The Treaty of Cambridge: 60 years later, a legacy of hope and still a work in progress

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Cambridge native Dion Banks carries with him the legacy of the Civil Rights Movement and its intersection with the city his family has called home for generations.

His car’s trunk is filled with photos of civil rights leaders who walked the streets before he was born and a cutout copy of the 1963 Treaty of Cambridge, a landmark agreement between the city’s residents and the federal government.

But Banks, a marketing vice president by trade and co-founder of the nonprofit Eastern Shore Network for Change, sees the treaty, signed 60 years ago Sunday, as far more than words on a page.

“It provided hope,” said Banks, in an interview, standing outside the Bethel A.M.E. church that served as a headquarters for those clamoring for change during the 1960s. For some Cambridge residents who hadn’t had steady electricity or indoor plumbing, the treaty helped lay the foundation for amenities most Americans take for granted.

The three-page document — signed by the United States attorney general, the city’s mayor, state officials and civil rights advocates — also fit the small Eastern Shore locale back into the pages of history, making the city a reference point at that summer’s March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. put forth the dream that still rings in society today.

Birmingham comes before Cambridge

Four months before King spoke from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial at the march in Washington, D.C., he wrote from the confines of a jail cell in Birmingham after being arrested for protesting segregation on Good Friday.

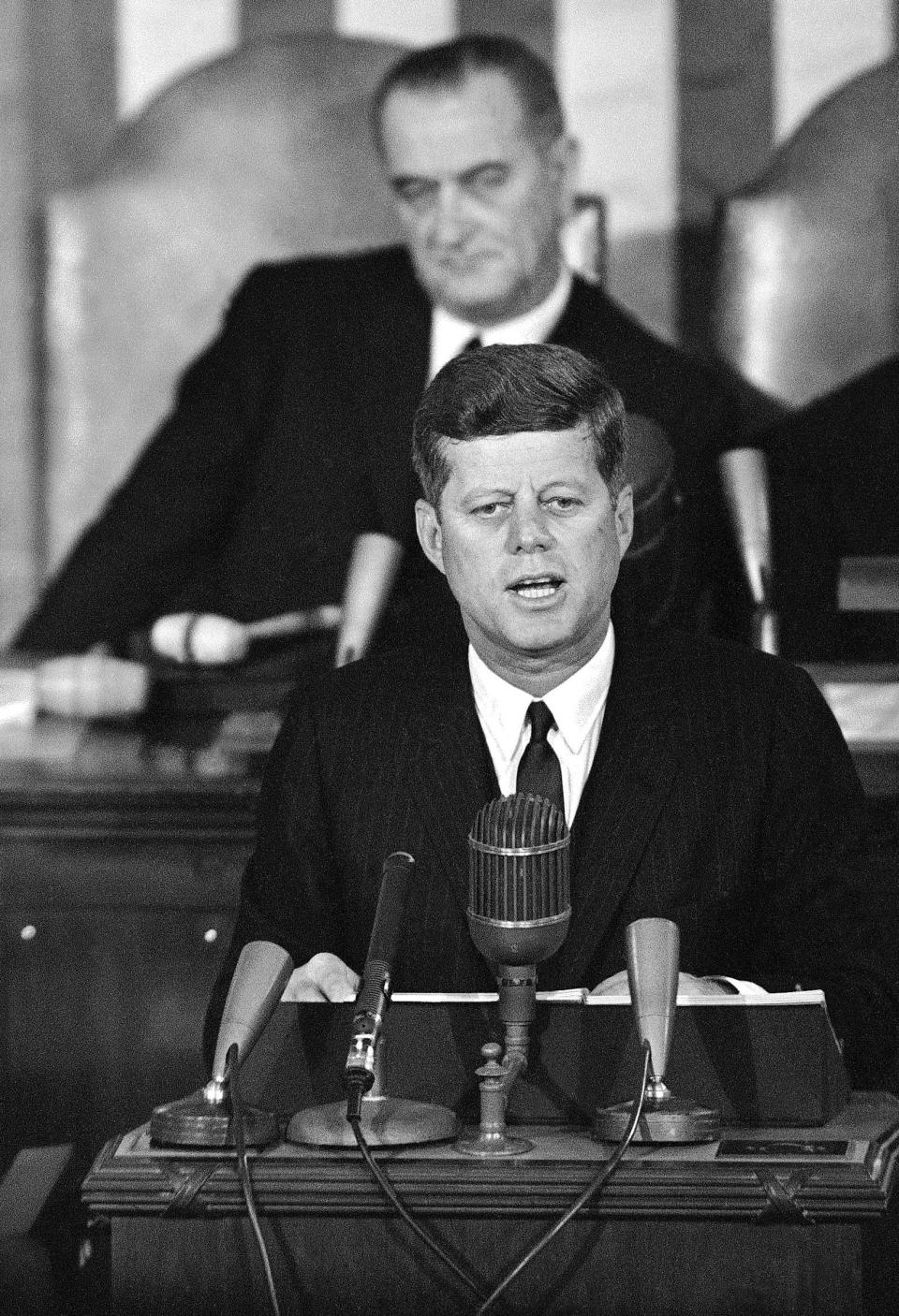

His arrest combined with the thousands of schoolchildren who marched, braving dogs and firehoses in the Alabama city, garnered international attention and catapulted President John F. Kennedy’s administration into the midst of a national crisis.

“The Kennedys were in the middle of a transitional moment for America,” said Harry Belafonte, the legendary singer who died earlier this year, during a 2018 documentary interview. Belafonte was right there in the middle of the transition, too, pushing the administration forward on civil rights.

He called U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, the president’s brother, on King’s behalf during the reverend’s Birmingham imprisonment, and later participated in a critical meeting between Black activists and Robert F. Kennedy in May of 1963, which would change the country.

Less than a month after the meeting, President Kennedy, at the urging of his brother, was on television, speaking forcibly in favor of equal rights and opportunities for African Americans.

Cambridge protests continue despite presidential speech

But presidential proclamations, regardless of how passionate, did little to prevent the ongoing protests that persisted on the pavement across the country in the streets, including in Maryland, where demonstrations had been taking place in restaurant seats since the dawn of the decade.

William “Bill” Hansen first came to Maryland from his hometown of Cincinnati, Ohio, where he attended a Catholic university. He befriended an African American peer playing basketball and eventually helped to form an interracial council on campus. This led to more organizing activity.

Hansen, who is white, met Baltimore native Reginald Robinson, who is Black, during sit-in protests at restaurants along Maryland’s portion of Route 40. After arrests in Baltimore in 1961, the two decided to take action to change a part of the state with the worst racial reputation — the Eastern Shore.

More: Racism along this historic Maryland route was rampant in 1961. Then students helped ignite change.

“Once you crossed that Chesapeake Bay Bridge, which was very new then,” said Hansen, of the bridge that opened in 1952, “you were in Alabama.”

Robinson, who spent the early part of 1961 working on voter registration in Mississippi in the Deep South, put the racism of Maryland’s Eastern Shore and Alabama on an “equal scale.”

“That’s what the reputation was,” said Hansen, in a May interview. “That’s why we came there.”

The two, along with eight others, held a sit-in at City Restaurant in Crisfield, a remote waterfront city that was the hometown of the state’s then-Gov. J. Millard Tawes. They were arrested in Crisfield on Christmas Eve 1961 and jailed in Princess Anne, the Somerset County seat.

Their bail bondsman, Frederick St. Clair of Cambridge, suggested they go there next. It would be in the abolitionist Harriet Tubman’s home county where the threads of history converged.

Threads converge in Cambridge

Hansen and Robinson entered a city struggling on Race Street and stayed with the St. Clairs, which included Herbert, the city’s first Black councilmember and a wealthy businessman.

St. Clair’s assessment of the city in 1963 did not contradict the recollections from 60 years later.

“It's hard to believe that Washington, D.C., is only seventy-five miles away-we live like the Deep South,” said Herbert St. Clair, in a 1963 article. “There are parts of the Eastern Shore where Negroes still get off the sidewalk and stand in the gutter when a white person walks past.”

GRANDFATHER OF GOSPEL: 'Grandfather of Gospel': Eastern Shore birthplace to commemorate the Rev. Charles Tindley

Downtown’s main road, ironically “Race Street,” divided the white and Black sections of town, said Donna Richardson Orange, a Cambridge native and cousin to the bail bondsman St. Clair.

“At one point there were no Blacks working on Race Street,” said Richardson Orange, now a septuagenarian, in a July interview. Employment prospects weren’t much better at the time for Blacks off Race Street either.

Phillips Packing Company, which employed thousands of Cambridge residents and supplied rations for World War II troops, dwindled after the war, eventually closing its doors in the ’60s. Those doors slammed harder for those in the Black community.

In 1963, the unemployment rate for whites stood at about 7 percent; for Blacks the rate was nearly four times higher, according to a document in the state’s archives.

Only 3 percent of Cambridge’s total population of the age of 25 or older was college-educated, and only 28.7 percent had completed high school, contrasted with the statewide figure of 41.7 percent, according to a 1963 article.

It was in that environment that Hansen and Robinson began their organizing work, primarily with the city’s young people. Hansen described being beat up on a picket line by a young white man while leading a protest of one of the six segregated restaurants in nearby Easton.

Hansen didn’t hit back. State troopers intervened on Hansen’s behalf and broke up the melee. No arrests were made. An aggressor, white Cambridge native Eddie Dickerson, was shocked. So much so that he went to the church later that night to find out why Hansen had not hit him back.

“We honestly think that love can overcome hate,” Hansen told Dickerson, as recorded in the 1963 article “Why Didn’t They Hit Back?” produced by the Congress of Racial Equality.

Robinson worked as a field secretary in Cambridge for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC. Hansen would soon be relocated to another SNCC project in Albany, Georgia, as a field secretary, but not before he was beaten again, thrown out of the Choptank Inn, and arrested.

“I believed in the American dream,” said Hansen, now a professor of politics at the American University of Nigeria in Yola. He’s missing a few teeth after beatings endured in the civil rights era. “The policy that we pursued in Cambridge was to hold a mirror of America up to itself.”

That mirror and the images of America

The image of America in that mirror was unsightly in 20th century Cambridge, as it would have been a century prior, standing near the Dorchester County Courthouse, a site where the enslaved were taken up High Street from the waterfront, sold at auction, and where Tubman did a rescue.

Today, a statue of Tubman, called “The Beacon of Hope,” unveiled last year, stands, marking the spot. About 30 yards away, another marker indicates the spot where John Kennedy spoke during the presidential campaign of 1960. His brother Robert served as his campaign manager.

The twin markers miss the moment that the two brothers help etch into the city’s civil rights history. Gloria Richardson, whose daughter Donna brought her into the demonstrations before she became a civil rights leader in her own right, set the record straight on who should get credit for the 20th century chapter of the civil rights story. It wasn’t primarily the Kennedys or King.

“It wasn’t Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. who turned Cambridge around,” said Richardson, in a book that compiled accounts of women involved with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. “It was all the local students who were out there laying their lives on the line.”

Two of those students, Black teenagers and schoolmates of Donna Richardson Orange, Dwight Cromwell and Reva “Dinez” White, were arrested for praying peacefully outside of a segregated bowling alley on Memorial Day 1963 and sentenced to time in state facilities on June 10, one day before Kennedy’s civil rights speech.

“It bothered me,” said Richardson Orange, of seeing her 15-year-old schoolmates sentenced. “It bothered a lot of us.”

Over a dozen Blacks were arrested for protesting the arrests outside of the Courthouse, according to subsequent reporting. The day of the Kennedy Oval Office speech, two white men were shot in Cambridge and three businesses destroyed. The day after the speech, another couple of businesses — both Black and white — were destroyed by fire.

Hundreds met at the Courthouse that week in a racial standoff, with police separating the Blacks and whites in an attempt to maintain order. The next day, Gov. Tawes called in the National Guard.

National Guard comes to Cambridge

Coming so soon after the Birmingham protests and President Kennedy’s speech, the images of racial tumult and the Guard in Cambridge put the first-term Kennedy administration in a bind.

“The Kennedys were running around the world as the ‘great human rights people’ when there was warfare in the streets of Cambridge,” said Gloria Richardson, in her account in a book.

She would go to Washington multiple times that summer as chair of the Cambridge Non-Violent Action Committee, including to a July 9 White House meeting where the president laid out his agenda to address the racial issues in the country. But the situation in Cambridge still simmered.

The same day as the White House meeting, the Cambridge native Eddie Dickerson, who had beaten Hansen 18 months earlier, had his photograph appear in newspapers across the country. The reformed Dickerson had an egg broken upon his head by a white restaurant owner while he knelt and sang civil rights songs next to Black protesters.

The moment was captured by the press and Dickerson endured the indignity without reciprocating the violence. He was not the only one pictured pushing away from violence.

In a now iconic photo, Richardson is seen walking through the streets of Cambridge and putting her hand up to block a National Guardsman’s bayonet while a crowd looks on.

In her writing, Richardson recalls a different fight: the Cambridge contingent “battling back and forth with Robert Kennedy” during those weeks.

“They called us to Washington for this meeting to try and settle things,” said Robinson, in a May interview, the only living witness to the July meeting that took place in at the U.S. Department of Justice in D.C. sixty years ago.

The meeting in Washington, D.C.

Richardson came prepared, if not elated. She had earlier designed a door-to-door survey of Cambridge’s Black community to find out exactly what people in the community wanted.

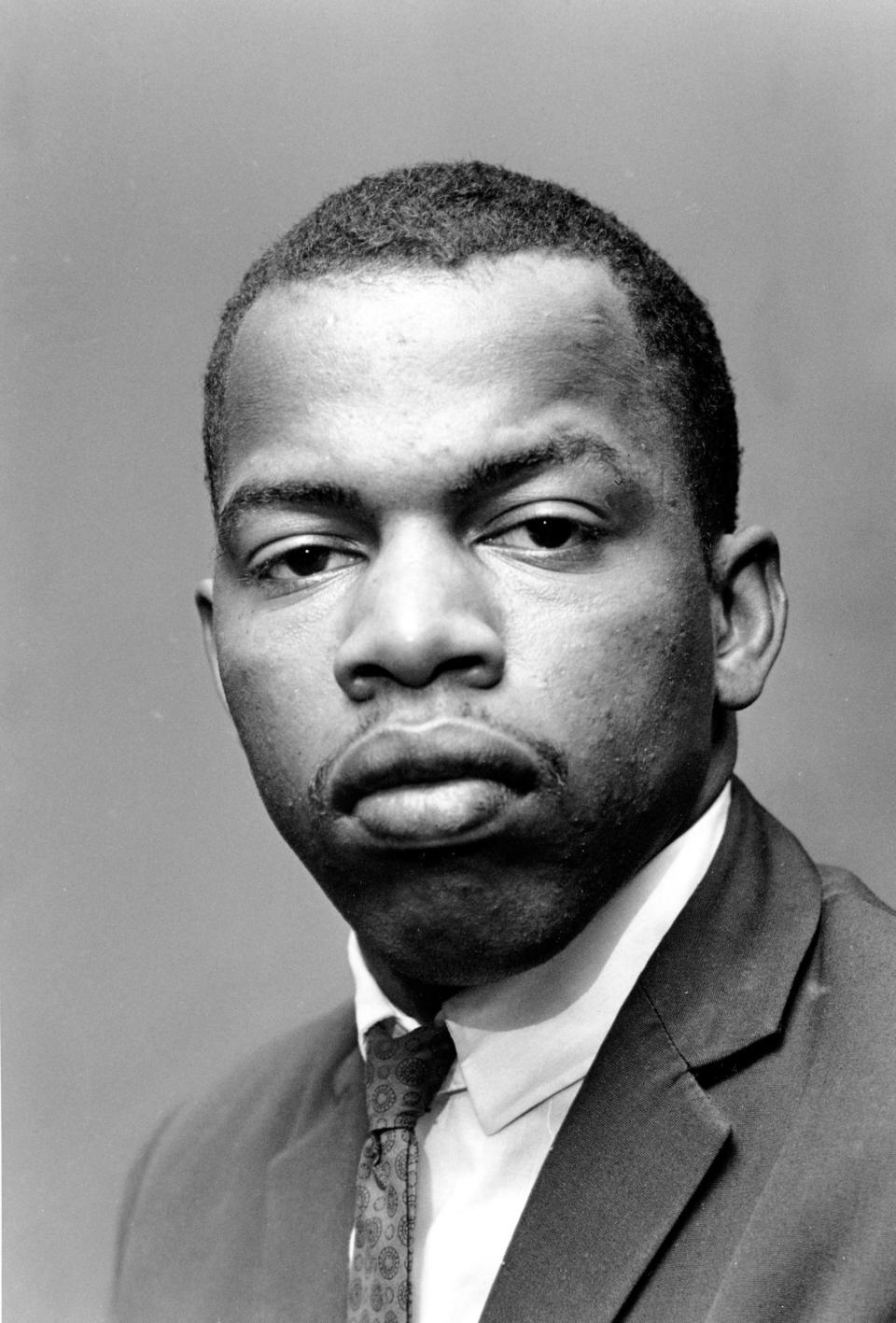

“It was not a happy occasion for Gloria,” said John Lewis, the then-national chair of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, who attended the meeting and recalled it in his memoir. Richardson’s lack of joy may have stemmed from a distrust of “the scene,” as Lewis indicates, or from the severity of the situation as she had learned from her survey and her life’s experience.

The answer was not desegregation alone. Along with high unemployment, 40 percent of the city’s homes had no inside toilet facilities, she found, in a report that was sent to the Kennedys.

Robinson, the Cambridge field secretary for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, recalls what was discussed that day as “the whole gamut,” including jobs, housing and schools. He also noted the meeting was the first occasion “the federal government decided to talk to us.”

“That was meeting was so important because it was one of the first times that … they had attempted to call us in at that level,” he said. “I don’t know of another meeting such as that.”

By day’s end, an agreement had been reached. Employment, desegregation of public places and schools, and housing for the Black community were all addressed in the agreement.

WES MOORE'S 1ST 100 DAYS: Maryland moves forward with Gov. Wes Moore during first 100 days as bills get signed

Lewis, a native Alabamian who marched alongside Richardson in Cambridge, called the agreement a “great step forward for Cambridge” for both Blacks and whites during a press conference on July 22 at the Justice Department.

“We look forward that Cambridge will lead the way in the State of Maryland as a new city, as a new community, striving to solve the problems that we all face in this nation,” said Lewis, according to a transcript of the press conference on file at the Kennedy Library in Massachusetts.

After-word: The March on Washington

Either way you look at it, Cambridge got one word in at the Lincoln Memorial the next month, August, at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom held in D.C. along the national mall.

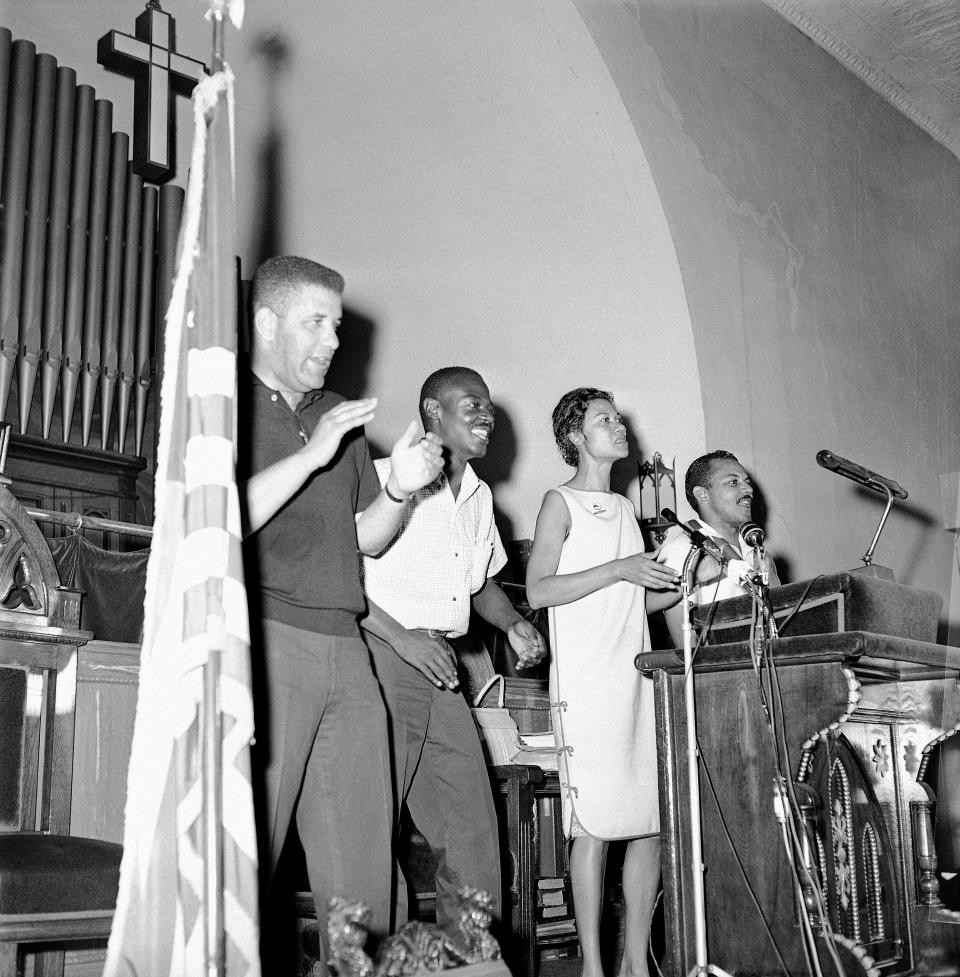

Despite the smiling photograph of Robinson next to Richardson taken at Bethel A.M.E. Church in Cambridge on the day that the agreement, or Treaty of Cambridge as it came to be known, was signed, the story wasn’t yet finished. Gloria Richardson and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee wanted the Kennedy administration to keep its promises.

In an indication of the gender inequity of the day, six Black women, including Richardson, shared a small section of the march program, while more than six men, Black and white, gave remarks.

“Hello,” was the word Richardson managed to say into the microphone that day before the mic moved on to another speaker, the meaning of her presence in that moment not yet recognized.

“Cambridge” was not in the original text of the 23-year-old John Lewis speech at the Washington march. In a day-of change to keep unity between civil rights organizations, Lewis changed his speech, making it less critical of Kennedy’s legislation and referencing Cambridge.

“We will march through the South, through the streets of Jackson, through the streets of Danville, through the streets of Cambridge, through the streets of Birmingham,” said Lewis, later a U.S. Congressman representing Georgia, “but we will march with the spirit of love and with the spirit of dignity that we have shown here today.”

Richardson Orange, the Cambridge teen in attendance at the peaceful march that day, went home, but she and her mother would soon be walking in a changed country with new leaders.

Leaders leave, new leaders emerge

This month, standing across Pine Street from the St. Clair business where Richardson worked, Dion Banks waves back to a lot of people driving by, including one he points out as the city’s former mayor, Victoria Jackson-Stanley, the daughter of Richardson’s lieutenant from the ’60s.

Jackson-Stanley, the city’s first African American mayor who served from 2008 until 2021, is representative of a different Cambridge than the one Hansen and Robinson came to back in 1962. (A sign was also installed in Crisfield last month commemorating the pair’s actions in that city.)

After President Kennedy was killed in November 1963, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed, desegregating all public accommodations throughout the country, including in Cambridge, where despite the signed agreement, citizens voted against requiring desegregation the previous year.

“When it comes to the legacy,” said Banks, of the Treaty of Cambridge,“one thing that happened when Gloria left was there was no one that really stepped into the position of leadership.”

Richardson moved to New York in 1964, John Lewis was voted out of his position with SNCC in 1965 as “Black Power” became popularized, and H. Rap Brown, who became chairman of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee in 1967, came to Cambridge later that year.

Brown, pictured today with Richardson on a mural on the side of a Pine Street store, was in town when a significant section of the Black community burned after an altercation with police in ’67.

“The press likes to say ‘the Rap Brown riot’ and conveniently ignore everything that came before it,” said Richardson, in a 2017 article in Baltimore magazine. “I mean, it’s not like there wasn’t plenty of activity and attention to what we were doing just a few years earlier.”

“But all of that tends to be forgotten,” said Richardson, who is depicted in another mural image, standing next to Tubman, which since 2017 greets visitors crossing a bridge into Cambridge.

The children, Cromwell and White, eventually released from Maryland facilities through the agreement and Robert Kennedy’s intervention with the state, have faded into history’s pages.

Housing built because of the Treaty of Cambridge still stands

Six decades later, the housing that was built in Cambridge as a result of the 1963 agreement still stands, albeit with an updated façade and a gate installed around the federally owned apartments.

State Delegate Sheree Sample-Hughes, who grew up in Salisbury in the late ’70s and ’80s and now represents the area in the state legislature, has reached out to the state’s federal delegation to ensure the properties that are federally owned are “up to par” with “proper living conditions.”

“We need to meet with the management companies that are overseeing these properties,” she said. During a recent ride along with the Cambridge Police Department, Sample-Hughes, in a way reminiscent of Richardson, informally surveyed the children in the area, asking their wants.

One boy asked for a swing set.

The day after the interview, the delegate was scheduled to meet with representatives from the Cambridge YMCA regarding where the organization is thinking about building in the future.

“We should already to some degree have the map and be able to expand upon it,” said Sample-Hughes, currently the House of Delegates Speaker Pro Tempore. “We’ve come a long ways.”

“There’s still more to be done,” she said, “but we can only do it if we do it systematically and with a plan.”

Dwight A. Weingarten is an investigative reporter, covering the Maryland State House and state issues. He can be reached at dweingarten@gannett.com or on Twitter at @DwightWeingart2.

This article originally appeared on Salisbury Daily Times: Treaty of Cambridge: How it came amid strife in Civil Rights Movement