How Trashy Creatures Thrive in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch

There’s probably no more embarrassing example of our impact on the planet than the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. This massive collection of plastic waste and inorganic debris spans more than 617,000 square miles—or twice the size of Texas. While we humans shoulder the brunt of the blame when it comes to its creation, part of the reason it’s there is because of the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (NPSG), one of the world's five main oceanic vortexes where several ocean currents converge.

The Garbage Patch is a damning example of our excessive waste. However, new research shows that it might actually be integral to a burgeoning ecosystem that lives in literal trash.

Researchers in the U.S. and U.K. published a study Thursday in the journal PLOS Biology where they looked into the incredible amount of sea creatures that live amongst the plastic waste of the Garbage Patch. They discovered that there was a much greater abundance of creatures that live within the Patch than on its periphery.

However, the authors were quick to note that this isn’t because the Garbage Patch is necessarily conducive to life—but rather, life is persisting in the trash anyway. (Hey, aren’t we all?)

Put it another way: Life, uh, finds a way.

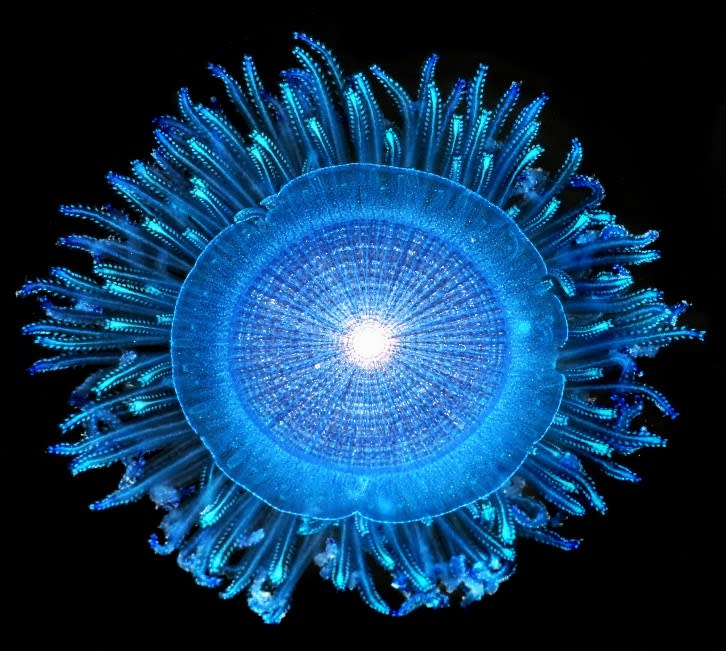

Blue button jellies, known by their scientific name Porpita, float on the ocean’s surface using a round disc, and drift where the current takes them.

“The ‘garbage patch’ is more than just a garbage patch,” Georgetown University marine biologist Rebecca Helm, who is the lead author of the paper, said in a statement. “It is an ecosystem, not because of the plastic, but in spite of it.”

The study’s authors actually drew upon samples of the Garbage Patch collected during the Vortex Swim, a 80-day long distance swimming challenge conducted by French swimmer Ben Lecomte where he swam 350 nautical miles through the patch to raise awareness about microplastic pollution in the oceans. The journey began June 2019 in Honolulu, Hawaii and ended in August 2019, and followed a route that was modeled to have the highest concentration of garbage through the patch.

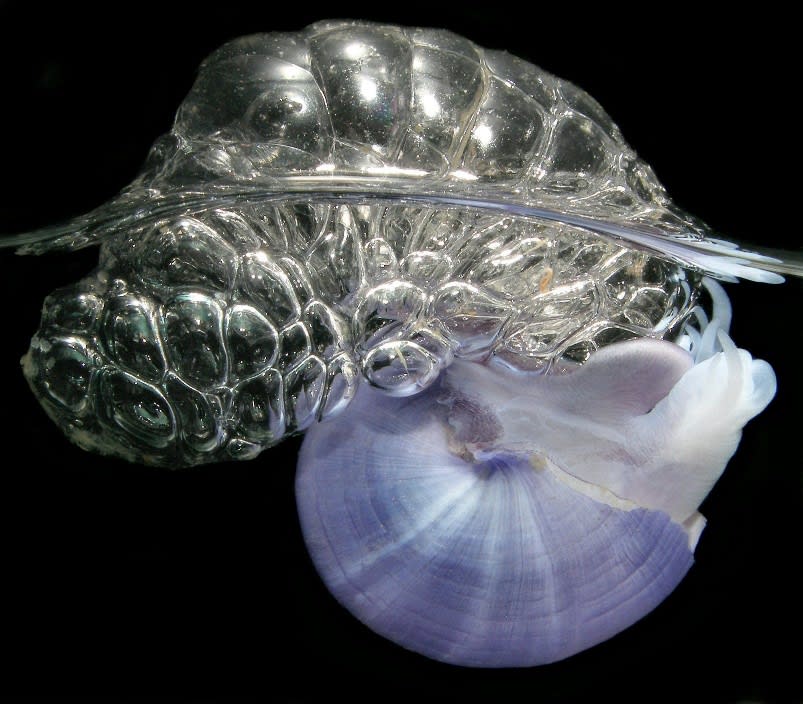

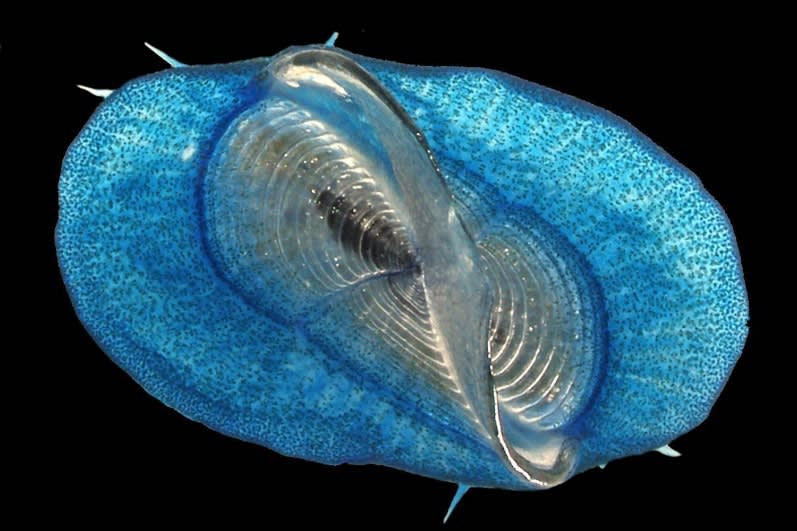

Using the samples gathered by Lecomte and his sailing crew, they discovered that the concentration of plastic waste was positively correlated with higher concentrations of three floating sea creatures: sea rafts, blue sea buttons, and violet sea snails. These creatures are also known as neustons, which describe lifeforms that live at the very surface of water.

The violet snails Janthina construct floating bubble rafts by dipping their body into the air and trapping one bubble at a time, which they then wrap in mucus and stick to their float.

It’s not because these creatures just love living in trash like so many humans in their twenties, but rather the same NPSG that gathers the garbage also shepherds the creatures into the area where they feed, mate, and proliferate in their plastic trash ecosystem. The study’s authors also discovered evidence that sea creatures such as sea skaters lay their eggs on the plastic trash.

While it might seem great that life is able to survive despite the seemingly unideal environment, it actually poses a great danger to creatures that eat neustons such as sea turtles and albatrosses. These creatures frequently ingest sea plastics in the search for food. With one vital food source literally mired in the world’s largest patch of plastics, it only increases the chances that they’ll end up eating the trash too.

The researchers hope that their study helps inform future ecological research into the life that’s seemingly thriving in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, while also making those within the high sea industries aware of the delicate ecosystems that they work within.

If nothing else, you can take comfort in the fact that even in the most disgusting environments, creatures are still capable of making their way through life. So, maybe your roommates who won’t wash their dishes aren’t so bad after all.

Velella. These blue jellies, known as by-the-wind sailors, drift with the wind using a special living sail.

Got a tip? Send it to The Daily Beast here

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.