Tri-Cities advocates already seeing homelessness surge as federal aid dries up

Tri-Cities housing advocates are already seeing a surge in people at risk of falling into homelessness after pandemic-related funding ended for local programs last month.

The funding, which was used to boost homelessness prevention and housing programs in the Tri-Cities and across the nation, largely ran out this summer. What hasn’t gone away is the need for the programs.

Recent data from Washington state shows just how effective homelessness prevention programs have been at reducing homelessness in Tri-Cities.

Programs that saw boosts included:

Rapid re-housing, which moved people into hotel rooms or other temporary measures.

Homelessness prevention programs, which helped people with eviction prevention or at imminent risk of losing their home and transitional housing.

Supportive housing projects, which help with the costs of running projects similar to the newly opened Bishop Skylstad Commons apartments in Pasco.

Who’s at risk?

Benton County Human Services Manager Kyle Sullivan said that early in the pandemic one of the biggest challenges they faced was the lack of rental units in Tri-Cities, where vacancy rates were near 1%, but now the main barrier is rising cost of rent.

“We had received COVID related dollars to get people off the streets to help prevent the spread of COVID, and it was not always easy, but people were able to transition into permanent housing,” he said. “I think the problem we’re seeing now is rents are too high, there’s that disparity between the amount of income someone has to spend for housing.”

The average rent for a 1-bedroom apartment in the Tri-Cities area has nearly doubled over the past 10 years.

It’s gone from $630 a month in spring 2013 to $1,175 by the first quarter of 2023, according to the University of Washington Center for Real Estate Research.

LoAnn Ayers, president of United Way of Benton and Franklin Counties, said there are a few groups that are now at particularly high risk of losing their homes or places to stay.

The largest group, Ayers told the Herald, is seniors who can’t keep up with rising rent costs on their fixed income, or have fallen behind because of mounting repair costs on their homes.

People fleeing domestic violence also are at higher risk of experiencing homelessness with the loss of expanded emergency housing funding and a tight rental market, where landlords can use legal means such as credit scores and income thresholds to be pickier about who they rent to.

Also vulnerable are young adults aging out of the foster care system.

While the state helps them with rent for a year after, most aren’t going to be making enough at age 19 to continue to afford an apartment in the Tri-Cities.

Ayers said these young adults also are at higher risk of falling into trafficking because they’re struggling financially.

Homelessness report cards

Last year, the Department of Commerce tracked 1,521 people in Benton County and 96 in Franklin County who entered programs designed to lift people out of homelessness.

The data shows that while homelessness prevention and other programs designed to help people get off the streets have had a big impact in the Tri-Cities, it’s taking longer to find them places to stay because of the tight housing market.

That means someone who isn’t able to get into a prevention program could be looking at months on the street before they’re able to get approved for help, according to the Homeless System Performance County Report Cards.

What the state counts as emergency shelters are programs such as temporarily housing through vouchers or, in other areas, publicly run shelters.

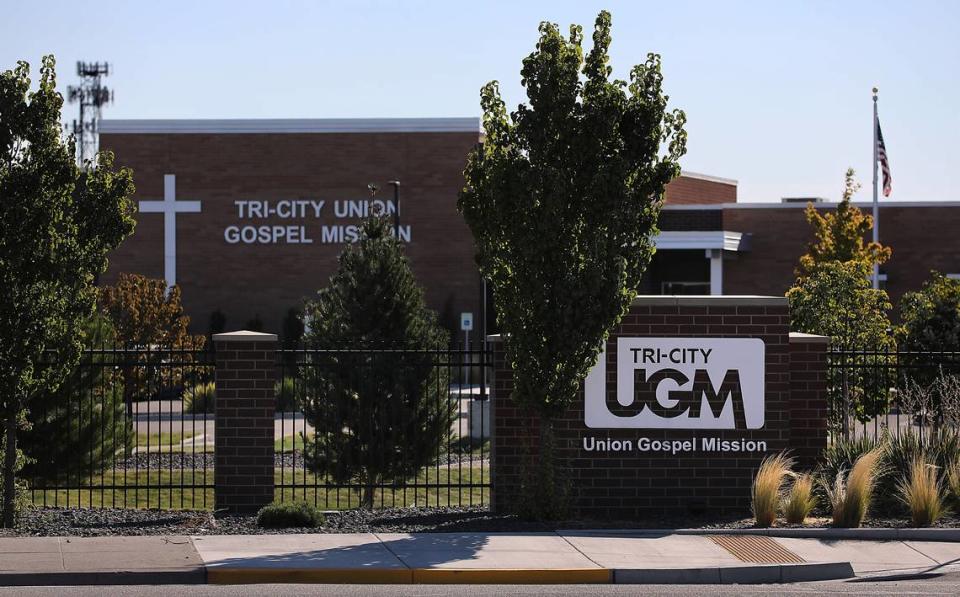

The Tri-Cities only has two homeless shelters, Tri-City Union Gospel Mission’s men’s shelter and their women and children’s shelter.

The Gospel Mission is a privately run nonprofit shelter funded through donations, so data from the state doesn’t account for much of the outcomes involving their services since the information is based on publicly funded programs.

Andrew Porter, the mission’s executive director, told the Herald that they’re already seeing an increase in demand for services. He estimated their requests for housing is up more than 20% this year.

What the numbers show

In Benton County the median length of time that people were homeless was 112 days, based on those who were being tracked.

That’s nearly three months longer than the median length of time in 2015. The department uses medians to remove outliers and produce more reliable information.

However, the number of people successfully leaving the programs into permanent housing is up more than 10%, with 69% successfully exiting in 2022.

Only 8% returned to homelessness within two years.

People in the Tri-Cities area typically wait about two months before applying, according to the data. Then it takes another month to get them into the requested services.

Parents are waiting even longer, with placements taking more than two months.

Nearly half of the people tracked in Benton County were living in a place not meant for habitation, fleeing violence or a had a history of either.

Those fleeing violence include people escaping domestic violence, sexual assault, stalking or other dangerous actions toward a member of the household.

Of the 1,521 people tracked in Benton County:

679 were in emergency shelters

540 entered rapid re-housing programs

260 entered homelessness prevention programs

About 40 were in permanent supportive housing or transitional housing

Those in rapid re-housing programs were the most likely to find success with 92% moving on to permanent housing.

The success rate for shelters was 42%, and it was 47% for transitional housing.

In Franklin County, only 96 people were tracked in 2022. That’s down from a peak of 1,174 in 2016.

Long-term shelter options through the Union Gospel Mission help account for some of this drop, with their new men’s shelter opening and the old one being repurposed as a shelter for women and children.

Many of the people who might have been otherwise had to rely on publicly funded services are receiving help through the nonprofit.

But Porter said it’s really the housing programs that have helped reduce homelessness numbers over the past decade.

He told the Herald that the decline started after a surge in homelessness in 2011-12, which prompted action from local elected officials.

Some residents only stay a few days at the shelter, but they have the option to stay for up to three months, while others who enter case management and social services programs can stay for up to two years.

That also means the people tracked as completely unsheltered in Franklin County are those with greater needs.

It’s important to note that not everyone program is ideal for each person applying. Some people have greater needs for wraparound services that help with issues such as mental healthcare, addiction and education.

“I think the problem comes in where we end up in situations where someone is chronically homeless. They’re on the street. They have no income. Trying to find a place for that person can be difficult,” Sullivan said.

Sullivan said that often means the person is likely to have a disability that interferes with their ability to find stable housing.

Preventing long-term homelessness

The length of time these people have remained homeless in Franklin County has grown from 39 days in 2016 to a peak of 340 days in 2021.

That number dropped to 298 days last year.

The good news is that 80% of those who entered the programs in Franklin County successfully exited to permanent housing, and only 13% returned to homelessness.

Porter said that wraparound services are critical for people who have experienced long-term homelessness.

He believes that the proposed bi-county recovery center will go a long way in helping people dealing with addiction or mental illness. Renovation work for the new facility is expected to start soon.

Participants successfully moving to permanent housing in Franklin County have steadily improved from 58% in 2016.

Those in rapid rehousing also were more likely to succeed in Franklin County, with 80% successfully moving into permanent housing in 2022. Only 20% of people tracked in emergency shelter did.

On average, programs in the Tri-Cities were statistically more successful than those in any other county in Washington with more than 100,000 people.

For example, Yakima county had 2,632 entries with 1,794 in shelters. and only 235 in homeless prevention programs. Their exits to permanent housing were at 19% last year.

At 8% of participants returning to homelessness, Benton tied with Whatcom County for the most successful large counties, and Franklin’s 13% was tied with Clark County for the second lowest numbers.

Sullivan said that a large part of Benton County’s success is due to his team’s relationship with the landlords involved in the program. With many, they’re able to work with the tenant and the landlord first to avoid evictions.

“I think some of it is the landlords we’ve worked with when we refer somebody,” he said. “It can be difficult because when you’ve got someone who’s chronically homeless, there’s a lot of things that impact that, when you get stable housing they can struggle sometimes.”

Sullivan said that in addition to the obvious challenges in escaping homelessness, such as mental health concerns or addiction, many people have feelings of guilt and try to help others they met while unhoused, leading to problems with their rental agreements.

Across the state, rapid rehousing is the most successful of the programs with 83% of people moving to permanent housing.

Only 17% of people living in shelters successfully moved to permanent housing in 2022, with more than 1 in 5 shelter residents returning to homelessness.

Meaning the longer it takes for someone to get help, the less likely they are to successfully move back into permanent housing.

Ayers said that the Tri-Cities has the ability to solve these problems, but it’s going to take everyone coming together and doing their part.

“It comes down to, as a caring community, watching out for each other. If you have a fragile family in your neighborhood or a senior who is struggling, how can you help?” Ayers said.

“The government wont solve everything, nonprofits won’t solve everything. But together we can do a lot.”