How will Tri-Cities hunger agencies manage the growing need as federal funds dry up?

More than half of the people in Benton and Franklin County surveyed said they’re struggling with affording enough to eat.

With COVID-19 related federal food aid ending, one might expect that food insecurity is down, but the need is actually growing in Tri-Cities area and Eastern Washington as a whole.

Organizations dedicated to fighting hunger told the Herald that there are more people in need and less food and funding to feed them with.

It’s a difficult position for both the people who need aid and the organizations that provide it.

Inflation and economic turmoil continues to drive more people to need assistance with basic needs, at a time when food banks are more dependent on cash than ever before.

Hunger’s ‘perfect storm.’ Cuts in funding leave food banks scrambling to feed Tri-Citians

“Ends don’t meet anymore for many, many families, so the lines are increasing in size,” Tri-Cities Food Bank Chairman Howard Rickert said. “The food banks have to change and basically work with less, buy more and distribute an increasing amount of food.”

Growing need

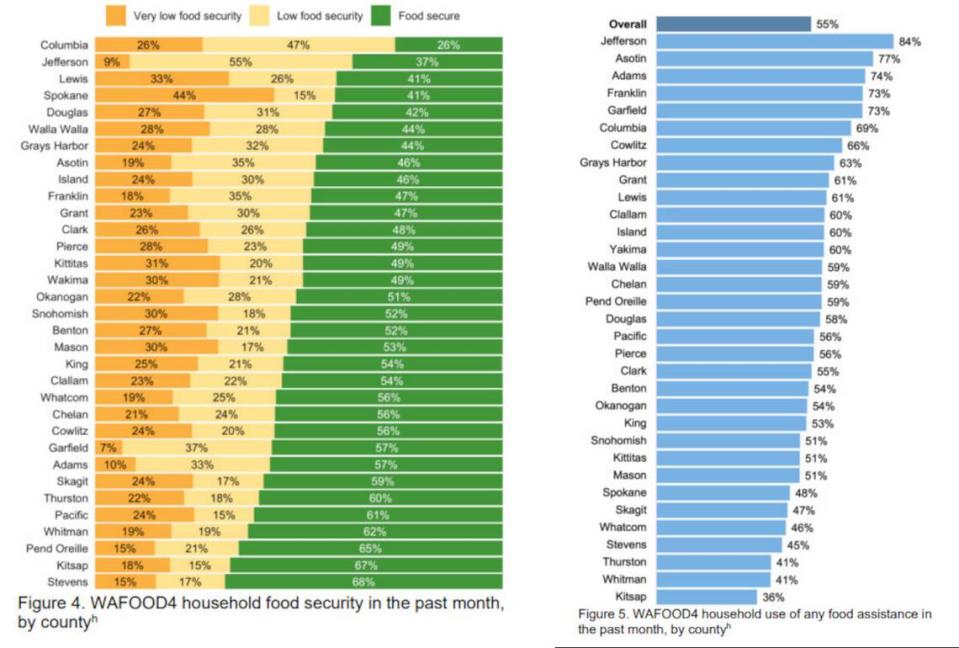

In a new Food Security Survey last December and January, 53% of Franklin County residents and 48% of Benton County residents who responded were considered food insecure.

After a year of lawmakers touting “economic recovery” aggressive inflation may have erased many of the gains families were making coming out of the first two years of the pandemic.

More than 1 in 4 Benton county respondents, and a little more than 1 in 6 of those in Franklin County fell under the “very low” food security category.

The percent of Benton County respondents considered food secure dropped by 15 points since the last survey, which ran through 2020 and 2021. In Spokane the drop was more than 21 points.

Franklin County did not have enough people participating to rank on that survey.

The survey is part of an ongoing, joint effort of the University of Washington and Washington State University.

The surveys over-sample lower-income households in order to get a fuller scope of the picture from the people impacted most, according to a report from the Seattle Times.

From 2015 to 2020 the official food insecurity rate in Benton and Franklin counties was about 10%, with an estimated average cost of $16 million total annually to make up that gap.

That number is based on data from Feeding America, which is the national parent network for regional food banks like Second Harvest.

The USDA defines low food security as respondents reporting “reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet. Little or no indication of reduced food intake” and very low food security as reporting “multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake.”

Shrinking aid

While it is unlikely that the official rate of food insecure residents in the Tri-Cities area has jumped exponentially, the survey helps explain increased demand being seen by hunger organizations across the region, as increased pandemic aid for food disappears.

Recent changes in federal funding will have the most immediate impact on SNAP recipients.

The emergency allotment program ended with February disbursements, meaning families on SNAP will receive $95 less per person this month, which is estimated to average $170 per household.

About half a million households in the state receive SNAP benefits. Seniors will be most impacted as they received larger than average increases in assistance.

Less SNAP funding could hit the Tri-Cities area particularly hard, with Franklin County having the most households saying they receive some form of food assistance of any county with a population of more than 35,000, and ranked fourth out of all counties of any size.

Three out of four Franklin county respondents received assistance from SNAP, WIC, free or reduced school lunches, help from food pantries or other programs. In Benton County, the rate of respondents receiving some kind of assistance was 54%.

Second Harvest Community Partnerships Director Eric Williams said Franklin County’s rate of households receiving help is probably due in part to effective community outreach.

The New York Times looked at four out of the 18 states that revoked the SNAP increases in 2021, and found that in Idaho, Arkansas and Florida food insecurity rates had risen by more than 5% in each state by the same time in 2022. In Nebraska food insecurity rates spiked like the other states, but leveled out by the end of the 12-month period.

Seniors and disabled people are at the highest risk of food insecurity, while simultaneously facing challenges with access to food and support.

Many seniors retired during the pandemic and many disabled or high risk individuals are still unable to return to work.

Despite the pandemic funding ending, and emergency declarations expiring, continued COVID surges still have a significant impact on immunocomprised people.

Most recently Benton County reported four COVID-related deaths for the week ending March 9, and community transmission level is considered substantial for healthcare facilities.

That means high-risk people who can’t drive face greater challenges with access to food banks, having to use public transportation if they cannot get deliveries and having to brave grocery stores at a time when most COVID-19 precautions have been relaxed.

Meanwhile inflation continues to rise. After an almost 7% increase last year, inflation began to slow. However, the Seattle metro area saw an increase as the new year began.

The Department of Labor’s Consumer Price Index showed that inflation going into February in the Sea-Tac area was up 8.4% over 2021, according to Patch.com. Data was not available for the rest of the state.

Nationally, food prices rose by about 10% from Feb. 2022 to Feb. 2023, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Of the Washington residents involved in the food insecurity survey, 83% said they had noticed the cost of groceries going up, 80% were worried about price increases continuing over the next six months.

“(Last) week I talked to a pantry organizer who said their number of clients is up 20%, another said they were up 30%,” Williams said.

Williams said some areas are seeing spikes in demand by as much as 100%.

Increase in other costs from February 2022 to last month, according to the BLS:

Electricity - 12.9%

Natural gas - 14.3%

Shelter - 8.1%

Transportation services - 14.6%

How to help

Williams said that while funding sources are down, donations continue to be in line with pre-pandemic levels.

“The monetary side is about at, or slightly better than prepandemic,” he said. “The food donations are down, no reduction in generosity, but in supply. We are so fortunate to be in an area that is so bountiful and the producers and processors and grocers are all so generous.”

He stressed that any help individuals, organizations, farmers or grocers can offer makes a difference.

“We’re often asked, which is a better donation (food or money)?” Williams said. “Today the answer continues to be ‘Yes.’ Whether it’s food or money.”

This month Second Harvest is celebrating its agricultural partners with a fundraising drive that will see up to $15,000 matched by AgWest Farm Credit and Northwest Agricultural Consultants.

Second Harvest also received a donation of 73,000 pounds of potatoes from a local producer last week.

“We’re just so appreciative of the people who work in the fields and do everything they can to feed us all,” Williams said. “We’re very keen to the fact that it’s first the farmers that make the Second Harvest possible. “

Some families and individuals may also be eligible for up to $1,200 in state tax credit in the form of a cash payment, through the Washington Working Families Tax Credit.

The credit is available through Dec. 31, 2023 and is open to Washington families with children in the household or meeting income requirements. Amounts range from $50 to $1,200 depending on eligibility.