Tribal members in Wisconsin spear fish through ice not just to feed, but to teach community

MOLE LAKE – Excitement filled the Mole Lake Rec Center as 13-year-old Ganebik Johnson and the other children and adults gathered around the Ojibwe tribal elders as they prepared to fillet the day’s catch of muskies for the community.

Dozens of Ojibwe from different bands in Wisconsin had spent the January day on a frozen Pelican Lake in Oneida County, telling stories around holes dug through the ice, waiting for a chance to spear a musky.

They had caught almost 10 of them that day, with many being about two feet long, during the annual Ishpaagoonika Deep Snow ice spearing camp.

After the muskies are filleted, they’ll be soaked in milk overnight to remove some of the fishy taste, then smoked and distributed to elders and the Mole Lake Ojibwe community on the reservation.

Ganebik is nearing the age when he’ll be mentoring other children and even some adults on how to spear the traditional way at these camps. That’s exactly what tribal elders and organizers hoped for when they started the camps in 2018.

“A lot of the kids had never done this before, nor had their parents, because they were raised in the cities and they were moving back to the reservation,” said Mole Lake elder Wayne LaBine, who started the camps.

“Initially, it was for kids, but we also started bringing adults. So, it grew over the years. … A lot of adults and kids come out to learn how to fish, hunt, gather rice and (collect) maple syrup in the spring.”

Before gaming helped vitalize the economy on reservations in Wisconsin, many tribal families were forced to moved to cities, such as Milwaukee, for work and housing.

Today, with more financial leverage, many tribes have been able to build economies slowly, as well as apply for more federal grants for housing projects and other needs.

While that revitalization attracted some families to come home generations later, many had forgotten much of the traditional ways of spearing, hunting and ricing.

Tribal elders saw that as an opportunity to also revitalize the culture — especially LaBine who’s a member of the Voigt Task Force, which helps to ensure Ojibwe people maintain their treaty rights.

Many Ojibwe view hunting and fishing, especially off-reservation in northern Wisconsin, almost as a duty to maintain hard-fought treaty rights.

Ojibwe territory had once included much of northern Wisconsin, but 22,400 square miles were ceded to the U.S. government through treaties in the mid-1800s for extraction of timber and other resources.

Tribal leaders at the time made sure the treaties included the right for Ojibwe to continue to harvest, hunt and fish in the Ceded Territory.

Those particular treaty rights were largely forgotten or ignored by state officials in the 20th century, but some Ojibwe people would still clandestinely exercise those rights to hunt and fish off-reservation.

In 1973, two members of the Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe Tribe in Wisconsin intentionally allowed themselves to be caught spearfishing through an icy lake. They wanted to bring their case to court, armed with the facts of the U.S. treaties.

Federal courts eventually upheld those rights, and Ojibwe people started openly to fish off-reservation, outside of the state-mandated fishing season, to the ire of many non-tribal people who started protesting.

Some of those protests became violent in the 1980s during a period known as the Walleye Wars.

Today, there are still isolated incidents of harassment against Ojibwe spearfishers, especially in the early spring, during walleye season.

Pelican Lake, where the annual Mole Lake ice spearing camp is held, is off-reservation in the Ceded Territory, but tribal members say there've been no issues of harassment during the camp's five years.

While the lake is about 12 miles from the Mole Lake Reservation, tribal historians say the reservation once extended to the edge of Pelican Lake, because that’s where tribal members had always had ice spearfishing camps.

But the original treaty documents showing reservation boundaries had been lost during a shipwreck and, by the time a new treaty was drawn up, non-tribal settlers had already taken up much of the land around Pelican Lake.

The Ishpaagoonika camp also includes workshops and Ojibwe language classes at the rec center. During one workshop, the students drew and carved wooden fish paddles.

Instructor John Johnson Sr., who's also the president of the Lac du Flambeau Ojibwe Tribe in northern Wisconsin, explained that the fish paddles were designed by his people as a way to fish clandestinely overnight, when Ojibwe spearfishers in the past would try to hide from Department of Natural Resources game wardens.

He said one way to keep the hole in the ice from freezing back to ice overnight was to pile snow over it.

After the muskie catches during the Ishpaagoonika camp Johnson laid asemaa (tobacco) on the fish to give thanks to Creator, as is the Ojbiwe custom.

It’s been a little warmer this winter, so some parts of the ice on the lake were slushy on top as the campers set up tents in several places around the lake.

Non-tribal anglers also had set up tents on the lake. In Wisconsin, only Ojibwe tribal members are allowed to use spears to fish on many lakes, including Pelican Lake, while others may use hook and line.

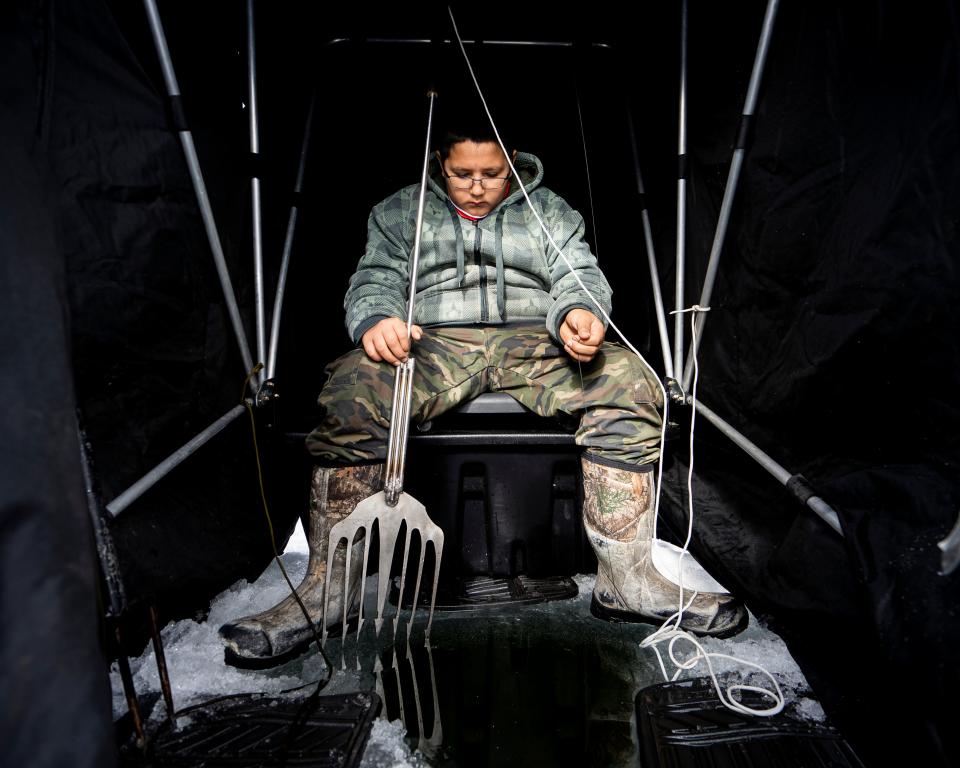

After digging holes in the ice, they sat around them holding “jigging” sticks with colorful fish decoys attached by lines to them.

Elders at times tell traditional stories to the children while waiting, such as about Wenaboozho, an Ojibwe folkloric hero and original man, that include life lessons.

Campers were taught to jiggle the sticks to move the decoy to attract muskies. The muskies wouldn’t bite the decoy but would come because they were curious. That’s when a spearer may only have a few seconds to catch the fish.

“We teach the youth all the things we’ve learned within our culture and with spearing,” said John Johnson Jr., who’s been coming to the camp the last three years with his family.

Cassandra Graikowski now helps organize the camps every year, which doesn’t just include the ice spearing event, but others, depending on the season, such as for wild rice and rabbit snaring.

“This was all taken away from us,” she said. “I didn’t know this. Now, we’re bringing it back.”

Graikowski said grant funding helps purchase the equipment for the camps, such as boats, all-terrain vehicles and snowshoes.

Chris McGeshick, former Mole Lake Tribe chairman, said the camps are made possible with the work of Graikowski, elder instructors and commitments from the tribe, the community and the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission, which represents the Ojibwe tribes in Wisconsin, Michigan and Minnesota in managing natural resources.

“My dad, my uncles, my aunties and my mom always told me we need to share what we’ve learned,” he said.

Frank Vaisvilas is a former Report for America corps member who covers Native American issues in Wisconsin based at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Contact him at fvaisvilas@gannett.com or 815-260-2262. Follow him on Twitter at @vaisvilas_frank.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Wisconsin tribal members spear fish through ice teach community