True in theory

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In the hours after gunshots cracked across Dealey Plaza on Nov. 22, 1963, Americans found themselves playing a novel role in a fast-paced drama. Within just six minutes, they heard over national radio that the president’s motorcade had come under fire. Four more, and Walter Cronkite told the CBS television audience that President John F. Kennedy Jr. had been hit. Another 58 minutes, and millions gathered around televisions heard Cronkite’s emotional announcement that the president was dead. Stunned viewers still remember that moment, but the search for answers was just beginning.

For four days, the networks suspended regular programming and even ads, so JFK’s death was the only thing on TV. Obsessed viewers followed along as police rounded up suspects, including a former Marine sharpshooter arrested at the Texas Theatre. Lee Harvey Oswald was among those “being grilled,” Cronkite reported sometime after 2 p.m., perhaps as a new president was being sworn in on Air Force One. Less than 12 hours after the shooting, Oswald was charged and paraded before a pool of cameras. When a reporter asked about his battered eye, the man leaned closer, his face filling the nearest camera. “A cop hit me,” he said, flatly.

Never before had such grand and mysterious events played out at this speed. Then came a plot twist: A nightclub owner named Jack Ruby shot Oswald dead on live television in a crowd of police escorting the suspected assassin to jail. The nation reeled, trying to make sense of this improbable sequence. It was no longer just difficult to process, but hard for many to believe.

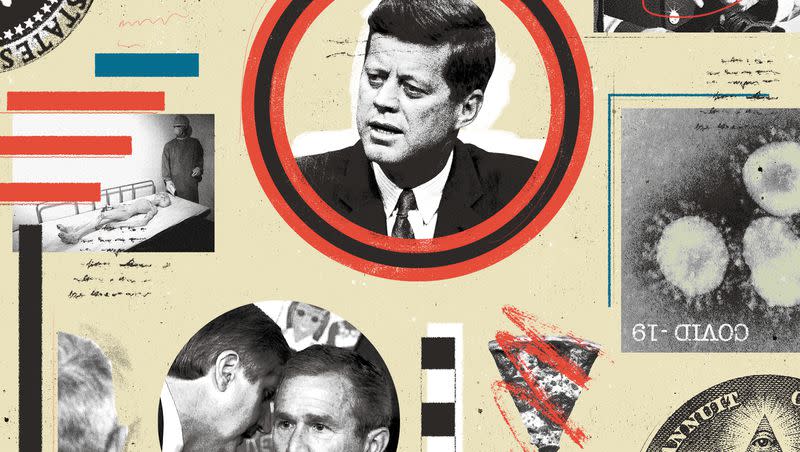

That remains the case 60 years later, when only a third of Americans believe that Oswald shot Kennedy and acted alone, the official conclusion reached by the Warren Commission, the federal investigation into his death. Many are familiar with alternative theories, or at least familiar elements, like the grassy knoll or the Zapruder film. This is largely because the case spawned a new subculture, a cottage industry of self-published skeptics and the audience they encourage to “do your own research.” As their work has expanded to new arenas — like the Apollo moon landing or 9/11 — their stories have moved from photocopied zines to social media, cinema and even mainstream politics. In an age of almost unlimited access to information, why are conspiracy theories such a powerful force?

Online chatrooms and social media offer new vectors where conspiracism can move faster than ever. And as people lose trust in traditional news sources, they seem more likely to find answers somewhere else.

Colloquially, the term conspiracy theory has become a pejorative shorthand for all manner of outlandish beliefs or ideas the speaker wishes to dismiss as zany or off-kilter. “Defining it based on what the words say, a conspiracy theory would seem to be any theory that involves two or more people working in secret to bring about some ends,” says Brian Keeley, a leading philosopher working in this space, though conspiracists tend to focus on powerful actors like government agencies or even celebrities. Such things can occur, but the broader application of these theories seems to arise from a human need to find meaning in cataclysmic events.

Conspiracy theories have emerged throughout history and all over the world, often in the aftermath of crisis situations. When Rome burned in A.D. 64, some speculated that it was an inside job, ignited so Nero could rebuild the city with a clean slate. Medieval Europeans repeatedly accused Jewish communities of orchestrating epidemics like the plague; this proved a useful out for nobles indebted to Jewish merchants. Similarly, King Philip IV of France leveraged salacious rumors of his own creation in the 14th century to remove the Knights Templar from powerful roles in his own government, spawning theories that persist today.

Like Philip, other state actors have advanced conspiracy theories as a type of disinformation — the deliberate use of false or inaccurate information to undermine foreign governments or political opponents. When Tsar Nicholas II came under fire for mismanaging the Russian empire in the early 1900s, his secret police forged the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” purportedly minutes from the first Zionist congress of 1897, but in reality based on works of fiction. Likely intended to shift blame and conjure up a unifying threat, this document continues to underlie antisemitic theories about the banking system and the “new world order.” Russian intelligence services are still known to use similar methods.

But Americans have a unique relationship with conspiracy theories. Suspicions surrounding the British crown helped to fuel the independence movement, forming a template for subsequent anti-government theories. Americans were not exempt from bigoted beliefs about their neighbors, particularly Catholics, Jews and Latter-day Saints. But as the country marched west, the nation’s capital became an increasingly distant and misunderstood center of power. Scandals like Teapot Dome and Watergate haven’t exactly bolstered trust. Even President Dwight D. Eisenhower weighed in during his farewell address in January 1961, warning against the “military-industrial complex.”

This was the state of affairs when JFK was killed. American society offered fertile soil for conspiracy theories to take root and grow, empowered by technologies like radio and TV, with more innovations coming. This new conspiracist subculture would become an arena for the arts to explore, sometimes with a tinge of romance, but more often with disdain. Either way, film, literature and popular music would help introduce their ideas into mainstream thinking.

“There’s a puzzle out there, there’s a mystery. There’s an unsolved crime. And you think, ‘Well, if I looked at all of the evidence, I could figure it out.’”

Jim Garrison was no amateur. Something of a loose cannon, the New Orleans district attorney had cracked down on the city’s French Quarter vice in 1962 and charged his own supervisors with racketeering. But when he started pursuing tips that a local plot led to JFK’s death, he soon believed he was unraveling a web of relationships and chatter that denoted a grand conspiracy. In 1969, he brought one defendant to trial, the only case ever heard in relation to the president’s murder. Jurors deliberated all of 54 minutes before returning a verdict: not guilty. Critics gloated, calling Garrison a “total charlatan,” his investigation a reckless and cruel publicity stunt. But he wasn’t finished, and Americans weren’t satisfied.

Officially, the case was closed in September 1964. That’s when the President’s Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy — the Warren Commission — issued its 888-page report, finding that both Oswald and Ruby acted alone. It was closed again in 1988, even after the House Select Committee on Assassinations argued that unnamed conspirators had probably played a role. The Justice Department responded that “no persuasive evidence can be identified to support the theory of a conspiracy.” But some preferred unofficial answers.

The first published alternative beat the Warren report by four months — at least in Paris, where author Thomas G. Buchanan was based. The New York Times called his book “Who Killed Kennedy?” an “elaborate concoction,” alleging a plot to protect the oil and defense industries, using police and criminals as stooges, with Oswald a CIA agent, all presented without evidence. Still, the reviewer concluded, the hypothesis “can be expected to provide sinew and tissue for the Kennedy legend, which will continue to attract men’s imaginations for decades to come.”

The Times wasn’t wrong. Another book, “Rush to Judgment,” spent over seven months on the bestsellers list in 1966-67, perhaps inspiring would-be authors. Among them, the author of 1975’s “The Umbrella Man” called himself an “assassinologist.” A noted Garrison critic authored 1981’s “Best Evidence”; and Garrison added his own memoir, “On the Trail of Assassins,” in 1988. That same year, novelist Don DeLillo released “Libra,” portraying Oswald as a pawn in a CIA scheme to start a war with Cuba. In 1995, James Ellroy threw the mafia into the mix with “American Tabloid,” while Norman Mailer explored the alleged shooter’s formative period in Russia through newly released KGB materials in “Oswald’s Tale.”

The list goes on, with documentaries and podcasts for good measure. One reason for so many theories is that Kennedy had many enemies. His initial backing of the Bay of Pigs invasion and subsequent about-face irked Cuba, the CIA and anti-Castro Cubans living stateside. His second thoughts about Vietnam were an affront to the military and defense contractors. His brother Robert’s pursuit of the mafia as attorney general didn’t make him any friends there. So one can pick and choose. “If you’re conservative, you can believe the Soviets or Fidel Castro of Cuba killed Kennedy,” says University of California, Davis historian Kathryn Olmsted. “If you’re liberal, you can think it was the military industrial complex that killed Kennedy because he wanted to get out of the Vietnam War.”

This has practically become a field of study, embodied by a 2018 exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City titled “Everything is Connected: Art and Conspiracy.” Visitors grappled with decades of “suspicion between the government and its citizens” through 70 works produced between the 1960s through 2016. Some used government reports and statistics to reveal real corruption, while others dove “headlong into the fever dreams of the disaffected.” The museum called it “an archaeology of our troubled times.”

“People start to believe that everything is an illusion, that everything is a sham. You can’t trust anyone. You can’t trust governmental authorities. You can’t trust educational authorities. You can’t trust scientific authorities.”

Controversial filmmaker Oliver Stone wasn’t impressed with Garrison’s work. “He trusted a lot of weirdos and followed a lot of fake leads,” he admitted later. But in Garrison’s book, the basis for his 1991 blockbuster, “JFK,” he found a compelling story of a man struggling to piece together his own truth. Unlike Stone’s oeuvre of anti-war films, “JFK” is less a leftist screed than an oddly sympathetic profile of a conspiracy theorist, played by Kevin Costner. Reminiscing later, Stone said that the official story of the assassination was “a great myth,” and that “in order to fight a myth, maybe you have to create another one.”

A hero typically overcomes adversity to achieve an honorable goal, like finding treasure or saving the world. Those elements are present in conspiracy theories, but the person is not. Or perhaps the hero is implied. The character facing long odds to solve a mystery is the theorist himself. This seems to be one lure of conspiracism. “There’s a puzzle out there, there’s a mystery,” Olmsted says. “There’s an unsolved crime. And you think, ‘Well, if I looked at all of the evidence, I could figure it out.’” This mindset can imbue ordinary life with false drama and significance.

Bad actors can use that to their advantage, and not just spies or heads of state. “We’ve got to not forget the capitalism part of conspiracy thinking,” says University of Utah historian Robert Goldberg. Operating outside of traditional institutions and expertise, the “conspiracy entrepreneur” may or may not believe his theories, but he profits from them, through his writings or selling merchandise like T-shirts emblazoned with silly slogans like “Bush did 9/11.” But what he really sells is reassurance in uncertain times: This did happen for a reason. Even if that reason is clearly delusional.

This is where it gets dangerous. If conspiracism seems to borrow the language of religion, it may not be coincidental. For the most obsessed and confused, these theories can become an alternate belief system, driving them to take action. In “Waco: The Aftermath,” now streaming on Showtime, an FBI special agent executing a search warrant on a neo-Nazi safehouse finds a battery of fax machines, all beeping at once. Each machine is sending a copy of an anti-government conspiracist newsletter, inspired in part by botched and deadly government sieges at Waco and Ruby Ridge. In this show’s myth, these electronic devices take resentment viral, contributing to the Oklahoma City bombing.

The internet is like an infinite number of fax machines, selling any number of myths. We know that conspiracy theories operate like a memetic virus: The more people believe them, the more they spread. Online chatrooms and social media offer new vectors where conspiracism can move faster than ever. And as people lose trust in traditional news sources, they seem more likely to find answers somewhere else. Even political candidates on both sides of the aisle have fallen into this trap, or used it to their advantage. The end result is a climate where the line between truth and fiction becomes more difficult to find.

“People start to believe that everything is an illusion, that everything is a sham,” Olmsted says. “You can’t trust anyone. You can’t trust governmental authorities. You can’t trust educational authorities. You can’t trust scientific authorities. You have to ‘do your own research’ and come to your own conclusions. And that means that you’re susceptible to believing any lie that public figures put forward that fit your biases.”

Still, amid the plethora of conspiracy theories circulating today — like flat earth theory, QAnon, or unidentified aerial phenomena — the JFK assassination looms large. Last spring, the federal government began to release a trove of related documents. And in September, a former Secret Service member who was present when Kennedy was shot shared certain details with The New York Times that could rewrite prevailing theories. But perhaps rather than fixate on his death, we could learn something from his life. As he once said, “the great enemy of truth is very often not the lie — deliberate, contrived and dishonest — but the myth — persistent, persuasive and unrealistic.”

This story appears in the November issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.