The Trillion-Dollar Grift: Inside the Greatest Scam of All Time

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In late March 2020, Haywood Talcove, a CEO at LexisNexis Risk Solutions, was packing up his office, having sent his employees home. He was worrying about laying off his staff, his family’s health, and how he was going to manage two young kids at home during the pandemic.

But when President Trump announced an initial $2.2 trillion relief package to bail out the millions of Americans desperate for cash during the national lockdown, his concern turned away from the coronavirus. An expert in cybersecurity, Talcove has worked in both the private and public sectors, and has been raising the alarm about the government’s exposure to scams for many years. And now, it was like all of his prior analysis and warnings about fraud had just become real.

“I said, ‘Oh, my God, they’re going to allow anyone to get unemployment-insurance benefits,” he recalls. “The systems are vulnerable. All you needed was a name, a date of birth, an address, and a social security number.”

Talcove’s a proud Boston guy who moved to Washington, D.C., in 1990, and went on to help an anti-government-waste-style Republican become governor of New Hampshire. He knew the relief plan would be irresistible to scam artists and especially tempting to organized transnational criminal groups. “As soon as the CARES money was announced, we started seeing squawking on the dark web, criminal groups in China, Nigeria, Romania, and Russia — they see our systems are open,” Talcove says. He estimates that “the United States government is the single largest funder of cybersecurity fraud in the world.”

Talcove understood that he had to act. So he called the White House, trying to warn of the threat. No response. Finally, after weeks of trying to get through, one night while he was playing with his kids, he got a call from an unknown number. It was Larry Kudlow, Trump’s director of the National Economic Council. “I’m like, ‘Mr. Kudlow, I really need to warn you that you have to do something about identity verification,’” Talcove recalls, “’or it’s going to be the biggest fraud in the history of our country.’” (Kudlow didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

He says he talked to Kudlow for about 15 minutes but couldn’t get him to budge. “Kudlow’s like, ‘The money has to get out quickly. You can’t have speed and security,’” Talcove says. “But I’m like, ‘That is bullshit. Sir, that’s just not true. Now you’re never going to get the money back.’”

Eventually, he says Kudlow told him to get in touch with the folks in charge of sending out small-business loans and the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance loans. But those guys told him they aren’t seeing any fraud. “I’m like, ‘Dude, you haven’t even given out any money yet! That’s why you’re not seeing it,’” Talcove says. “I’m sending them screenshots of the dark web. I’m explaining exactly how it’s going to go down. And I tell them you are going to have a $200 billion problem on your hands if you do nothing.”

IT’S HISTORY NOW: On March 27, 2020, during the height of the pandemic, Trump signed the CARES Act, pumping more than $2 trillion into the U.S. economy. The scale of the crisis was beyond anything we had ever seen, and so was the help. The money flowed like an open spigot and saved the livelihoods of millions of people. But Talcove was right. While many breathed sighs of relief, others saw the crisis as an opportunity — a chance to steal millions.

The list of various CARES Act schemes is endless and astounding: the couple who scammed some $20 million off unemployment insurance while living as high rollers in Los Angeles; the Chicago man under indictment for selling bunk Covid tests and allegedly raking in $83 million (he has declared his innocence); the Florida minister who the feds allege faked the signature of his aging accountant, suffering from dementia, to steal $8 million in PPP loans (in a twist, the pastor has been locked in a legal battle to determine whether he’s psychologically fit to stand trial). One particularly loathsome and effective plot: offering fake meals to underprivileged children in Minnesota to reel in a whopping sum of $250 million. Noted serial liar George Santos allegedly got in on the act: He was charged with receiving unemployment benefits while he had a six-figure job in Florida. (Santos has pleaded not guilty.) Other examples are admittedly funny: A guy named John Doe got unemployment money, as did someone named Mr. Poopy Pants, and so did a person going by the name of Diane Feinstein, presumably not the senator from California.

By the government’s own accounting, we potentially dished out some $16.2 billion to folks with “suspicious” emails; $267 million was sent to the identities matching current federal prisoners, some on death row; another nearly $29 billion to people living in multiple states; we even sent out more than $139 million to dead people. California alone accounts for a whopping $20 billion in pandemic unemployment-insurance fraud.

Factoring in President Biden’s and Trump’s relief efforts, the U.S. released more than $5 trillion into the economy — the biggest bailout in history. Department of Justice Inspector General Michael Horowitz told congress that more than a $100 billion in Covid aid money may have ended up misappropriated, but many experts and members of law enforcement think the number is much higher. The AP estimates $280 billion went to fraudsters and another $123 billion was misappropriated, some 10 percent of the relief money. For his part, Talcove estimates the actual losses blow past the tallies being thrown around. “The real number is much higher. I think the government lost a trillion dollars due to fraud in the pandemic,” he says. “One trillion.”

Talcove’s number is shocking and a higher estimate than many others. There could be instances of suspected fraud that were innocent mistakes. But when I asked Biden administration officials what the number might be, they admit that they “don’t know — the actual determination comes much later.” The DOJ’s Horowitz told the AP much the same thing, saying the official accounting is “at least a couple of years away.” Whatever the actual number is, the losses will be staggering.

It must be said that this should not be a red-versus-blue blame game; given the unprecedented nature of the crisis, some feel like the Trump administration acted correctly in releasing the money as fast as possible. “My liberal friends get mad at me for saying this, but the Trump administration handled pandemic unemployment as well as can be expected,” says Michele Evermore, former deputy director for Policy in the Office of Unemployment Insurance Modernization, which handles unemployment insurance. “The problem was so dire and so vast, and people needed help immediately. There was really no choice.”

Nonetheless, debates will continue for years to come over how the money was doled out — speed versus security. The problem was so large that millions of people were at risk; the necessity couldn’t have been clearer. But the cost? One trillion dollars possibly lost to crooks, many of them our fellow citizens gouging the government during a crisis. Thousands of potential victims, not to mention all of the folks who desperately needed the money and couldn’t get it. Thousands of criminals rewarded, many totally unpunished. Now, partisan gridlock and finger-pointing in Congress over the pandemic-era bailouts may halt any legislation and leaves the outcome of reform efforts less-than-certain. And after months reporting on the problem, speaking with the Secret Service agents hunting the fraudsters, victims saddled with debts they never incurred, and an afternoon spent with a scam artist, one can’t help but have serious concerns that the next time a crisis comes around, we sure as hell might get fooled again.

ONE LAW-ENFORCEMENT agency takes the lead when it comes to protecting the U.S. government from fraudsters: the Secret Service. Jason Kane, a Secret Service veteran of more than 20 years, was stationed in New York during those early-pandemic months and knew immediately that a wave of work was heading his agency’s way. “Any time there’s a crisis — Hurricane Katrina, the BP oil spill — people take advantage. It’s human nature,” Kane says. “Today we have initiated more than 3,000 criminal cases from the pandemic. We are still trying to seize back those assets but most of the money is likely gone.”

Kane is a friendly Southern guy, in his early fifties, medium height, blue-eyed, hair gone gray. He was looking to serve after 9/11 and ended up in the Secret Service. He has traveled the world, protected our top elected officials, and busted a lot of scam artists. You can tell he’s proud of the Secret Service and likes to talk about the agency, and sees his role as constantly educational. “Everyone knows about protection, the standing beside the limo,” he says, “but our job is guarding the financial infrastructure of the country as well. We were founded to prevent counterfeiting.”

On a quiet street in Washington, D.C., around the corner from a Japanese restaurant, I met with Kane, now the deputy assistant director at the agency, in a command center of the cavernous Secret Service headquarters. The building is impressive, complete with an unfortunately not-open-to-the-public museum dedicated to the history of the service dating back to its beginnings in 1865 — also, and most inauspiciously, it was conceived the same day Lincoln was assassinated. The archive traces the notable arrests and cases, tributes to agents lost in attacks and bombings. Six agents perished in the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995. One particularly devastating section: agency artifacts recovered from its office in 7 World Trade Center, destroyed on 9/11, still covered in ash.

The command-center room, HQ for the Global Investigative Operations Center, is straight out of the Jason Bourne movies — big and windowless, with three giant TV monitors showing news events that cast light on about a dozen or so analysts huddled around workstations tracking various cases on screens. Kane introduces Special Agent in Charge Mike Peck and Assistant to the Special Agent in Charge Katherine Pierce, who walk me through the past few years of chasing fraud cases, pandemic and otherwise; turns out they’ve been very busy.

Peck had been stationed in New York early on in his career, and he says he caught a warning of what was coming when, in the aughts, NYPD detectives started telling him that gangs had shifted from selling drugs on the corner to “selling stacks of information,” he says. “It was names, dates of birth, social security, all the basic personal-identification information.”

Which goes a long way to explaining how so much data was out in the streets. When the pandemic hit, gangs and organizations had all the info ready to go. To make matters worse, we’ve all probably had our identity stolen, they tell me, and if you haven’t yet, you will. “As far as protecting your identity? Your information’s been taken,” Kane says. “Everybody’s information’s been taken at one point or another. It will reside on some bad actor’s computer at some point.”

For the fraudster, pandemic relief offered unlimited opportunity. Brett Johnson is a former hacker who helped found ShadowCrew, a wild bunch of pioneering identity thieves from back in the early aughts. Since his arrest and conviction, he has put on the “white hat,” consulting with law enforcement and security companies. Johnson says the CARES Act crimes were too easy and the window too wide: “For six months, every single fraudster on the planet pivoted to unemployment fraud. Because there was no security. ‘Let’s get it.’ Hell, they were giving money away.”

Johnson has seen everything in the hacking world. But he was shocked to watch 16-year-olds on Telegram posting how-to-steal videos during the pandemic. “Cybercrime has evolved to the point that the individual is basically plug-and-play,” Johnson says. “You don’t have to know anything to come in and immediately start to profit. Sophistication is not in the criminal.”

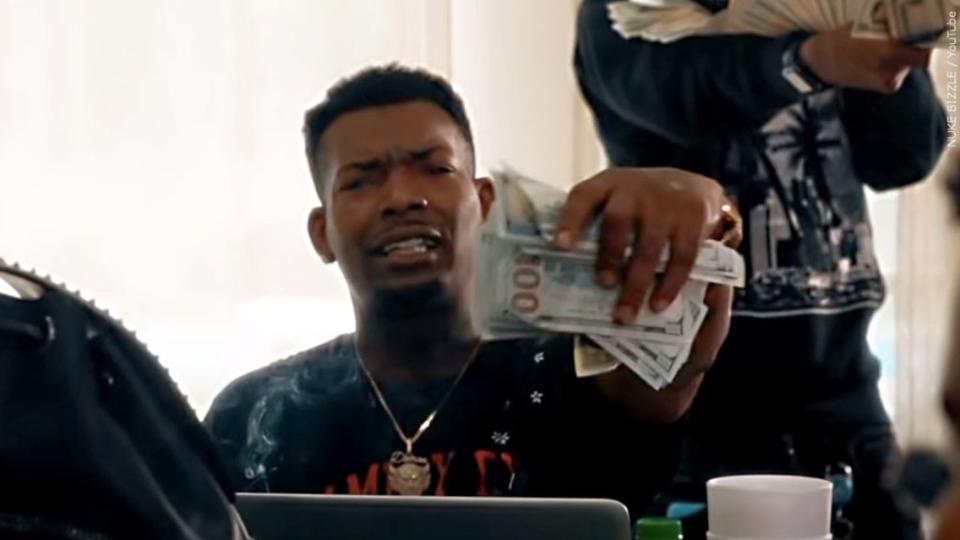

One of the more notable and least sophisticated cases was that of the rapper Nuke Bizzle, a.k.a. Fontrell Baines, who released a video detailing his ill-gotten gains and then was promptly arrested. His scheme — like almost all of the unemployment fraudsters’ — was basic: Take a whole bunch of stolen identities and file claim after claim in those early days of 2020, have the debit cards sent to an address, and hoover up the cash. Of course making a music video about all this and posting it on YouTube recalls Stinger Bell’s famous admonition to a flunky in The Wire: “You takin’ notes on a criminal fuckin’ conspiracy?”

“The video brought our attention, but Mr. Baines had some 92 claims going to two addresses, which is a badge for fraud,” says U.S. Attorney Ranee Katzenstein, who prosecuted the case. She doesn’t see Nuke as any kind of mastermind, just a sad story. “When we think about criminal organizations, we often think of a tree or a pyramid, where somebody is up on top and moving down to different groups. That’s not the model here. The model here is grass growing — because the crime is not complicated. You don’t need to be part of an organization. You can do it yourself from your mom’s basement.”

(Baines pleaded guilty and was sentenced to more than six years in federal prison.)

Katzenstein says law enforcement has had to react to large-scale fraud in times of crisis before, but the scale and ease of these crimes make the job exponentially harder. “We call it pay and chase: The government pays out the benefits, and then, if there’s fraud, we’ll try to claw it back,” she says. “That was fine in the old days. But nowadays, when with a few strokes on a keyboard you can submit a hundred applications, we can never keep up.”

THERE MUST BE thousands of stories of people who were unknowingly burned during the era of pandemic fraud. Steven and Gloria Clark’s stands out as a particularly maddening tale, a bureaucratic nightmare worthy of Kafka. The Des Moines, Iowa, family of four, with two daughters now ages four and seven, were looking to buy their dream house in 2021. They are a Black family from the heartland who’d been renters their whole lives. Home ownership was a big step to feeling more secure. They had saved the money that Steven earned working as a customer-service rep, watched their credit, and everything seemed good to go — until they got hit with an IRS bill that said they’d received $30,000 in unemployment funds from the state of California, a place they’d never lived or visited. The IRS claimed they now owed more than $5,000 in taxes. Thus began an ordeal that’s still ongoing two years later.

It’s hard to fathom the behemoth that is the American tax system on a good day, but when it comes down on your head, it’s pure misery. It’s one thing for Trump and his army of accountants. It’s another for a working family stretching like the Clarks. The IRS threatened to garnish their wages and is even now, two years later, continuing to charge them interest despite news stories and elected officials pleading their case. Not to mention the fact that they say they never received any of this money that they are being taxed over.

“It’s been an ordeal,” Gloria says. “You just get so frustrated. You’re online sending emails about it or on the phone and then your call gets disconnected. And the IRS says there’s nothing they can do. It’s just a lot of time spent trying to fix this. There have been many tears.”

(Reached for comment on the case, an IRS spokesperson said that “under federal law, federal employees cannot disclose tax returns of individuals.”)

The couple has no idea how their identities were stolen, but now they are incredibly careful in every transaction. Steven thinks one thing the government could focus on is helping victims as much as it has on enforcing the law. “They should set up a task force to help people like us navigate the system and get through this,” he says. “Because not until this is done, are we going to be good.”

Gloria adds, “For us, trust is just broken, big time.”

You would hope that lawmakers in Washington would step in and help make life easier for families like the Clarks and work to prevent things like this from happening again. The Biden administration responded this March by putting forth a $1.6 billion, three-part Pandemic Anti-Fraud proposal: pledging to continue prosecution and investigation of criminal syndicates (“They may run, but they cannot hide,” the administration warned); investing in prevention of identity theft and major fraud (one huge step would be to modernize every states’ antiquated and vulnerable IT systems and allow for better interstate communication); and helping the millions of victims of identity theft via early warnings and remediation.

“We think this a proposal that actually tackles the problem, and everyone should support,” a White House official tells me. “We will recover far more than we spend. It will both go after bad guys targeting federal programs and increase deterrence. This whole bill is a saver. We will net dollars for the U.S. government.”

Alas, with the GOP in control of the House, the proposal’s fate remains unclear. Rep. James Comer of Kentucky, chairman of the House Committee on Oversight and Accountability, has been leading hearings probing pandemic-era fraud and vowing to bring “accountability to Washington,” saying, “We owe it to the American people to get to the bottom of the greatest theft of American taxpayer dollars in history.” However, Comer’s also a partisan warrior who’s been locked in on Hunter Biden and accused by the AOCs of the world of targeting blue states like New York while overlooking fraud in red states like Arizona — and thus far has ignored the Trump administration’s role in doling out money in the pandemic. Also, Comer’s track record is more than a little shaky. According to the Daily Beast, in a bit of GOP anti-regulatory fervor, he previously tried to pass two bills that would have diluted government oversight that might have prevented such widespread fraud in the first place. (Comer’s office didn’t respond to requests to for comment.)

Partisan gridlock would be the worst option. There could also be a desire to memory hole this entire unfortunate experience: Being taken in a fraud is something everyone would rather forget, but that does not make sound policy. The Biden plan is a much-needed first step. As the White House official says: “Criminals need to know they can’t take advantage of this country during a crisis.” Whichever direction the policy fights go, one thing is clear: taking no action will allow the criminal element to thrive and find new routes into our collective pocketbooks.

IN A SMALL CITY with some rough neighborhoods, I meet up with a woman I’ll call Danni. She’s Black, pretty, streetwise, her eyes sparkle and don’t miss much. She’s got kids. Lives in a neighborhood near where she was raised, with lots of street crime and drug use. She’s open, funny, and warm, but with the edge of someone who, when they were younger, was probably a wild child and heaps of trouble. And during the pandemic, she says, she stole money from the state and federal government.

When the pandemic hit, she went right to work: following her local elected officials online for info, and applying for unemployment and rental assistance as soon as it was offered. She says it helped that she moved fast and got in early. She used stolen identities acquired from street connections to apply for more and more unemployment relief from the feds. She claims to have made tens of thousands of dollars; sending out as many as 40 to 50 requests using different IDs, getting a handful of hits for every batch of claims she sent in. She hid the scheme from her kids, but says that “they still think of me as a bank.”

She knows people in her neighborhood who needed help but wouldn’t take money from the feds because they were so suspicious of the government. “They just couldn’t believe it,” she says. “They thought the government would take it all back or fuck with them in some way.”

She didn’t go for huge sums and was satisfied with not getting too crazy and attracting attention. Still, she says, she’d never seen so much cash in her life, and feels like she was due. “It’s reparations!” Danni tells me. “We don’t have money. And if the government hadn’t given out that money, well, then the people would have come to the nicer neighborhoods and taken it.”

Given how things boiled over in America that summer of 2020, she has a point.

Danni comes by all this, well, honestly. She was born into this life. Her mom liked pills, and her dad was a no-show. So she was raised by relatives with connections to the underworld. Her brothers have all done time. (“I don’t speak to one of them. Saw him at the gym the other day, and we just walked on by each other,” she says and laughs, but it feels a little wistful.) As a teen, she got locked up, too, and bounced around after jail, always hustling. She’s seen shit. Her partner dealt drugs and was gunned down in front of their kids. And when the pandemic hit, she knew just what Jason Kane knew hundreds of miles away: There was a way to get paid, and folks with a certain mentality would find that way.

She rolls her eyes and laughs when I ask her about Nuke Bizzle’s case (“What an idiot!”) and says she knew when to call it all off. After years of running all kinds of grifts that she’d prefer not to elaborate on, she has a sense for these things. “I call it living off the land,” she says. “I didn’t get greedy. That’s how you get caught. I kept it low risk. But I was going to get mine. I lived it up: hotels, trips — flying was cheap during the pandemic.” She was out at clubs most nights. “I didn’t get Covid until my kids went back to school.”

She doesn’t really consider what all this meant to the people whose IDs she had stolen. She did take note of some medical bills that arrived for one of her stolen identities but mostly just shrugs. All the hassles, headaches, and stress folks like the Clarks will face? Not her problem.

While the Secret Service efforts have been effective — Kane estimates they have seized or prevented more than $2 billion in pandemic-era fraud — the officers know that so much more was stolen. “What keeps me up at night is the amount of money that we lost,” he says. “We could only act as fast as we could act. Our people worked countless, countless hours to return funds, but it wasn’t enough. I can handle 500 cases, maybe 1,000. I can’t handle 10,000 cases as an agency.”

They are still working pandemic fraud cases, but the agents admit that they are down to a “trickle.” They, like every organization, have to prioritize, and they are facing an influx of romance scams, sextortion, and a nasty scheme called “pig butchering,” where the mark gets fattened up with phony investment returns only to be cleaned out. There’s the Black Ax gang in Nigeria on the rise, the Double Dragon crew out of China, and a new rash of electronic-bank-transfer thievery among all kinds of threats they have to try and enforce. Their work is never ending.

“The victim gets lost in this,” Kane says. “In Covid fraud, it’s usually the government that ends up paying. But at the end of the day, Americans are the victim, because it’s all taxpayer money.”

Talcove agrees — and believes the small-scale damage done by lone-wolf grifters like Danni pale in comparison with organized criminal outfits hitting America with bigger scores. He’s been warning whoever will listen that criminal organizations see Uncle Sam as the biggest mark in the world and that this could all easily happen again — and it in fact has. This year, a Romanian gang allegedly stole more than $38 million from Los Angeles’ poorest citizens by engaging in EBT fraud, using a scheme that worked much like the unemployment scam of the pandemic.

“I’ve got a cynical view on this,” Talcove admits. “I don’t really think politicians give a shit about the people in need because if they really cared, they would do what they need to do.”

Talcove has a list of solutions, most in line with the Biden administration, some not much more complicated than authentication protocols much like what your bank or credit card would ask for and better communication between the feds and states. “The challenge right now is that government agencies have little incentive to acknowledge a fraud problem as it creates an issue with their oversight committee and the press,” Talcove says. “We need a mechanism to ensure controls are in place to stop these groups from stealing while at the same time ensuring people can access the needed systems. The only way to solve this problem is information and analytics. The bad guys have information and analytics. If we don’t have information and analytics, we are screwed.”

For her part, Danni’s gone back to her usual side hustles, but the next time there’s a crisis, she’s got a playbook. And if the government isn’t prepared, if Biden and the House haven’t acted and instituted some real safeguards, well, she’ll hit them up all over again. It’s fast becoming the American way.

More from Rolling Stone

Sam Pollard Considers 'The League' More Than a Baseball Documentary

Who's Giving HBO's 'The Idol' All of These Five-Star Ratings?

Best of Rolling Stone