These people treated Sars, Ebola and swine flu: what is their advice on beating coronavirus?

As Europe struggles to contain Covid-19, some of the country's leading health and science experts reflect on the previous outbreaks they have witnessed on the frontline and the lessons that can be learned to prevent its spread.

Sars: Dr Simon Mardel, OBE

I was a clinician with the World Health Organisation when the SARS virus was discovered in 2003. I had already been involved in previous outbreaks like Ebola, Marburg and Lassa fever (during the Sierra Leone civil war in 1997) and was focused on how to improve treatment but at the same time stop the spread of infection in health care.

Health professionals are on the frontline of such outbreaks. Over the years many colleagues have ended up contracting diseases, often with tragic consequences. SARS - like Ebola - was spread through healthcare facilities. I’m really worried about the potential of Covid-19 to do the same.

During severe outbreaks staff are forced to work in extreme circumstances and can miss out on essential steps of protection. I remember a nurse I once saw crying into her gloved hands on an Ebola ward, grieving for a friend she had cared for during her last hours of life; or a doctor who performed a difficult procedure on a nurse with Lassa fever in a dimly-lit, overcrowded ward with no bin to store his medical waste.

In order to combat these outbreaks we also need to follow the standards of infection control that are supposed to apply to every single patient in health care - I think this will be the biggest threat to the UK during this outbreak.

These include the so-called ‘standard precautions’ that include avoiding contact with patients’ body fluids, preventing the spread of fluids or droplets and adhering to strict standards of cleanliness of equipment and rooms. Such measures may sound simple and are universally agreed, but regularly ignored by busy staff (including in the UK).

As a result of SARS proper infection control measures kicked in more effectively in those countries who lost staff. The likes of Hong-Kong, Singapore and Canada, were described as having been “burned by SARS” and adopted new standards in response.

The challenge now is for the UK to implement such standards quickly across every branch of healthcare. Otherwise who knows what might be the eventual impact of Covid-19?

Swine Flu (H1N1): Sandra Mounier-Jack, associate professor in health policy at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

During the H1N1 outbreak I was a researcher focusing on pandemic preparedness. I had been contacted by the House of Lords to contribute to an inquiry about preparedness in the wake of avian flu and was working as a specialist advisor to the Cabinet Office. Then, in the middle of the inquiry, H1N1 happened.

The first cases were in April 2009 in Mexico. It seemed severe at the beginning with potentially high numbers of fatalities but very quickly it became quite evident the disease was not as severe as initially feared.

The virus circulated very quickly in the UK but proved to be quite mild so containment wasn’t really necessary. Also everybody knew a vaccine would come along quite quickly and in the meantime we had anti-virals to limit the impact.

With coronavirus we don’t have that weaponry. Another concern is that H1N1 started in April at the end of the influenza season which really helped the response. It is not yet proven whether warmer temperatures will affect the spread of coronavirus – there is a lot we still don’t know.

Ultimately H1N1 led to nearly 460 deaths in Britain but seemed to particularly affect children and pregnant women. The number of people hospitalised was actually very small but even then it put hospitals under pressure. At one point every paediatric critical care bed was in use.

With coronavirus, the affected population is different with a very high fatality rate among over 80s and a need for intensive care spaces.

There is a risk of the virus being spread around hospitals and care homes are another worry. The H1N1 outbreak emphasised to us the need to be flexible in our response – and certainly coronavirus will test that once more.

Ebola: Dr Oliver Johnson, King’s College London

In 2014, I was working in the main teaching hospital in Freetown, Sierra Leone, leading a small team from King’s College London working to strengthen the health system. Ebola had started over the border in Guinea and my first memories are knowing the outbreak was heading towards us and thinking how are we going to get prepared?

In the early months of the outbreak, almost all of the staff who were infected with Ebola at our hospital died. One face that stays in my mind was an amazing young nurse called Hajara Serry, who we were supporting to improve emergency care. One day I saw her slumped in her chair with a yellow glaze to her eyes that we had come to recognise as ‘Ebola eyes’.

I remember putting her in the ambulance late on Saturday. We both knew she was almost certainly going to die, and that my farewell would probably be the last words she would ever hear – she didn’t survive the journey. I’m still haunted by the knowledge that we had failed to protect her.

In the early days of the outbreak, officials thought the best thing to do was to downplay things. It’s hard to imagine the unimaginable and there is this innate desire not to worry people. That’s fine for a few weeks but then when the virus comes you haven’t laid the groundwork.

I worked with England’s current Chief Medical Officer Chris Witty during the outbreak and the approach he is taking with coronavirus, of being honest and urging people to get prepared, is definitely the way to go.

But, as with Ebola, it is now already too late to get fully prepared. The first line of defence in any outbreak is a strong healthcare system and the NHS has been underfunded for too long, pushing it to breaking point.

This idea that any country can suddenly find more doctors or wards overnight is fanciful – those things take time and investment to build.

We’re going to have to deal with the fact that there are a lot of unknowns with coronavirus.

The public needs to be informed – there can’t be a disconnect between communities and the public health experts. We need to get organised and become part of the response, caring for our neighbours and taking care not to spread misinformation or fake news. All of us need to step up.

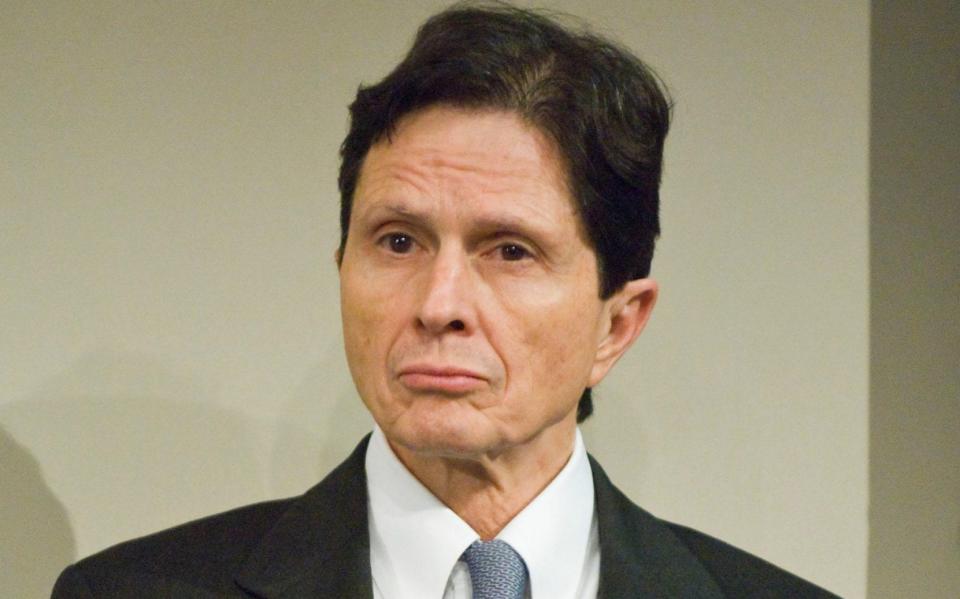

MERS: David Heymann, professor of infectious disease epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

I was chairman of Public Health England (PHE) in 2012 when a man who had recently arrived in London from the Middle East was taken to hospital with a severe respiratory infection. PHE did genetic sequencing on the virus and matched it to a similar infection and genetic sequence that had been reported to a public discussion forum a few weeks previously by an Egyptian doctor working in Saudi Arabia.

It proved to be Britain’s first case of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome - a respiratory illness caused by the MERS coronavirus that is believed to infect camels which then spread it to humans.

The patient was isolated immediately in St Thomas’ Hospital and no further transmission occurred. Since 2012 there have been five cases of MERS confirmed in England and they have caused no outbreaks. During this same period nearly 1,500 people suspected to have the infection were tested in UK laboratories.

This PHE experience of it shows the importance of strong infection control in hospitals, while other countries such as South Korea have suffered large MERS outbreaks when sub-standard infection control practices occurred in health facilities.

With all emerging infections there are many concerns, but two which particularly stand out are that health workers are at great risk of infection and that all humans are susceptible because they have not experienced previous infection that develops antibody protection.

Trial pandemic: Dr Hannah Fry

Last week, the first case of a patient being infected with Covid-19 within the UK was discovered in Haslemere, the small commuter town just off the A3. It was, to me especially, an eerie twist of fate: two years ago, Haslemere was at the heart of another pandemic, this time a fictional one I and a team of experts created as part of an experimental documentary.

The idea was simple. Using a newly-built app, we would ‘infect’ the good people of Haslemere, then track where they went and who they interacted with over the course of a day, allowing us to view how quickly a potentially deadly virus spreads.

At the time I remember saying it would be a case of “when, not if” Britain is hit by a deadly pandemic. Whether Covid-19 is that pandemic remains to be seen, but our findings in 2018 were certainly telling.

We saw there are certain places where transmission is more likely to occur, like train stations, medical centres and high streets. Our ‘super-spreader’, in fact, was a worker in a hardware shop.

Those findings weren’t entirely surprising, but the model also showed how simply the contagion could be slowed, especially by hand-washing. It is the main piece of advice being issued at the moment for a reason

The data told us so: our simulation predicted that the number of people who caught our ‘virus’ within 100 days could be slashed from 42 million to 21 million – but only if people washed their hands an extra five to 10 times a day.

Ours was ‘just’ a data model, of course, but those findings are now being used to help organisations tasked with dealing with Covid-19. We knew it would be useful; I didn’t quite think it would be so soon.