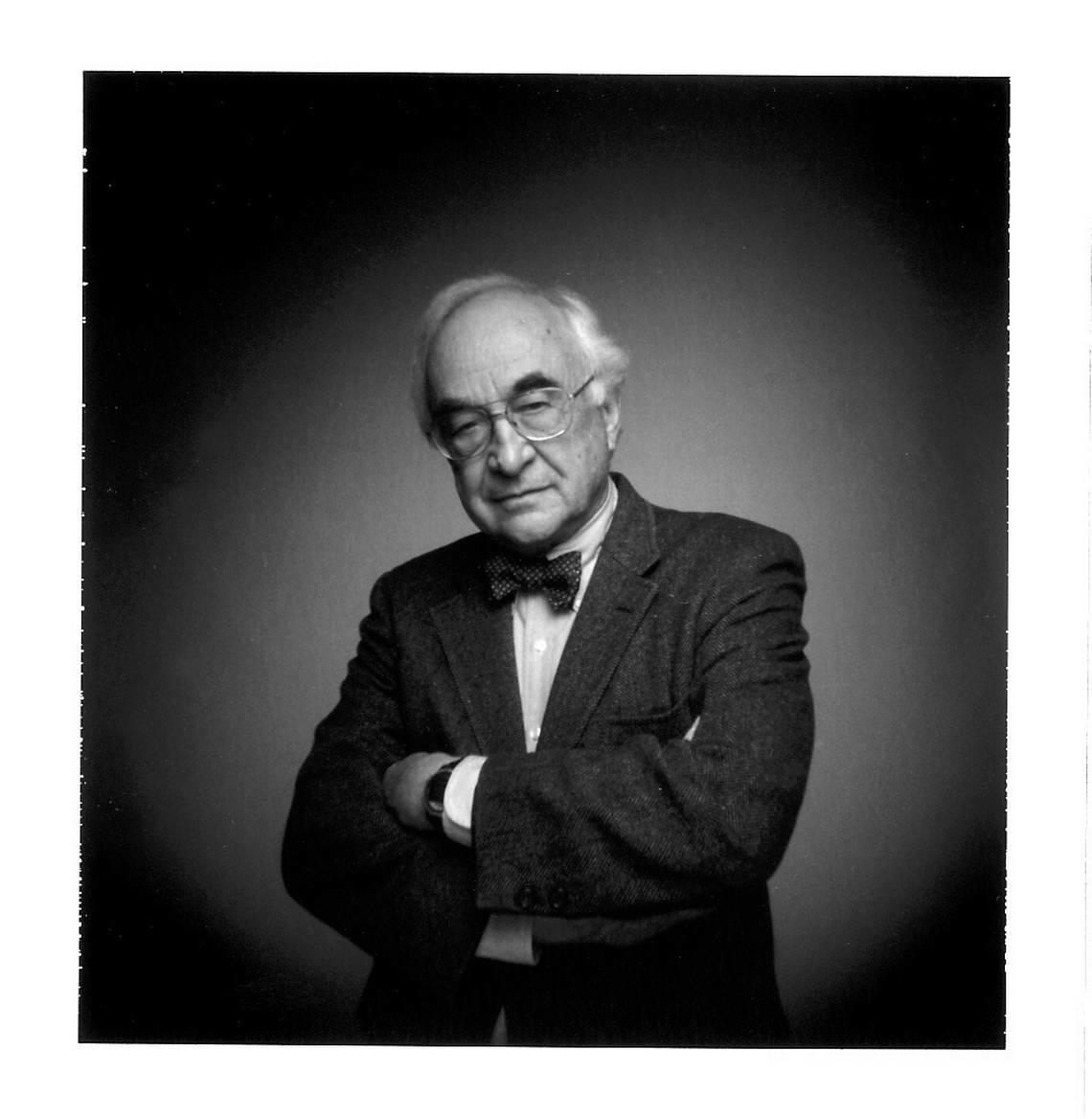

A tribute to Philip Meyer, UNC professor and father of computer-assisted reporting

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Philip Meyer, the longtime UNC-Chapel Hill journalism professor who brought a scientist’s toolbox to the nation’s newsrooms, leading a surge in computer-assisted reporting that heightened what was possible with a pad and pen, has died.

He was 93, and died from complications of Parkinson’s disease Nov. 4 at his home in Carrboro.

Over his long career in both newspapers and academia, he became a thoughtful advocate for data-driving work as a means for reaching deeper truths. His 1973 book “Precision Journalism” served as a must-read text for generations of students and budding reporters, enduring through four editions.

“Everything I’ve thought about data journalism, Philip Meyer thought first and better,” said Will Craft, data editor for investigations at The Guardian, in a recent tweet.

Meyer’s early work with spreadsheets got scoffed at by Luddites in the profession, who saw computers as the province of number-crunchers with advanced degrees — not street-wise scribes. But as the machines grew more accessible and affordable, they found their way into everyday reporting under Meyer’s guidance.

“For journalists, these methods still beat the educated guesses, thumb-sucking and haphazard data collection of the past,” he wrote in “Precision Journalism.” “Scientific method is still the one good way invented by humankind to cope with its prejudices, wishful thinking, and perceptual blinders.”

‘There’s an application for journalists here’

Born in Nebraska in 1930, he grew up in rural Kansas in a farmhouse powered by a pack of six-volt batteries and heated by a fireplace that had corncobs for kindling, he recalled in his 2012 memoir, “Paper Route.”

He found his way into newspapers inspired by Clark Kent, seemingly as powerful behind a typewriter as when bending steel bars as Superman. Meyer “fine-tuned his identity as a mild-mannered reporter” while working for The Collegian at Kansas State University, his family recalled in his obituary. After a brief stint in the Navy, he took an assistant editor’s job at the Topeka Daily Capital.

In Topeka, he met fellow news-gatherer Sue Quail, who would write the couple’s wedding announcement. Shortly after their 1956 marriage, they would drive to Chapel Hill so Meyer could complete a master’s degree in political science.

He would work reporting jobs in Miami and Washington, but his calling emerged during a 1966-67 Nieman fellowship at Harvard University, where he would delve into social science techniques. In his Nieman year, he would learn to perform statistical problems on an IBM 7090 — cutting-edge technology at the time but too physically large to fit on a desk.

“Once I saw what I could do with that, I thought, ‘My God, there’s an application for journalists here,’ “ he said in a 2008 interview for the Nieman Foundation. “This made me feel so big and strong, even though I only had three minutes of computer time over the whole semester.”

Covering Detroit unrest, winning a Pulitzer

His breakthrough came in 1967 following the race rioting in Detroit, in which Black residents clashed with police over five days, leading to 43 deaths and more than 400 buildings destroyed. Meyer took a call from an exhausted newsroom looking for other Knight Ridder reporters to fill in for the staff, and he nominated himself.

He worked on the theory that the rioters’ demographics and motivation were poorly understood, and in cooperation with the Urban League, he arranged for volunteers to pass out questionnaires to more than 400 Black citizens.

His findings would change ideas about the nature of Black unrest in Detroit and help the Free Press win a Pulitzer.

Essentially, the data Meyer would cross-tabulate showed that the rioters were largely native Detroiters rather than migrants.

“This explodes whatever remained of the theory that race riots are caused by Southern Negroes who can’t adjust to the pressures of big-city life,” he wrote at the time.

He dug into education levels, income, political leanings and attitudes toward government, developing what had been a poorly understood profile.

“In their alienation, the rioters display some similarities to hippies,” Meyer wrote. “Both feel that the world is wrong, and they want to set themselves apart from it. But hippies accept their share of the world’s guilt while rioters project it. The hippie hands you a flower and says “Peace.” The rioter shouts “Get Whitey” and throws a rock.”

Returning to UNC

Meyer returned to UNC as a professor in 1978, becoming the school’s first Knight Chair in Journalism a few years later. He would lecture on six continents and become beloved by generations of students, advising on 72 theses and dissertations. Through many honors, he remained a mild-mannered lover of forest walks, chocolate, jokes and old cameras, on which he took trunks full of family pictures.

“He was witty,” said his daughter, Kathy Lucente. “He had a good sense of humor. He was humble, and he loved finding people in the room he could share successes with.”

Into his last years, he remained in tune to changes both in journalism and social science, predicting hard times for newspapers in the information age but resilience for journalists willing to adapt.

“If newspapers fail, our sense of community is going to fail,” he told The N&O in 2008, “and if our sense of community fails, our democracy will fail. And there are already signs that it’s happening. ... If we can’t keep something like newspapers keeping the public informed, then we’re in big trouble.”

Meyer is survived by his brother John, daughters Kathy Lucente and Melissa and Sarah Meyer and many grand and great-grandchildren. Sue Quail Meyer died in 2001.

A funeral service will be held at Chapel of the Cross in Chapel Hill at 10:30 a.m. on Dec. 2.

Donations can be made to The Fund for PhD Education and Enhancement in memory of Phil Meyer, in care of UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media, ATTN: Danita Morgan, CB# 3365, UNC-Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, 27599-3365