The Right to Troll: Supreme Court to Hear School Board Social Media Case

Social media, the Supreme Court said in 2017, is “the modern public square.” For parents, it’s often the easiest way to engage with officials who run their children’s schools.

On Tuesday, the court will consider whether those officials — in one case, board members for the San Diego-area Poway school district — can block constituents from responding to posts on platforms like Facebook and X.

“Government accountability … goes down the toilet if officials can effectively ‘mute’ their critics,” said Cory Briggs, an attorney who represents Poway parents Christopher and Kimberly Garnier. “Nobody is required to read the comments on social, but preventing them from being expressed in the first place ensures that nobody ever hears dissenting voices.”

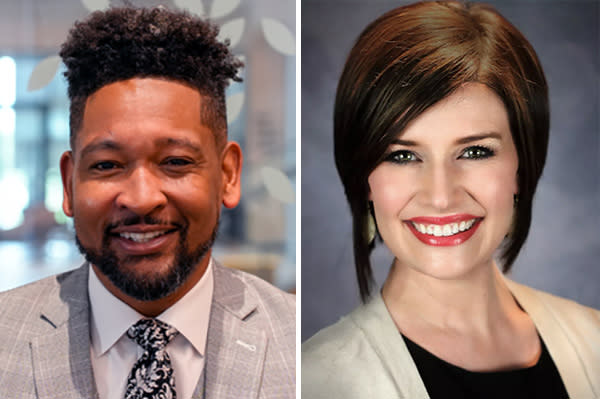

Michelle O’Connor-Ratcliff, a current board member, and T.J. Zane, who served from 2014 to 2022, argue that they were acting as private citizens and, therefore, had a right to cut off the Garniers’ ability to reply. They complained that the couple essentially trolled them, repeatedly posting the same comments — in one instance, more than 200 times in a 10-minute period — and cluttered up their feeds.

But the Garniers say both O’Connor-Ratcliff and Zane identified themselves as government officials and that, by all appearances, used social media as an extension of their board positions. Blocking them — no matter how annoying or off topic their posts might have been — was a violation of free speech and their First Amendment right to petition their government, according to their lawsuit. The U.S. Appeals Court for the 9th Circuit agreed.

In an age when the public is far more likely to air concerns about government online than attend an official meeting, the case has major implications not just for how parents engage with school board members, but for how citizens in general interact with their elected leaders. It’s one of two cases before the court on Tuesday that pose the same question — whether an official’s use of a private social media account amounts to “state action.”

The second involves a city manager in Port Huron, Michigan, who blocked a resident after he complained about local efforts to prevent COVID transmission. In that case, the federal appeals court took the opposite view, saying the manager did not act “under the color of law.” The split between the lower courts prompted the Supreme Court to take up the cases.

Like the Garniers, some First Amendment experts want the court to uphold the 9th Circuit’s decision. Katie Fallow, senior counsel at the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, said if an official discusses government business on social media, the First Amendment still applies, even if using the account isn’t a formal part of the job.

Ryan Walters: How a Beloved Teacher Became Oklahoma’s Top Culture Warrior

“They use it to talk to the public about their policies and solicit input from constituents,” she said. “The question is, ‘Does the public consider this to be the source of official pronouncements?’ ”

Fallow has experience with the issue. The Knight Institute sued former President Donald Trump in 2017 because he blocked critics on Twitter. The Institute won the case at the appellate level, but the Supreme Court dismissed it because Twitter’s former owners suspended his account in 2021 following the uprising at the U.S. Capitol. (Trump’s account has since been reinstated.)

O’Connor-Ratcliff and Zane — like Trump — opened their accounts before they took public office. “Once elected, they keep using it,” Fallow said. “They want their brand and their followers.”

Neither O’Connor-Ratcliff, Zane, nor their attorney agreed to an interview prior to oral arguments, but representatives for other elected officials have been closely following both cases.

The California School Boards Association wrote in a brief to the court that if the Garniers win, boards would have to “police” members’ social media accounts and could potentially face more litigation . During elections, the association added, incumbents would be limited in controlling unflattering posts while challengers would be free to restrict negative comments.

Board members need a “practical test” that clarifies “when social media activity transforms from personal to state action,” the association wrote. Because of the “rapidly evolving nature” of social media, the rules should apply across all current and future platforms, the brief said.

The Biden administration filed a brief in the case because “federal government officials also use social media accounts,” and whatever the court decides would apply to those officials and employees.

Years of conflict

The Garniers, who have three children in the district , have a troubled relationship with Poway officials that goes beyond social media posts. In 2013, Christopher, who once worked as a coach in Poway schools, filed a wrongful termination lawsuit against the district. Then in 2015, a judge granted the district a restraining order against him requiring that he stay away from his children’s school and its former principal. He was accused of making verbal threats, disrupting a meeting and pounding on car windows — allegations he denied.

Christopher, who is Black, argues that he was singled out because of his race and that the district treats minority students unfairly. It’s an issue that surfaced in comments his wife posted on the board members’ Facebook pages. According to court documents, Kimberly posted: “I have children of color in the district, and I don’t want them going to school and seeing a noose.”

Christopher’s replies focused on both racial and financial matters. Following several of O’Connor-Ratcliff’s posts, he wrote that the board members, among other officials, “refuse to meet with our interracial family.” In another lengthy Facebook reply, posted multiple times, Christopher argued that Black students in the predominantly white district were disproportionately suspended and that he didn’t receive all the discipline data he requested through a public records request.

He was an outspoken critic of former Superintendent John Collins, who pleaded guilty in 2017 to not reporting more than $300,000 in consultant income, a misdemeanor. Collins was sentenced to five years probation and had to repay the district $185,000.

“Trustees lack the intestinal fortitude to fire this man,” Christopher replied in response to several posts from 2015. Briggs, the Garniers’ attorney, said his clients thought financial oversight had not improved since the board fired Collins in 2016.

“How many times should constituents be allowed to express admittedly legit criticism of their elected representative’s performance?” Briggs asked. “The answer can only be: as many as it takes to get [them] to do better or to get [them] voted out of office.”

‘Strange bedfellows’

The case predates the pandemic. But the COVID era — with its virtual government meetings and restrictions on in-person gatherings — has only intensified the level of vitriol on social media.

Data shows that Americans who rely on social media for news tend to be younger and more likely to have school-age children. Forty percent were in the 30-49 age range, according to a 2020 Pew Research Center poll. Online threats of violence against public officials, meanwhile, have increased, data shows, especially toward judges and prosecutors. But at the height of debates over mask mandates and vaccines, superintendents and school board members were also targets of online intimidation and bullying.

Jonathan Zachreson of Roseville City, California, has been on both sides of the issue. During the pandemic, he advocated for reopening schools and against a vaccine mandate for students. State Sen. Richard Pan, who wanted to limit vaccine exemptions for students, even blocked him on Twitter (now X).

Now Zachreson is on his town’s school board. After he was elected, he said the district advised members on the legal issues surrounding social media. To him, there’s no gray area.

“Either don’t talk about school business or don’t block people — it’s like one or the other,” he said.

But he added that as with public meetings, there should be limits on “disorderly” behavior, like spamming. The question, he said, is whether the Supreme Court will draw that line.

Supreme Court Blocks Biden Workplace Vaccine Mandate: 'Significant Encroachment'

Andrew McNulty, a Denver attorney, said he can’t predict how the court — with a 6-3 conservative majority — will rule on the cases. He’s particularly interested because he represents a Denver Public School parent who filed a lawsuit last month against a board member who blocked her on Facebook.

“There’s so much conservative backlash about censoring speech,” McNulty said. The court has also agreed to hear cases from Texas and Florida on whether tech companies can be sued or penalized if they block or limit content. And it will consider a 5th Circuit case in which Missouri and Louisiana accused the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of conspiring with social media companies to suppress opposition to COVID vaccines, mask mandates and school closures.

Until now, the lawsuit against Trump was the most high-profile case over the issue. But Democrats have also been sued for blocking critics. In 2019, progressive New York Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez settled a lawsuit with a former Republican state lawmaker and talk show host she blocked on Twitter.

“The First Amendment makes strange bedfellows,” McNulty said. “It crosses the ideological spectrum.”