Trial by pandemic: In their initiation as doctors, they face the worst health care crisis in a century

This story was republished on Jan. 5, 2022 to make it free for all readers

In her first year as a doctor, Kim Tyler learned what it felt like to look into the frightened eyes of a COVID-19 patient, a young man who’d been advised to get his affairs in order, and now had a question.

"Am I going to die?"

In 2020, Kim discovered that being a doctor at Froedtert Hospital during the worst pandemic in a century meant answering the question as best she could. On other occasions, it meant staring at the phone before calling relatives of a dying patient, wondering: “How am I going to say this in a way that makes sense, that’s kindly, but doesn’t sugarcoat it?”

In his first year as a doctor, Kim’s classmate from the Medical College of Wisconsin, Marc Drake, learned to push past the moment of doubt when he would enter a patient’s room and freeze. Decisions that had once felt as abstract as the pages in a textbook became as real as the patient’s voice calling him “doctor,” and the trust implicit in the title.

“You think, ‘I’m about to set us on a course that will have major consequences for this person. I am an agent now,’ ” he said. “I’m more of a pensive person and surgeons are typically doers. That’s something I’ve had to get used to: being the doer, the first person to act.”

Facing the pandemic in his first year, their classmate Jamie Jasti wrestled with the paradox of trying to calm scared patients from behind a mask and layers of protective equipment. A married father of two with a third on the way, Jamie learned to reassure patients by slowing his voice, looking into their eyes and controlling the parts of his face that were visible outside the mask.

Through four years at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Kim, Marc and Jamie had been classmates and friends. Kim and Marc co-edited the college’s literary journal. Marc and Jamie met for monthly jam sessions, Marc on guitar, Jamie, piano.

All three began their medical careers at the college’s affiliated hospitals, including Froedtert and Children’s Wisconsin.

They were among the 34,000 first-year residents across the U.S. who took their first steps as doctors straight into the middle of a pandemic.

They endured an initiation into medicine like no other.

“It was worse than hazing,” said Jessica Gold, a psychiatrist who sees health care workers and also teaches in the psychiatry department at Washington University in St. Louis. “If hazing is what residency has always been, this was like hazing with death and pain and fatigue and sleepless nights for a year straight without having time to process it.

“It’s not normal to see that many people die, but you’re not supposed to say that out loud.”

Their experiences and those of others working in the nation’s hospitals forced a reckoning that has been long overdue. Even before COVID-19, medical doctors had the highest suicide rate of any profession in America.

“Physician mental health has been the elephant in the room for as long as medicine has existed,” said Mona Masood, a psychiatrist who treats doctors near Philadelphia. “It’s the thing nobody wants to talk about.”

Looking back on 2020, Marc said, “My career as a physician will forever be defined by this time. The only time that I know how to be a doctor is in the time of COVID.”

Match Day

Across the nation, residency begins with the traditional celebration known as “Match Day,” when graduating medical students are called to the front of an auditorium, one by one, like NBA draft picks.

It’s at this moment that they learn the hospitals where they will spend their first, formative years as doctors. Most residencies last between three and seven years, depending on what specialty the doctor chooses.

In March 2020, Kim, Marc, Jamie and their classmates were to celebrate Match Day at the Italian Community Center in Milwaukee’s Historic Third Ward. It would be a large, boisterous sendoff: almost 300 whooping and hollering graduates, plus families, spouses and faculty members ― all focused on a barrel up front filled with envelopes.

On the outside of each envelope would be the name of a different graduate; on the inside, a computer-generated letter identifying the graduate’s new employer.

After receiving the letter, each graduate would leave a dollar in the barrel. The final recipient would take home the cash, or put it toward a party for the class.

That was the plan. Then came COVID-19.

On March 20, a very different version of Match Day arrived for Kim, Marc, Jamie and their fellow graduates. With the big celebration canceled, new residents waited to learn their hospital assignments at home.

By then the potential scope of COVID-19 was just coming into view. Total cases in the U.S. had reached 23,640 including 273 deaths; Wisconsin’s totals stood at 251 cases with four deaths.

“Things were changing by the hour,” recalled Marc, then 27. “COVID was ramping up in earnest. I was at my house with my fiancee. We got the email at 9:56 a.m.”

Marc and his fiancee, Kelsey, celebrated with Champagne and a big tiramisu from Whole Foods. “I’m not sure what we toasted,” he said. “It was like a blur.”

The two had planned to marry in another month, on April 24, then spend their honeymoon backpacking through Newfoundland. COVID-19 forced them to postpone the wedding. Not until Oct. 4, 2020, would they marry in a smaller-than-planned ceremony for immediate family.

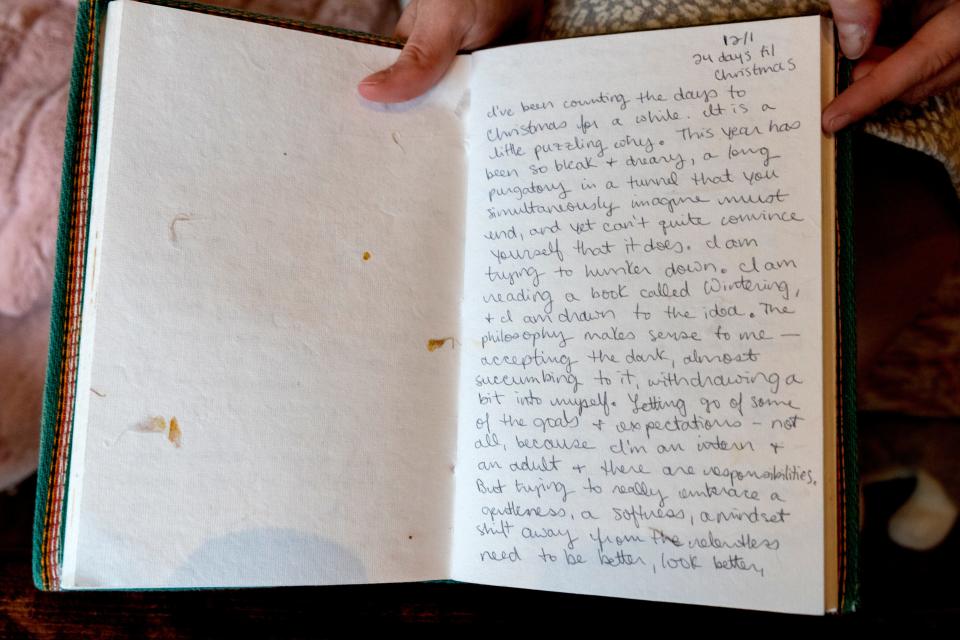

For Kim, then 29, the uncertainty of where she would spend her residency was maddening. A writer of “to-do” lists, Kim kept paper beside her bed in order to update tomorrow’s tasks. Writing offered a sense of control.

When she realized early in the pandemic that her medical career was beginning at a historic moment, Kim started a journal.

On Match Day, she and two of her closest friends from medical school ate breakfast together, glancing at their phones for the emails announcing the hospitals they would join.

When the friends received word, their response was low key. No Champagne. They spent the rest of the day just hanging out together.

For Jamie, the day carried a sense of urgency and destiny.

He had been watching the early images of COVID-19 overwhelming hospitals in New York, trying to imagine what it would be like to work under such pressure.

“At the same time that I was anxious and scared,” he said, “I was in awe of how our specialty responded to help patients who were clearly very sick.”

At 31, Jamie had spent the better part of his life preparing to care for the sick. His extended family includes six doctors.

Growing up, he would hear them talk about their work. “I couldn’t help but think what it would be like for me as a physician,” he said.

College research projects took him to the trauma bay at Froedtert Hospital, where he watched in wonder those extraordinary moments when medical staff restore life to the dead.

When word of his hospital assignment arrived, he was at home with his wife, Sarah, and two children: Jude, 4, and Ari, 2. The family celebrated with mimosas (for the grownups) and homemade cinnamon buns.

Jamie would begin his career in a familiar place. They all would. Kim, Marc and Jamie would be staying together, working for the Medical College's affiliated hospitals.

This was welcome news. The Milwaukee area felt like home to Marc and his fiancee, as it did to Jamie and his family.

Kim too had made friends in the city, which was a modest five-hour drive from her family in Indianapolis.

Traditions vanish

The scaled-back Match Day was only the first indication of what was to come. The new coronavirus would rewrite much of the residency experience.

Gone were the traditional group discussions of cases and treatments known as “grand rounds.” Gone, too, were the opportunities to spend 15 minutes in the cafeteria unburdening yourself to a colleague after a gut-wrenching experience or a period of high stress.

Social distancing rules barred medical staff from sitting together in the cafeteria or even meeting for group sessions in someone’s home.

Death itself ― the essential fact all new doctors must face ― seemed especially harsh and alien in the COVID-19 wards. Patients declined rapidly, surrounded by machines and often silenced by breathing tubes that made it impossible for them to talk to medical staff.

Visitor restrictions aimed at slowing the pandemic meant that dying patients were unable to depart surrounded by loved ones. If they were well enough to talk, people uttered last words to a single relative in person, and to the rest over cellphones and tablets held up to their faces by medical staff.

Other patients had already lost consciousness by the time health care workers placed the tablet in front of them. Sons and daughters were left to wonder whether Mom or Dad had heard their voices at all.

Virtual orientation

In New York and other early pandemic hot spots, medical residents had no time to prepare for such scenes. They went from graduation to the front lines in a matter of days.

In Wisconsin, where the real flood of patients would come months later, residents had the luxury of an orientation, though it bore little resemblance to those in years past.

“Good morning, everyone.”

Kenneth Simons, senior associate dean for graduate medical education and accreditation at the Medical College, greeted the 305 incoming residents and fellows by webcam from a near-empty lecture hall.

It was June 30, a day when Wisconsin would record 533 new COVID-19 cases and two deaths.

“It feels really strange to be saying ‘Good morning’ to a room for 250, 300 people with two people in it right now,” continued Simons, who oversees the Medical College’s residency programs.

In orientations past, the residents would have toured Froedtert Hospital and Children’s Wisconsin. They would have learned the locations of the different departments, the cafeteria and the call rooms, where night shift residents try to steal a few minutes of sleep before their pagers buzz.

In 2020, orientation was entirely virtual.

On the screen, Simons clicked to a ghostly illustration of a young boy delicately navigating a thin wire stretched out into the night sky.

“That kind of feels like me,” he told the group. “I feel like one misstep and I’m falling off the cliff.”

In his role overseeing residency, Simons faced hard decisions with potentially severe consequences.

Given the shortages of personal protective equipment, he was under pressure from some to conserve supplies for veteran staff and provide what he regarded as inadequate protection to the residents. He refused.

Already, residents were concerned about the possibility of bringing the virus home to their families. He made sure they could stay at local hotels paid for by their hospital, a benefit that was being provided to the other medical staff.

Mistakes could lead to outbreaks among patients, staff and their families. And then there was the psychological toll the pandemic would take on these young doctors. Much of the nation had heard the story of Lorna Breen, a strong, confident woman who had supervised the emergency department at New York-Presbyterian Allen Hospital in Upper Manhattan. Feeling exhausted and overwhelmed by the pandemic, Breen had taken her own life in late April.

Simons could not help but think of a 2017 study of more than 380,000 residents that had found suicide to be the second leading cause of death among the entire group, and the leading cause among male residents.

He did not mention the study in his remarks. But Simons urged new residents to have no hesitation in seeking counseling, to remember their careers were beginning at a time with no parallel in recent memory.

“These are changes no one has faced in a hundred years,” he said.

The concept of residency

The modern concept of residency dates back to the 1890s and William Osler, one of four founding professors of Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

The program Osler envisioned would usher young doctors into the art of healing, moving them from the lecture hall to the hospital, from observing a professor to treating a patient.

“In what may be called the natural method of teaching,” Osler wrote, “the student begins with the patient, continues with the patient and ends his studies with the patient, using books and lectures as tools, as means to an end.”

In an 1889 speech to students, Osler described the essential qualities they would need. A doctor must show “calmness amid storm, clearness of judgment in moments of grave peril,” and never betray indecision or worry, which “loses rapidly the confidence of his patients.”

Osler cautioned that doctors must control their emotions, “without at the same time, hardening ‘the human heart by which we live.’ ”

The balancing act he described more than a century ago was never more vital to medical residents than in 2020.

First day

Nightmares haunted Kim even before residency began. In one, she forgot to perform physical exams on every one of her patients.

On her first day, July 1, she focused on the basics: not getting lost in the hospital, finding her workroom and remembering the passcode required to enter.

Arriving at Froedtert Hospital that day, Jamie felt his stomach swirling. His mind raced, alternating between disbelief, excitement and self-doubt. He could not wait to begin taking care of patients. Yet he wondered: Am I ready? He wondered, too, how he would balance his responsibilities at the hospital with those at home.

After years of being trained to think like a doctor, Marc discovered on his first day that a medical mindset doesn’t cover all the basic questions. New ones kept popping up. How do you set the proper dose for medications? How do you admit a patient into the hospital?

These would become second nature soon.

COVID-19 would not.

No road map

The pandemic was new to the residents, but also to the doctors to whom they looked for guidance. In years past, residents arrived at their hospitals nervous but reassured by the presence of a veteran medical staff that could guide them through any situation.

The day Kim, Jamie and Marc began their medical careers, Wisconsin recorded 519 cases of COVID-19 and four deaths from the disease. Were those numbers high? How much higher would they go? No one knew.

Doctors and scientists across the globe were still scrambling to learn how the new coronavirus caused such damage and produced such a wide array of symptoms ― fever, coughing, shortness of breath, loss of smell and taste, even the red swelling known as "COVID toes." When it came to treating the disease, medical staff had little to go on.

“Everyone was kind of doing this for the first time,” Marc said. “There was no road map to direct me.”

Doctors had found that laying oxygen-deprived patients on their abdomens helped. As for medications, by July, the antiviral remdesivir was the lone treatment to have received “emergency use authorization” from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, a step below full approval.

Beyond that one drug lay confusion.

President Donald Trump continued to promote the anti-malarial medication hydroxychloroquine, while the scientific community sent mixed signals. Many said there was no evidence the drug helped COVID-19 patients. One journal, The Lancet, went further, publishing a study in May suggesting use of hydroxychloroquine on COVID-19 patients increased their risk of death. Two weeks later, the journal retracted the study.

A separate paper on July 2 in The International Journal of Infectious Diseases suggested that COVID-19 patients who received a small dose of hydroxychloroquine within the first two days of hospitalization were more likely to survive. Almost immediately, other scientists attacked the study, citing flaws.

In August, the FDA announced another treatment option, granting emergency use authorization for plasma from recovered COVID-19 patients.

The uncertainty on treatments and countermeasures filtered down from the scientists, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the FDA, to the doctors and finally to the patients and the rest of the public.

"I had family members ask about CDC guidelines," Marc said. "You felt like you were summarizing a moving target."

'Am I ready to be here?'

Kim was the first of the three residents to treat a COVID-19 patient.

He was younger than she’d expected and otherwise healthy. She remembers looking at him and thinking: He’ll be fine. And he was. He recovered quickly and was discharged from the hospital.

The happy ending did not prepare her for what was to come.

Long shifts at the hospital spilled over into her dreams. “In July,” she said, “a lot of the dreams that I had directly related back to this one question: Am I ready to be here?”

That month, Wisconsin’s daily COVID-19 cases more than doubled, reaching 1,117 with six deaths on July 31.

At the end of her first month of residency, Kim wrote a short essay.

“The first time I was summoned to pronounce a patient’s time of death, I stared at my pager wondering if they’d contacted the wrong person,” she wrote.

“As I move through my days, I experience twinges of incompetence. I fear that a patient might call me out. Of course, this is a familiar theme for many during the pandemic. None of us has the faintest idea where this is headed, and uncertainty lingers over all of health care.”

Residents constantly faced the vastness of what they did not know. But Kim suspected that this was a time when the entire medical community was in the dark and needed to be honest about it.

“Do even the most confident attending (physicians) have moments of distress?” she wondered in her essay. “Is there, in this moment, an opportunity for all of us to acknowledge our hidden feelings of inadequacy and hesitation?”

Imposter syndrome

Marc, too, struggled with hesitation and self-doubt.

In the hospital hallways and patient rooms, residents learn a delicate balancing act central to the practice of medicine, the need to be both planner and doer. Calm and considered but also quick and decisive.

Physicians, Marc explained, perform an operation three times: the first as they walk to surgery, thinking ahead and running through each step; the second during the actual procedure; and the third, afterward when they replay what happened.

Before becoming a resident, Marc had never felt the full weight of that process.

“As a medical student,” he explained, “you live in this abstract place where you can think about the plan and then present the plan. But now you have to be the one who carries it out.”

Now, patients would lean over to check his identification badge and jot down his name. Other doctors watched him. He was always aware that his work could wind up being critiqued at one of the weekly or monthly in-hospital conferences.

In this new role as Dr. Drake, Marc recalled that he would walk into a patient’s room thinking: OK. Game time. Then his pensive nature would kick in. He would freeze for just a moment.

He would take a deep breath, acknowledge the situation in the room, and remind himself: I do belong here.

The hesitation offered a window into a larger phenomenon experienced by many new workers, but especially doctors: Imposter Syndrome. The syndrome was first identified in 1978 by psychologists examining high-achieving women.

“Women who experience the imposter phenomenon maintain a strong belief that they are not intelligent; in fact, they have fooled anyone who thinks otherwise,” wrote the authors, Pauline Rose Clance and Suzanne Ament Imes, in the journal Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice.

Although the fear of being exposed as a fraud can affect any new employee, it is especially acute in medicine where the stakes are quite literally life and death.

A 2016 study of 138 American medical students found symptoms of imposter syndrome in 49% of female students and 24% of male students. A 2008 study that focused exclusively on medical residents in a Canadian hospital found feelings of imposterism in almost 44%.

“There will be a first day that you run a code (for a medical emergency). There will be the first day that you lose a patient. There will be a first day for a lot of things,” said Masood, the psychiatrist who treats doctors near Philadelphia.

Moreover, since residents make the rounds of all patients on a floor, they’re in a better position to break away quickly and respond to an emergency. The more experienced attending physicians tend to spend more time with individuals and may be in the midst of discussions they cannot abandon in an instant.

Often it is the residents who arrive first.

Seeing red flags

In 2020, especially in the early months of the pandemic, it was all too easy to feel like an imposter — not only for residents but for doctors with many years of experience.

“We don’t have a treatment algorithm. We just don’t know what we’re doing, and anything we’re doing isn’t working,” said Michael F. Myers, summarizing comments he heard from doctors early on at a support group at the State University of New York Downstate in Brooklyn. Myers wrote the book, “Becoming A Doctors’ Doctor: A Memoir,” about his 35 years as a psychiatrist specializing in the treatment of physicians.

As Myers was hearing desperation in his small support group, Masood was reading troubling posts in a Facebook group frequented by thousands of health care professionals. Doctors felt exhausted and overwhelmed by the mass of extremely ill and dying patients.

One post, in particular, lodged in Masood’s memory:

"Does anyone know a good lawyer to write a will?

“It became a red flag,” Masood said.

She responded quickly, putting out a call for all psychiatrists willing to counsel doctors for a new Physician Support Line. Almost immediately, 50 volunteered. Then 100. In the first two days, 200 psychiatrists signed up.

A year later, more than 800 psychiatrists across the nation staff a telephone support line that has surpassed 3,000 calls.

“Everyone is looking to the doctors to have the answer to this thing,” Masood said. “In some ways, the expectations of the nation were put on this group of people who’d never seen this before either.”

Residents phoning the support line described their fear of catching the virus in their hospitals. Masood recalled one common refrain: “We’re the ones seeing the patients. It often feels like we’re the sacrificial lambs.”

Facing the virus

In August, Marc carried out his first tracheotomy on a COVID-19 patient.

The surgery opens a direct path through the neck and into the airway so that doctors can insert a breathing tube.

Marc knew that many of those infected with the virus were undergoing tracheotomies, and he knew the procedure put doctors at especially high risk of becoming infected. Scientists had determined that COVID-19 spread through droplets, some as fine as mist or aerosol.

Marc performed the tracheotomy not knowing whether his patient had COVID-19.

“You’re there, centimeters from their lungs looking into the opening where the breathing tube gets placed,” Marc said. “You have all of your Personal Protective Equipment on, but your mind starts to spiral. Did I put on my PPE correctly? Did I pinch the nose of the mask correctly? Are my glasses falling off my face?”

Soon after the procedure, Marc learned the patient had tested positive for COVID-19. The man became a vivid reminder of what was at stake each day.

After the surgery, Marc cared for him for another two months, but the patient remained in the hospital for twice as long. In the end, doctors could not save him.

“I can picture his face clear as day,” Marc would say a year later.

Focusing on the patients

Hospital staff trained extensively, following detailed instructions for donning and removing protective suits, gloves and masks.

During practice runs, the equipment was laced with dye only visible under ultraviolet light. “If we’d gotten any of the dye on us, we’d compromised ourselves,” Jamie said.

Outside the room of every COVID-19 patient, the hospital posted laminated cards detailing safety procedures. Jamie didn’t need the cards. He had committed the checklist to memory.

Steps included rubbing hand sanitizer over the gloves to kill any molecules of virus that might have come from the patient. Doctors were told to remove their gowns and roll them away from their own bodies. Gowns went straight into the trash.

“You’re seeing some really sick patients with weakened immune systems,” Jamie said. “You think about how easy it is to transmit this infection. You’re constantly reflecting on the impact and consequences if you aren’t doing it right, if you’re not wearing a mask properly.”

Jamie learned to work around the barrier that the protective equipment placed between himself and his patients.

He understood the necessity. Every day, doctors were questioning their own coughs. Is it seasonal? Dryness in the throat? Or the virus?

Jamie made sure to sit beside the patient’s bed. He never wanted to be looking down on the patient, a posture that might add to their feeling of powerlessness.

Even though his face was covered by a mask, he controlled the muscles. He composed himself so that if he felt stress or fatigue, it would not show. He would ignore the bustle of the hospital.

All that mattered was the patient in front of him.

“You have to learn to over-emphasize the use of your eyebrows or your voice intonation to convey information,” he said. “You want to be able to demonstrate good news.”

When he spoke, he avoided medical jargon. He kept his voice soft and reassuring. He spoke slowly, pausing to allow each new piece of information to sink in.

Projecting calm was crucial when treating the most severely ill COVID-19 patients, those struggling to breathe.

“In their eyes you see fear, anxiety,” Jamie said. “That sensation that you cannot breathe ― there are other life-threatening conditions, but I think your ability to breathe is probably the most psychologically provoking to the body. It’s such a tangible thing. You see the patients, they’re terrified and it gives us anxiety, too.”

He felt it essential to hide any anxiety. “I’m calming,” he said, “and trying to give them hope.”

'Bleed and bleed and bleed'

In Wisconsin, the deluge of pandemic patients came in November, and it made the worst days of July seem tame.

In the first month of residency, new COVID-19 cases never reached 1,200 in a day; deaths never topped 12.

On Nov. 2, the state recorded 5,596 new cases and 52 additional deaths.

There were so many COVID-19 patients that Froedtert was forced to move people hospitalized with other ailments to make room.

Small conference rooms that could barely fit a hospital bed suddenly were converted so that each one could house one non-COVID patient. Other patients were moved into hallway areas that had been separated by curtains to create makeshift rooms.

On the COVID-19 ward, Marc confronted images the public seldom if ever saw.

“You didn’t hear as much about this in the media: These patients bleed and bleed and bleed,” he said. “We’d have doctors say: ‘They’re bleeding through their noses and their mouths. We can’t stop it.’ ”

The profuse bleeding some patients experienced was puzzling, especially since others with COVID-19 suffered from the reverse ― dangerous blood clots.

“It is quite uncommon, but not unheard of,” for a disease to cause both clotting and bleeding out, said Daniel Lawrence, a professor of basic research in cardiovascular medicine at the University of Michigan.

Why some patients bled so much remains unclear, Lawrence said. “I don’t think we really know the answer. We do know that the incidence seems to be much lower than it was in the beginning.”

Whatever the explanation, the symptom was so shocking and visceral that Marc could scarcely believe there were people outside the hospital insisting the pandemic was a hoax. Some even told him so after his shifts.

He wished the doubters could have seen what he saw.

“I had someone’s blood on my hands when they were bleeding out,” Marc said. “My word’s not good enough?”

Many of the patients were unconscious by the time he saw them. There were no visitors. The quiet in the rooms felt unfamiliar and unsettling.

“For me, one of the core aspects of medicine is narrative,” Marc said. “One of the first things we learn to do is get a story from the patient.”

Too often, however, the patients Marc saw looked like Snow White, locked in the deepest sleep, surrounded by a spaghetti-like network of tubes.

As they lay there unconscious, it was the photographs and other objects around the room that spoke to Marc, giving him a sense of who his patients were. Here was a wedding picture, a son or daughter’s graduation photo. Here was a photo of the patient in better days enjoying a concert. Marc would look at the photo and think, “I know that band.”

Familiarity made the fight against the virus even harder.

“When you look at them as a person and not a medical problem,” Marc said, “the weight of failure becomes more real.”

Kim spent November working on general in-patient medicine.

Her team was always caring for at least one COVID-19 patient. But not until a few months later when she worked in the intensive care unit did she see people fighting for their lives. For now, there were only hints.

“We had a really sweet elderly woman,” Kim recalled, “and I’d walk into her room and say, ‘It’s 85 degrees,’ and she’d say, ‘Oh, I’m cold.’ ”

Much of the time Kim would talk to the COVID-19 patients without entering their rooms, using the hospital phone beside the door to ask about their coughs, their breathing, their appetite.

Some patients told her their whole families were sick with the virus.

Chance meetings

From time to time, Kim, Marc and Jamie would cross paths in the hospital hallways, and chat briefly about how first-year was going.

Jamie even consulted Marc on patients with ear, nose and throat conditions ― Marc’s specialty.

“It’s always a nice surprise when I hear his voice at the other end of the phone,” Jamie said.

On some occasions, Kim would see Marc in the hospital, and her spirits would lift at the rare opportunity to catch up. Then she’d notice that he was with a supervisor, the chief resident or the attending doctor. The look on Marc’s face said: “Busy.”

In medical school, Marc recalled: “Kim was the person everyone would go to if they had a bad day. It’s impossible to be sad in a room with her.”

Now that they were residents, meetings were sudden, and sometimes awkward.

Once, Kim ran into Marc at the VA Medical Center and was so delighted to see him that, for just a moment, concerns about COVID-19 and social distancing vanished. She hugged him.

“I’m sorry," she texted later. "I didn’t ask if it was OK.”

Learning to relieve stress

Through 9- and 10-hour shifts, Jamie seldom had a moment to sit. After work, he would drive home, soreness radiating through his feet, ankles, calves.

In the garage, off came the scrubs and shoes. Then inside for a shower.

“Daddy!”

There was a music to the voices of his children, Jude, who was now 5, and Ari, now 3. Jude would run up and wrap Jamie in a hug and ask when his next shift would be.

In good weather, they would have a few hours left to play before nightfall. Jamie and the boys enjoyed tag, hide-and-seek, basketball and soccer. They took bicycle rides through the neighborhood. Sometimes they just played catch in the backyard.

Before bed, the boys listened as he read stories from the “What Should Danny Do?” series. The stories allowed them to choose what Danny would do; depending on the choices they made, the story would move in different directions.

At home with his children, the day’s stress lifted away, as if he’d hit a psychic reset button.

After the children went to bed, though, sometimes Jamie would stare off with a blank look. Sarah knew that look. He was brooding.

That patient who came in with abdominal pain: Did I discount a diagnosis too quickly?

Could I have managed her pain more effectively?

Was I communicating clearly with the nurses?

Sarah would get Jamie to talk and they’d unpack the problem together. She would keep him focused on the crucial difference between what he could control, and what he could not.

“I can’t put into words how important that was,” he said. “I can’t imagine going through it without her, without being able to confide and share the emotional isolation of the pandemic.”

The residents all coped in different ways.

On pleasant evenings, Marc and his wife would have dinner on the patio of their Brewer's Hill condo and look out on the Milwaukee River. When alone, Marc found it cathartic to write about his experiences. “I was trying to make a cohesive narrative of everything that happened this year,” he said.

Kim looked forward to time at home with her Chihuahua-pug mix, Remus, who was happily oblivious to the stress of the day, and just excited to see her. Sometimes she’d unwind by re-reading “Harry Potter” books.

After 28-hour shifts, she celebrated with sleep followed by Mexican takeout.

But it was jogging from her home in Walker’s Point toward the Brewers’ ballpark that took her furthest away from the sorrow and stress of the hospital.

“Running,” Kim said, “is a time when I forget the hospital even exists.”

Hope and fear

The winter holidays were approaching.

“I’ve been counting the days to Christmas for a while,” Kim wrote in her journal. “It is a little puzzling why. This year has been so bleak and dreary, a long purgatory in a tunnel that you simultaneously imagine must end, and yet you can’t quite convince yourself that it does.”

Kim continued: “The philosophy makes sense to me ― accepting the dark, almost succumbing to it, withdrawing a bit into myself ... trying to embrace a gentleness, a softness, a mindset shift away from the relentless need to be better, look better, sound smarter, inch my way to a perfection that does not exist.”

In early December, the U.S. approved the first vaccines against COVID-19, “so there was also a lot of hope against hope,” Kim said. “But you didn’t want to fully let yourself feel that way, because what if the vaccine turns out to be months away?”

Marc felt giddy. He had no doubt that the vaccines were coming.

“It felt very imminent,” he said, “like a Christmas gift.”

At the same time, public health experts predicted the holidays would trigger another surge in COVID-19 cases. Jamie’s relief that the vaccines had reached the finish line was tempered by the question: How bad are we going to get hit?

People were weary and fed up after the months of isolating inside, wearing masks, avoiding visits to grandma and grandpa, ordering food to go instead of sitting in restaurants, watching sports on television instead of tailgating outside the stadium.

For many, the simple phrase, “Home for the holidays,” became an anthem.

And a siren song.

What is a good death?

"Am I going to die?"

It was January and Kim looked at the patient who’d addressed her from his bed in the crowded intensive care unit. She collected her thoughts.

Her patient was part of the post-Christmas spike in COVID-19 cases that experts had feared. On Jan. 6, Wisconsin reported 3,760 new cases and 28 deaths. Christmas Day there’d been only 614 new cases and no deaths.

The man in bed looked in better health than most of the COVID-19 patients Kim had seen perish. Yet she had been wrong before. Patients she was sure would improve had weakened abruptly and died.

Kim had strong feelings about her obligation to answer the patient truthfully. When people are dying, and ask if they are dying, she said, “They deserve to hear someone say, ‘Yes.’ ”

She explained to the patient that he had a serious disease but was in other respects relatively healthy. He did not have the other conditions such as diabetes, heart disease and obesity that put people at greater risk of dying from COVID-19.

“Everything looks really good right now,” she recalls telling him. “We’re going to keep a really good eye on everything. We’re going to try to do the worrying for you. We’re going to be looking at every lab value and every heartbeat.”

“Lab values” are measurements that characterize a patient’s kidney function, electrolyte balance, blood counts and other important health indicators.

Kim’s patient endured a long hospital stay, but he survived.

"Am I going to die?"

Other patients asked. Each time, Kim had to consider her answer.

To one woman she said:

“I’m hopeful, but I’m really worried that things might not go well, and this is what it might look like. If that were to happen, Plan A is that you get better, but if we have to resort to Plan B, what would you want that to look like?”

At times, Kim returned to the question that had arisen years ago when she helped her grandmother navigate Alzheimer’s: What is a good death?

As it turned out, the female patient never had to ask; she survived, too.

Residents all saw patients who were afraid. They sought ways to acknowledge the fear, while easing it.

“I remember saying, ‘Look, we know this is scary,’ ” Jamie said. “ ‘You’ve got this disease you have heard about on the news, but we’ve already learned so much. You can be assured we’re going to apply the knowledge we’ve gained to help you.’ ”

Families say goodbye

Kim had another work-related dream. She was treating a patient she knew. Her grandmother.

“I wasn’t there when she died,” Kim said, “and that has always bothered me. But this was a nice kind of dream actually, because I was able to do what I wasn’t able to do in real life: be with her.”

Decades later, the first-year doctor found herself phoning families who faced a similar sorrow. Visiting rules limited the dying to one relative.

Kim hated having to tell family members that only one would be allowed into the hospital. Sometimes she wondered which was worse, the long-distance goodbyes by phone or the loneliness of a final in-person visit.

“You know you are going to see death and suffering and really difficult things,” she said of becoming a doctor, “but I’d never imagined there would be times I would say, ‘Yes, he’s dying, but only one person can come in to see him.’

“I would think about how hard that is. One person is driving themselves in and they have to say goodbye and then ― Oh, man ― they’re going to have to get themselves home.”

Surrounded by heartbreak, Kim resolved to be present for the families, whether in-person with a single relative or over the phone with the others.

On the phone, grief had a sound all its own: an awful wailing. She knew that it was different for her than for the relatives. Still, she said, the death of each patient hit “right in your gut.”

She would feel hot and flushed.

“There were days I did not have an appetite,” she said, “because I had to make some call and you’re just emotionally defeated.”

Kim would be professional in these talks, but she would do so without distancing herself.

She came to view the work as “learning how to climb into that hole with the family, and then learning how to climb out of the hole afterward.”

Talking with a therapist

Twice a year, the Medical College mails anonymous surveys to residents and medical students designed to identify depression and suicidal thoughts.

The surveys were intended to encourage self-health in an occupation that often breeds the opposite, said David Cipriano, the college’s director of student and resident behavioral health.

“In a normal year, it is a very taxing profession, and part of that culture of medicine is one of self-sacrifice,” Cipriano said. “ ‘I just have to keep giving and giving and giving.’

“It’s normal to feel depleted. It’s not acceptable to show weakness and vulnerability.”

The college recognized that 2020 was anything but a normal year and set up virtual support groups to allow the residents and medical students to share their experiences. Residents also were offered free therapy sessions.

Despite the residents’ grim pandemic duties, Cipriano was surprised to find that their levels of depression and suicidal thoughts “stayed pretty stable.” Also, the use of free therapy sessions was actually about 4% lower than normal. Cipriano said this may have been because there were no in-person sessions early in the pandemic due to social distancing policies.

Unlike Marc and Jamie, Kim talked about what she was going through at the hospital with a therapist.

Every two or three weeks they met. Kim told the therapist about the patients who asked her if they were dying. She talked about the families who had to choose one person to be present for a relative's death.

If Kim needed time to process a sad event, that was OK, the therapist assured her.

"There's no real 'fix' to them," Kim said. There was "just sitting with the discomfort of the emotions, and then taking time to do things that are rejuvenating to me."

A resident is tested

One day in January, Jamie was just about to begin a shift in the pediatric emergency room when he realized something was wrong. His nose was congested.

He’d noticed the congestion earlier in the day, and thought it might be allergy-related.

The discomfort lingered. Although it was the only symptom, something about it felt different.

Jamie told the shift supervisor that he needed to get tested. He would have to go home until he received confirmation that he did not have the virus.

His unit included children on chemotherapy and others with compromised immune systems. These patients would be vulnerable to severe illness if they caught COVID-19. Jamie hated to leave the department down a doctor, but he could not risk exposing sick children to the virus.

In hospitals across the country, doctors were making similar decisions. COVID-19’s emergence had forced them to monitor their own health more closely than ever. Older medical staff remembered another coronavirus, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, in 2003, and the threat it had posed to medical staff.

Health care workers accounted for a little more than one in five of the 8,100 people infected by SARS.

Jamie called his wife, Sarah, an emergency care nurse, and they both got tested for COVID-19. They collected their children from school. And the family went into quarantine that day, pending the test results.

They didn’t have to wait long. That night Jamie and Sarah learned they both had COVID-19. Although their symptoms were mild, the whole family stayed in quarantine for two weeks.

It was the middle of the winter and the days were too cold to do much outside, so Jamie and Sarah spent time teaching the children in order to make up for the lessons they were missing. They also engaged in family activities: baking cookies and homemade pizza; playing dress-up games; and setting up the children’s inflatable bounce house indoors.

Jude and Ari saw the two weeks at home with both parents “as a huge win,” Jamie said.

At times, though, Jamie felt guilty about how much fun they were having. The doctor wondered how he’d caught the virus. Had he let down his guard?

Whatever the case, the result was the same. He was not there in the trenches with his colleagues, treating the other pandemic patients.

“After the first week of quarantine,” he said. “I was itching to get back.”

A little more than a month after their bouts with COVID-19, Jamie and Sarah would have cause to celebrate.

On March 2, Sarah gave birth to their third child, a daughter, Nina.

'The vastness of what I don't know'

By the end of January 2021, Wisconsin’s spike in COVID-19 cases had passed. On Feb. 1, the state reported 1,082 cases and 20 deaths.

March 1: 514 cases and eight deaths.

July 1: 87 cases and two deaths.

The first of July signaled the end of the first year of residency for Kim, Marc and Jamie. They were no longer the new doctors.

The next crop of first-year residents had arrived.

For Kim, now 30, the anniversary was less momentous than she had expected. She noticed the easy camaraderie among the new first-year residents, and attributed much of it to the fact that they had gone through orientation in person, something her group had been unable to do.

When she looked back upon the year, she concluded, “I’ve identified better the vastness of what I don’t know.”

For Marc, the year offered a lesson about death: "People often think of it as a failure of our efforts as physicians if a patient dies," he said. "During the early days of COVID, watching individuals die alone, I began to think more about the process of dying. I think having watched individuals die in the hospital, death has become normalized."

He continued: "The big change for me has been thinking about the process of dying, and how we can help patients pass in a way that they want."

Jamie couldn’t believe a whole year had passed. One month, he’d been starting in a new department, the next month rotating to another.

Jamie asked himself: “Do I have a year’s worth of knowledge? Do I know everything I need to know?”

The more he thought about it, the more he realized how much he had grown in “knowledge, experience, wisdom and attitude.”

He worked more efficiently now, diagnosing patients more quickly.

He felt so grateful to have arrived at the end of the first year.

“At least early in July,” he said weeks later, “we had the sense that we really did cross the hump in terms of COVID and got through it.”

He paused and reconsidered that sense of hope.

“Who knows with this delta variant,” he added, “but that was the initial thought.”

Mark Johnson has written in-depth stories about health, science and research for the Journal Sentinel since 2000. He is a three-time Pulitzer Prize finalist and, in addition, was part of a team that won the 2011 Pulitzer Prize in Explanatory Reporting for a series of reports on the groundbreaking use of genetic technology to save a 4-year-old boy.

Email him at mark.johnson@jrn.com; follow him on Twitter: @majohnso.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: New Milwaukee doctors fight pandemic while facing their own fears