Tributes to influential African Americans abound in Indianapolis. Why not visit a few?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Indianapolis is filled with salutes to influential Black Americans.

Here’s a look at some of the places named for African Americans who helped shape Indianapolis and America.

Crispus Attucks High School

1140 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. St.

In 1770, Crispus Attucks was the first American to die in the Boston Massacre, a precursor to the American Revolutionary War.

Crispus Attucks High School opened as a segregated school for Black students in 1927, reversing the integrated school system.

The school’s Crispus Attucks Museum houses memorabilia from the first all African-American high school in Indiana.

317 Project: Black voices share Black History loud and clear

Beckwith Memorial Park

2302 E. 30th St.

Attorney and civil rights activist Frank R. Beckwith was born in Indianapolis in 1904 to former slaves.

He was the first African-American person to run as a candidate for president of the United States and was instrumental in the naming of Douglass Park (now Frederick Douglass Park) and the paving of Martindale Avenue.

Beckwith Memorial Park was dedicated in 1970.

Elwood & Mary Black Park

4241 Fairview Terrace

Elwood Black was a public servant, community activist, and advocate for union labor and civil rights issues. Elected Indianapolis-Marion County City-County councilman for district 6 in 1991, he served on the community affairs and metropolitan development committees. He worked as a basketball coach, maintenance worker, and delivery driver, and he served as president of United Auto Workers Union Local 550.

Julia M. Carson Transit Center

201 E. Washington St.

Julia M. Carson was the U.S. Representative for Indiana's 7th congressional district from 1997 until her death in 2007. During her tenure in Congress, she helped secure federal funding for the $26.5 million transit center.

Carson was born Julia May Porter in Louisville, Kentucky, and, as a girl, moved with her mother to Indianapolis. She graduated from Crispus Attucks High School in 1955, and attended Martin University in Indianapolis and Indiana University - Purdue University Indianapolis.

In 1965, she was working as a secretary at UAW Local 550, when newly-elected congressman Andrew Jacobs Jr., hired her to do casework in his Indianapolis office and later encouraged her to run for the Indiana House of Representatives. She won election from the central Indianapolis district in 1972, and then was re-elected, before being elected to the Indiana Senate where she served 14 years, eventually holding the minority whip position before retiring in 1990.

Carson, the first woman and first African American to represent Indianapolis in the U.S. Congress. She never lost an election throughout her entire career in both state and federal politics.

Her grandson André Carson succeeded to her seat following her death.

The transit center is the hub for public transit in Indianapolis, serving pedestrians, cyclists, and transit riders.

The Julia Carson Government Center

300 E. Fall Creek Parkway, N. Drive

The center was named for Carson in 1997. As Center Township trustee before she was elected to Congress, Carson bought the building for $5 million, ordered $7 million in renovations and found tenants to fill it to capacity.

In 2011, Ivy Tech Community College named its new library and community space at Illinois and 27th streets the Julia M. Carson Learning Resource Center.

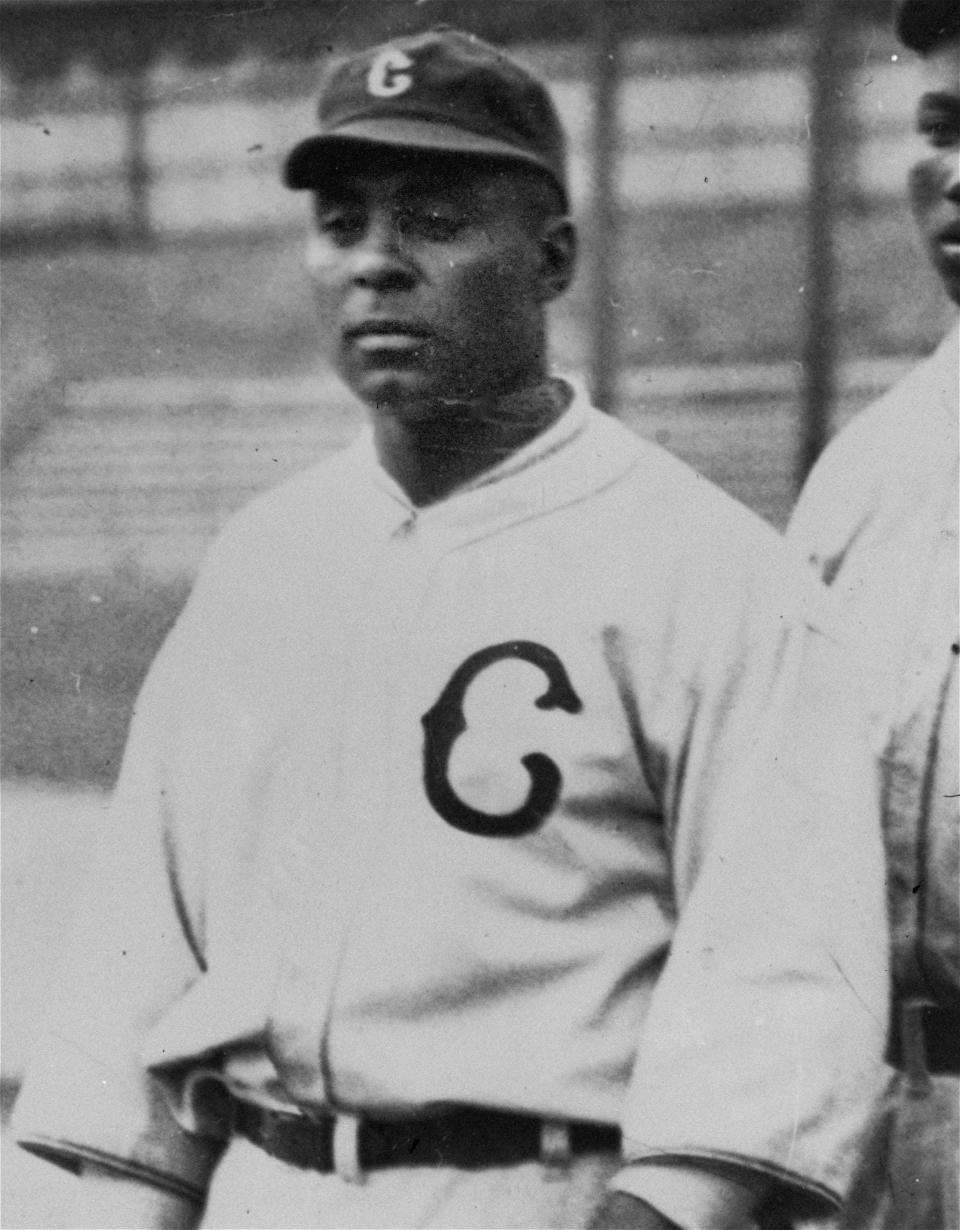

Oscar Charleston Park

2800 E. 30th St.

One of the most influential contributors to the Negro League baseball teams in Indianapolis, Oscar Charleston was born and raised in the city alongside his 10 brothers and sisters. He spent 33 seasons playing for and managing the Indianapolis ABCs, the Chicago American Giants, and other Negro League teams. He retired from baseball in 1945 and worked as a baggage handler for the Pennsylvania Railroad. In 1976, Charleston's contributions to baseball were recognized through his election to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Doris Cowherd Park

4050 N. Irvington Ave.

Doris Cowheard was born in 1899, the daughter of share-croppers who moved often.

She moved to Indianapolis in 1923 and married, raised a family, and began her career at the Flanner House where she cooked for 25 years while teaching canning and gardening as a means toward self-sufficiency. A role model to the young people who lived in her neighborhood, she was instrumental in establishing the concept of neighborhood participation and cooperation. She encouraged her community to get involved with the parks, especially the one named now named for her.

Babe Denny Park

900 Meikel St.

Edward Bay "Babe" Denny, the first African-American motorcycle officer in the Indianapolis Police Department, managed Ray Street Center and Miekel Street Park in the 1940s. He later was a consultant to the mayor.

Frederick Douglass Park

1616 E. 25th St.

Born a slave in 1817 in Maryland, Frederick Douglass escaped to freedom to become one of the leading abolitionists of his time. He moved to Massachusetts, and attended anti-slavery meetings where he gave speeches on the topic, gaining notoriety and being appointed to the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. Douglass founded and published his own anti-slavery weekly newsletter, "The North Star," and wrote “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass,” among other abolitionist books.

John Ed Park

2000 E. Roosevelt Ave.

John Ed Washington grew up in Indianapolis a dedicated basketball player. As a student at Arsenal Technical High School, he co-captained the basketball team in his senior year and carried an 18.5 point per game average. He was the star player at the University of Evansville's men’s basketball team. His honors include All-City player, All-Sectional player, and a chance to play for the 1974 Indianapolis City Championship basketball team. Washington was a member of the University of Evansville basketball team that died in a plane crash in December 1977. He was 21.

Mari Evans mural

448 Massachusetts Ave.

Mari Evans was a renowned poet, author, and playwright who spent the bulk of her writing career in Indianapolis. She’s best known for her poems “Celebration” and “I Am A Black Woman.” Evans died in 2017.

Michael “Alkemi” Jordan painted the 30-foot-tall mural in 2016.

James Foster Gaines Park

2100 N. Tibbs Ave.

Born and raised in Indianapolis, James Foster "Bruiser" Gains served 27 years with the Indianapolis Police Department, devoting much of his time, energy, and resources to mentoring the youth and assisting people in need throughout the city.

He attended Crispus Attucks High School, playing football and basketball, and then served in the U.S. Navy from 1944 to 1946 and managed the PAL (Police Athletic and Activities League) project.

JTV Hill Park

1806 N. Columbia Ave.

Born in 1855 in Ohio, James T.V. Hill moved to Indianapolis in his early years. He was active throughout the community, and served as a deputy prosecuting attorney in Marion County.

Hill was first employed in Indianapolis as a postal clerk and later as a barber. He graduated from Central Law School in 1882 and was one of the first Black attorneys admitted to the bar in Indianapolis.

Martin Luther King Jr. Park

1702 N. Broadway St.

Georgian-born Baptist minister Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. became nationally known as a proponent of civil rights and racial equity through nonviolent demonstrations, including the civil rights march on Washington, D.C., in 1963, speeches, and conferences with national and international leaders. His efforts led to the establishment of the Civil Rights Act of 1942 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

Graham E. Martin Park

1302 Fall Creek Parkway E. Dr.

A graduate of Crispus Attucks High School, Indiana University and Howard University, Graham Edward Martin enlisted in the U.S. Navy, where in 1944 he was selected as one of the first 13 African-American men to train to become officers. Martin served four years in the Navy as a lieutenant junior grade ship commander. He coached varsity football and baseball at Crispus Attucks from 1947 to 1982.

“Reggie, Reggie, Reggie! Boom, Baby!” Reggie Miller mural

127 E. Michigan St.

This 60-foot-tall mural honors Pacers legend and Basketball Hall of Famer Reggie Miller.

Artist Pamela Bliss painted it in 2018.

Wes Montgomery Park

3400 N. Hawthorne Lane

Self-taught guitarist Wes Montgomery launched his music career in Indianapolis, becoming recognized as one of the world's greatest jazz guitarists. Montgomery won every notable honor possible for a jazz musician during his career and was at the height of his fame at age 45 when he suffered a fatal heart attack.

Al E. Polin Park

100 E. 29th St.

A life-long resident of the Mapleton-Fall Creek area, community activist Al Polin has promoted parks to local youth, and has served on the Indianapolis Community Policing Board, with the Indianapolis Neighborhood Resource Center and on the Drug Free Indiana Commission.

Polin worked as a coordinator for the Quality of Life Human Relations at the Allison Division of General Motors.

Andrew Ramsey Park

310 W. 42nd St.

Having moved from Tennessee with his family, Andrew William Ramsey graduated from Manual High School in 1925 and obtained a B.A. in Romance languages from Butler University and a master’s degree in French from Indiana University. Ramsey was an instructor in Romance languages at the University of Louisville's Municipal College. He was involved with the NAACP, the Indianapolis Urban League and the Indianapolis Museum of Art, and was a long-time columnist for the "Indianapolis Recorder."

Ransom Place Park

801 N. Indiana Ave.

Influential lawyer, businessman and civic activist Freeman Bailey Ransom moved to Indianapolis in 1910 after completing his law degree and became part of the success behind the Madame C.J. Walker Company, serving as the company's attorney and general manager. Ransom was a member of the Indianapolis-Marion County City-County Council and served as a legal consultant for the NAACP.

Bertha Ross Park

3700 N. Clifton St.

As president of School 41's PTO, Bertha Ross organized a baseball league for children between the ages of seven and 15. Each year, she and her husband would raise money to outfit 12 team with other groups and businesses helping to sponsor the teams by raising money to furnish bats, mitts, uniforms and coaches. Anyone within the age limits could play in this league, with one caveat: They could not get into any trouble.

Rev. Mozel Sanders Park

1300 N. Belmont St.

Minister and community leader Mozel Sanders came to Indianapolis from Cleveland, Ohio, in 1945. He worked at a foundry during the day and preached at a local church at night. In 1959, he became the pastor of the Mount Vernon Missionary Baptist Church, serving there until his death in 1988. Sanders hosted a daily radio program and was the founder of a national job training program. He started serving Thanksgiving dinner to less fortunate families in Indianapolis, which is a tradition that lives on today, through the Mozel Sanders Foundation Inc.

Juan Solomon Park

6100 Grandview Dr.

Highly involved in civic activities with the Indianapolis and African-American community, Juan Solomon served as director of the Community Service Council and the Indianapolis Urban League, he was a board member of the Indianapolis Department of Parks and Recreation. He also served on the Mayor's Employment Task Force, and worked for Eli Lilly for 32 years.

John Stewart Basketball Court

Gardner Park, 6925 E. 46th St.

In 1999, John Stewart was an 18-year-old stellar Indiana hoopster.

The 7-feet-tall Lawrence North star player was signed to play basketball for the University of Kentucky.

During a game against Columbus North High School, Stewart collapsed shortly after complaining of shortness of breath and died at the hospital from a previously unknown heart condition. His mother now runs the John Stewart Foundation, which promotes cardiac screening for youth.

Stanley Strader Park

2850 Bethel Ave.

A lifelong resident of the southeast side, Stanley P. Strader was born in 1939.

At 17, he joined the U.S. Marine Corps. After that, he served in the Air Force.

He studied urban affairs at Lane College and worked at Indianapolis Public Schools in the Human Resources Department, and at Camp Atterbury as the recreation program director.

In 1969, Strader began working with the Community Action Against Poverty and the United Southside Community Organization. He founded the nonprofit organization Watoto-Wa-Simba (The Young Lions) Inc. in 1971, initially with a youth advocacy focus, but going on to serve senior citizens as well.

Stanley Strader Park: Name honors southeast side advocate who lifted his community

He was elected to the Indianapolis-Marion County City-County Council in 1980, delivering city funding for improvements to Bethel Park (which would later be renamed to honor him), the restoration of the fountains in Fountain Square, and the Bean Creek drainage project.

He started after-school programs and raised money to take busloads of youths on field trips and to amusement parks out of state.

Talley Park

5900 E. 38th St.

Eva C. Talley-Sanders is a deputy chief for the Marion County Sheriff's Office, the first African-American woman to hold that rank in the department. Talley Park is named for her family, including her brother, Steve Talley, who was a Indianapolis-Marion County City-County councilman, and their parents Eva M. Talley and Van Lawson.

Major Taylor mural

11 S. Meridian St.

Born in Indianapolis in 1878, Marshall Walter “Major” Taylor earned his nickname by performing cycling stunts while wearing a military uniform as a child outside of a bike shop.

Although he began his bicycle racing career in Indiana, Taylor was unable to train in the area because of racial prejudice, so he moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, to live and train to go on and gain national and international acclaim. He became the first Black athlete to achieve championship status in any competitive sport; and after a 16-year racing career, he retired with three U.S. championship titles and two world championship titles.

He died at age 53 in 1932.

The five-story mural, painted by Shawn Michael Warren on the east-facing wall of the Barnes & Thornburg building at Meridian and Washington streets, was part of the Art Council's Bicentennial Legends series. It was unveiled in 2021.

Major Taylor marker

Monon Trail

A historical marker alongside the Monon Trail.

Major Taylor Velodrome

3649 Cold Spring Rd.

The Madam C. J. Walker Building

617 Indiana Ave.

Built in 1927 to house the product manufacturing of Madam C.J. Walker, the building had a drugstore, a beauty salon, a beauty school, a restaurant, professional offices, a ballroom and a 1,500 seat theater.

Walker was born Sarah Breedlove to former slaves in 1867 on a Louisiana plantation. She went from being an uneducated farm laborer and laundress to one of the twentieth century’s most successful, self-made women entrepreneurs. She moved to Indianapolis in 1910 to grow her business of hair care products for African Americans, selling the products from the building and making real estate investments to become a millionaire.

The building houses the Walker Theater and the Madam Walker Legacy Center.

Madam C.J. Walker mural

Indianapolis International Airport, Concourse A, 7800 Col. H. Weir Cook Memorial Dr.

The mural shows Walker’s accomplishments with scenes of her haircare product empire.

It was created by local artist Tasha Beckwith.

Watkins Park

2360 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. St.

A pastor at Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church for eight years and a minister at St. Paul AME Church before that, Charles Watkins was deeply involved in the Indianapolis community. He served on the Mayor's Commission on Human Rights including two years as its president. He was also the president of the Indianapolis Social Workers Club and was involved with the YMCA.

William Whitfield Plaque

Watson McCord Park, 3600 Watson Rd.

William Whitfield was a 12-year veteran of the Indianapolis Police Department when, in 1922 while on patrol in a predominantly white neighborhood, he was fatally shot. He was the first Black officer shot in the line of duty in Indianapolis.

The plaque commemorates his service.

Rev. Charles Williams Park

3252 Sutherland Ave.

Rev. Charles Williams was instrumental in the development of the Indiana Black Expo, and served as its president from 1938 to 2004. Ordained in 1979, Williams helped shape many Indianapolis organizations including the Indiana Sports Corporation, the Indianapolis Downtown Promotion Council, the Indiana Convention and Visitors Association, the Indianapolis White River State Park Development Commission, and the Greater Indianapolis Progress Committee. He also served as a special assistant to the mayor from 1976 to 1983.

Frank Young Park

1000 Udell St.

Frank F. Young was born in Indianapolis in 1873, the last child in a family of six children. Starting his ministry in 1892, he served at both Olivet and Garfield Baptist churches. In 1907, he became pastor of the First Baptist Church North Indianapolis, staying there for the next 60 years and oversaw its relocation twice to accommodate membership growth.

Museums and attractions in Indiana

Evansville African American Museum

579 S. Garvin St., Evansville, Indiana

The museum features exhibits showcasing the contributions and achievements of local African Americans in fields such as art, education, and business, as well as their role in shaping Evansville's history and culture.

Evansville news: Two streets renamed to honor musician, museum founder

The Landmark for Peace Memorial

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Park

1702 N. Broadway St., Indianapolis

The memorial is dedicated to the memory of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, celebrating their legacies and symbolizing the struggle for civil rights and equality and the efforts of the African-American community in the state and across the country to promote justice and peace.

Lick Creek African American Settlement

Hoosier National Forest, Bedford, Indiana

The Lick Creek African American Settlement was established by formerly enslaved Black people and their descendants in Orange County in the early 1800s to become one of the first African-American communities in the state.

Led by Jonathan Lindley, eleven families traveled with a group of sympathetic Quakers in search of a new land which forbade slavery. Lindley settled in Orange County in 1811, five years before the county was established and Indiana became a state.

The site is now protected by the USDA Forest Service and is open to visitors to provide a glimpse into the lives of early African-American settlers in Indiana and its part of the state's cultural heritage.

Ransom Place Historic District

Established in 1897, Ransom Place is the oldest African-American neighborhood in Indianapolis. Named after Freeman B. Ransom, an attorney and general manager for the Walker Manufacturing Co., the neighborhood originally consisted of four dozen homes on six city blocks.

At its peak, it was the site of numerous Black-owned businesses, including churches, clubs, community centers, restaurants, shops, and theaters. Ransom’s son, Willard Ransom who was a local chapter NAACP president in the1940s and 1950s, also lived in the neighborhood.

Preservationist Jean Spears moved into the neighborhood in 1987 and with fellow residents Lathan Frayser, Addie Jones, Wilma Bailey, Mary Frisby and Teresa Crawford-Cottingham founded the Ransom Place Neighborhood Association to encourage the area’s preservation as well as the promotion of its history in the face of the expansion of IUPUI.

It is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. A historical marker is in place at 706 W. St. Clair St.

Historic Roberts Settlement

276th St., western Jackson Township, Hamilton County

About 30 miles north of Indianapolis are the remains of an African-American pioneer farm community founded in 1835 by formerly enslaved people who migrated from the South. The pioneers sought economic, educational, and religious aspirations with greater freedom and fewer racial barriers. They were helped by racially-tolerant Quaker and Wesleyan neighbors. By 1840, the neighborhood included about 10 families and 900 acres of land.

Indy Black history: Newspapers, birth records, wartime photos

With access to inexpensive, high-quality farmland no longer possible for small farmers and well-paying factory jobs in Noblesville, Kokomo and Indianapolis fueling an out-migration, the settlement declined.

Today, a chapel and cemetery remain from the once thriving community.

A Roberts Settlement Homecoming occurs every July 4th weekend on the Roberts Chapel grounds.

Contact IndyStar reporter Cheryl V. Jackson at cheryl.jackson@indystar.com or 317-444-6264. Follow her on X.com: @cherylvjackson.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Parks, buildings and sites in Indy honor influential African Americans