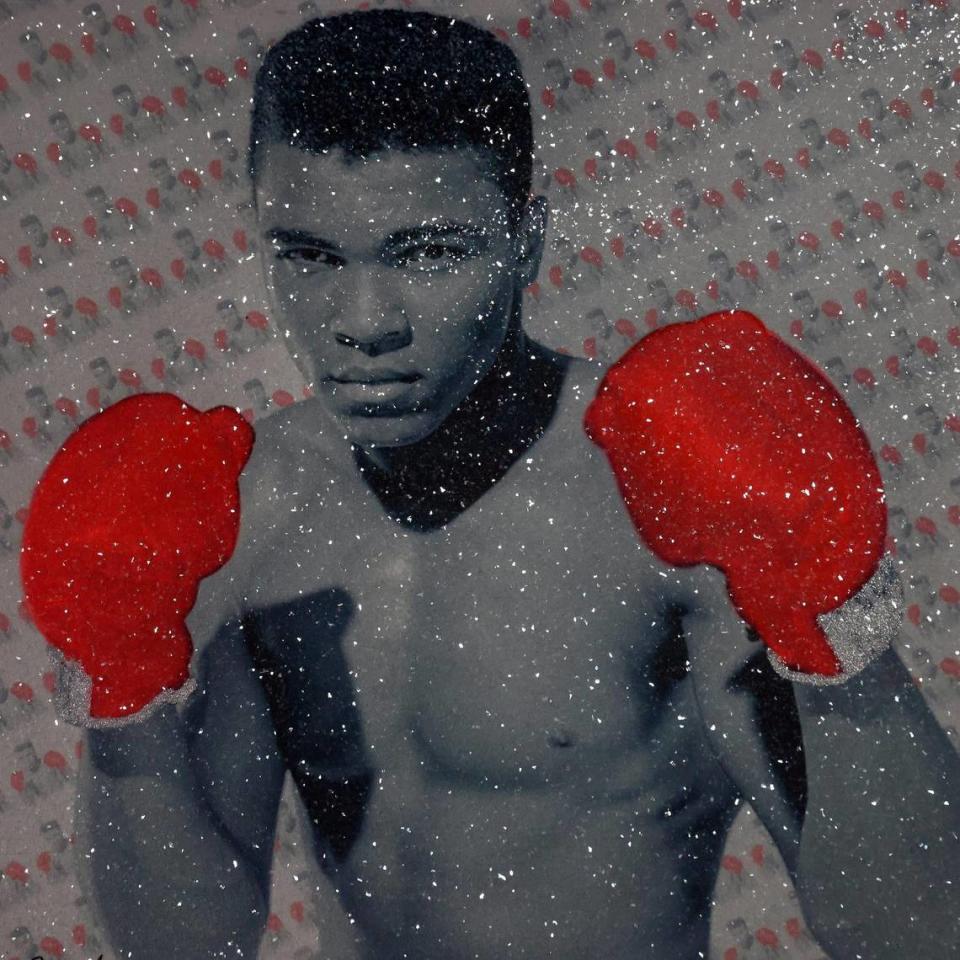

The triumph and transformation of Muhammad Ali is celebrated in this Miami exhibit

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As a kid growing up in Seattle in the 1970s, Troy Wright idolized Muhammad Ali. He had the showmanship. He had the athleticism. And most importantly, he had the commitment – to his beliefs, to his people and to equality.

“What he represented changed the mindset of everybody,” Wright said, “because there were people who were where I was from who said, ‘You know what he’s right. You can’t just discriminate [against] me because of my color.’”

Now the executive director of Miami Beach’s Washington Avenue Business Improvement District, Wright helped organize “I Shook Up the World,” an exhibit at the current Fifth Street Gym (the original location where Ali trained was torn down in 1993) on South Beach. The exhibit commemorates the 60th anniversary of then-Cassius Clay’s victory over heavily favored heavyweight champion Sonny Liston.

A collaboration between the Washington Avenue BID and HistoryMiami, the exhibit will explore how the title fight and Ali’s time in Miami shaped the rest of his life. Through pictures and memorabilia, visitors will get a glimpse of not only his upbringing but the significant role that Miami played in helping Ali emerge from the Clay cocoon.

“It was kind of a wake-up call for him,” Jonathan Eig, the author of The New York Times bestseller “Ali: A Life” said of the former heavyweight champion’s time in Miami. “He’s learning that there’s a different segregation outside of Louisville. That Miami is a not exactly a southern city but it is in someways. And he’s beginning to explore the Nation of Islam.”

Although segregation might have looked different in South Florida, it likely still felt the same when then-18-year-old Clay came to Miami in late 1960 to train under Angelo Dundee, the owner of the Fifth Street Gym. He couldn’t stay in Miami Beach. He couldn’t jog over the MacArthur Causeway without sometimes being stopped by police. He couldn’t even try on a dress shirt at Burdine’s.

“I told the manager, ‘This man won an Olympic gold medal for his country,’ “ photographer Flip Schulke, who was with Clay at Burdine’s, told the Miami Herald in 2004. “Cassius didn’t want to argue. He just wanted to leave.”

In Miami, Clay also found a civil rights movement that was well underway.

“The civil rights period in Dade County predated the civil rights period in other parts of the South by at least a decade,” historian Marvin Dunn wrote in his seminal text “Black Miami in the Twentieth Century.” As early as the 1940s, Black Miamians such as Father John Culmer, G.E. Graves Jr. and M. Athalie Range had been challenging Jim Crow laws.

Clay also wanted to find his role in the fight for equality.

“There were many ways for people to participate in the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s,” he wrote in his autobiography, “The Soul of the Butterfly.” “… I chose to join the Nation of Islam, which promoted Black pride and independence. When I became a member, I was fighting for equality and Black pride at the same time. Whatever approach you chose, the goal was the same: We all wanted freedom, justice, and equality for Black people in America.”

Clay first discovered the group as a high-schooler in 1959. Shortly after his arrival in Miami, he attended his first service at the then-storefront Mosque No. 29. Clay later struck up a friendship with Malcolm X, who caused quite a stir when he visited Miami in the days leading up to the Liston fight after the two met in 1962. Their relationship deepened Clay’s commitment to Islam.

“Ali was learning from Malcolm how to be a man, how to be an activist, how to fight for Black dignity,” Eig said. “I think Malcolm wanted Ali to see the power that he had, that this thing brought an opportunity for influence.”

‘I’m free to be what I want’

It’s clear that Malcolm’s words stuck.

“When you saw me in the boxing ring fighting, it wasn’t just so I could beat my opponent,” Ali reflected in “The Soul of a Butterfly.” “My fighting had a purpose. I had to be successful in order to get people to listen to the things I had to say. I was fighting to win the world heavyweight title so I could go out in the streets and speak my mind.”

It’s not like Clay hadn’t spoken his mind before. The incessant trash talk and taunting of Liston made the young boxer a fan favorite. What he wanted, however, was for people to listen , something that would only be accomplished with a heavyweight belt around his waist. And though he projected domination – the man even released a spoken-word album entitled “I Am the Greatest” in 1963 – the odds still favored Liston 7-1.

“We didn’t know we were gonna win, we didn’t even think of the significance,” Clay’s cornerman, Ferdie Pacheco, told the Herald in 2014. “There was sheer terror Liston was going to kill us! It was a huge surprise.”

Added Eig: “Some of his close friends thought that he really was panicking. Even his trainers thought that he was having a panic attack at the weigh-in.”

Although Clay would shock the world by besting Liston in seven rounds on Feb. 25, 1964, it was the following days and years that cemented his legacy as not just one of the best boxers of all time but arguably the most influential athlete ever. The day after the fight, he officially announced his conversion to the Nation of Islam.

“I don’t have to be what you want me to be. I’m free to be what I want,” he said. “I believe Allah is God. I think this is the true way to save the world, which is on fire with hate.”

By March 6, Elijah Muhammad had given Clay the name Muhammad Ali. Less than two years later, he would refuse to be drafted into the Vietnam War, uttering the famous words, “No Viet Cong ever called me n-----.”

For young people across the country, many of whom were disillusioned with the American experiment following the bloody deaths of John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, Ali had turned into a symbol of resistance.

“He’s embraced by a lot of young people who were counter culture or who were against the establishment,” HistoryMiami resident historian Paul George said. “He becomes this guy who was not only probably the greatest athlete in the world at the time but this incredibly polarizing figure.”

And while Ali was vilified by the white media for his audacity to question the status quo, the little Black kid growing up in Seattle still loved him — so much so that when a young Wright heard that his hero was in town, he spent more than three hours searching for him.

“I am what he fought for,” Wright said. “If it were not for him, I would not be here. Yes, I might be the only brother down here on Miami Beach but what that’s telling me is I have to set the same example Muhammad Ali did.”

Wright beamed with pride as he discussed the importance of the exhibit – especially considering the history of Miami Beach. To him, Ali represented patriotism.

“He was the full expression of what it means to have the liberty of free speech,” Wright said.

IF YOU GO

WHAT: “I Shook Up the World” Exhibit

WHEN: noon-10 p.m. Feb. 23-April 1

WHERE: 555 Washington Ave., Miami Beach

TICKETS: $15 (students), $25

Info: www.eventbrite.com/e/muhammad-ali-historical-timeline-tickets-796986828057?aff=oddtdtcreator