that weren’t an issue for former Tory premier David Cameron. Also, Cameron became prime minister on a mandate to curb public spending and could blame the state of the economy on the previous Labour government. Sunak, by contrast, has inherited the premiership without a public vote following a 12-year Tory stint in office.

Hunt is likely to lean on a range of stealth tax increases to fill the government’s fiscal hole alongside real-terms cuts to departmental budgets. His plans include cutting various tax thresholds and allowances -- which will drag more people into paying tax without needing to increase headline rates -- while also expanding a windfall tax on energy firms and freezing foreign aid. His challenge is picking a mix that does least harm to the real-world economy while still raising revenues for the Treasury, the IoD’s Ussher said.

In total he’s looking for savings and revenue raises worth between £50 billion and £60 billion, made up of up to £35 billion in spending cuts and up to £25 billion in tax hikes, according to an official familiar with the matter, speaking on condition of anonymity because no final decisions have been made.

Another area at risk is spending on infrastructure projects. Days before joining Sunak’s government, Chief Economic Adviser Douglas McNeill told the BBC Today program that spending cuts should be targeted at capital expenditure, such as roads and rail projects, because they can be squeezed “without people noticing immediately.” A Whitehall official cautioned that cutting spending on roads and bridges by stealth would be a betrayal of the Tory agenda of leveling up poorer regions of the UK. Shevaun Haviland, one of the UK’s top business executives, also cautioned against cutting infrastructure spending, saying such projects will help power Britain’s recovery.

Sunak also has to be wary of his faction-ridden backbenches, knowing that a rebellion from just 10% of his MPs would be enough to block parts of his program in Parliament. With Labour’s large poll lead making many Conservative MPs fearful for their seats at the next general election, he has to be careful with measures that would hurt crucial sections of the Tory voting base, said Adam Hawksbee, interim director at Onward.

“There’s a really difficult tight-rope to walk,” Hawksbee said, citing the need to protect voters in the traditionally Labour-voting northern heartlands that swung to the Conservatives in 2019, while also avoiding antagonizing the wealthier core vote in Britain’s rural south. “It’s going to have to be that each takes a little bit of pain, but neither takes too much.”

--With assistance from Andrew Atkinson.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

Americans Have $5 Trillion in Cash, Thanks to Federal Stimulus

One of Gaming’s Most Hated Execs Is Jumping Into the Metaverse

A Narrow GOP Majority Is Kevin McCarthy’s Dream/Nightmare Come True

Peter Thiel’s Strategy of Pushing the GOP Right Is Just Getting Started

Meta Investors Are in No Mood for Zuckerberg’s Metaverse Moonshot

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.