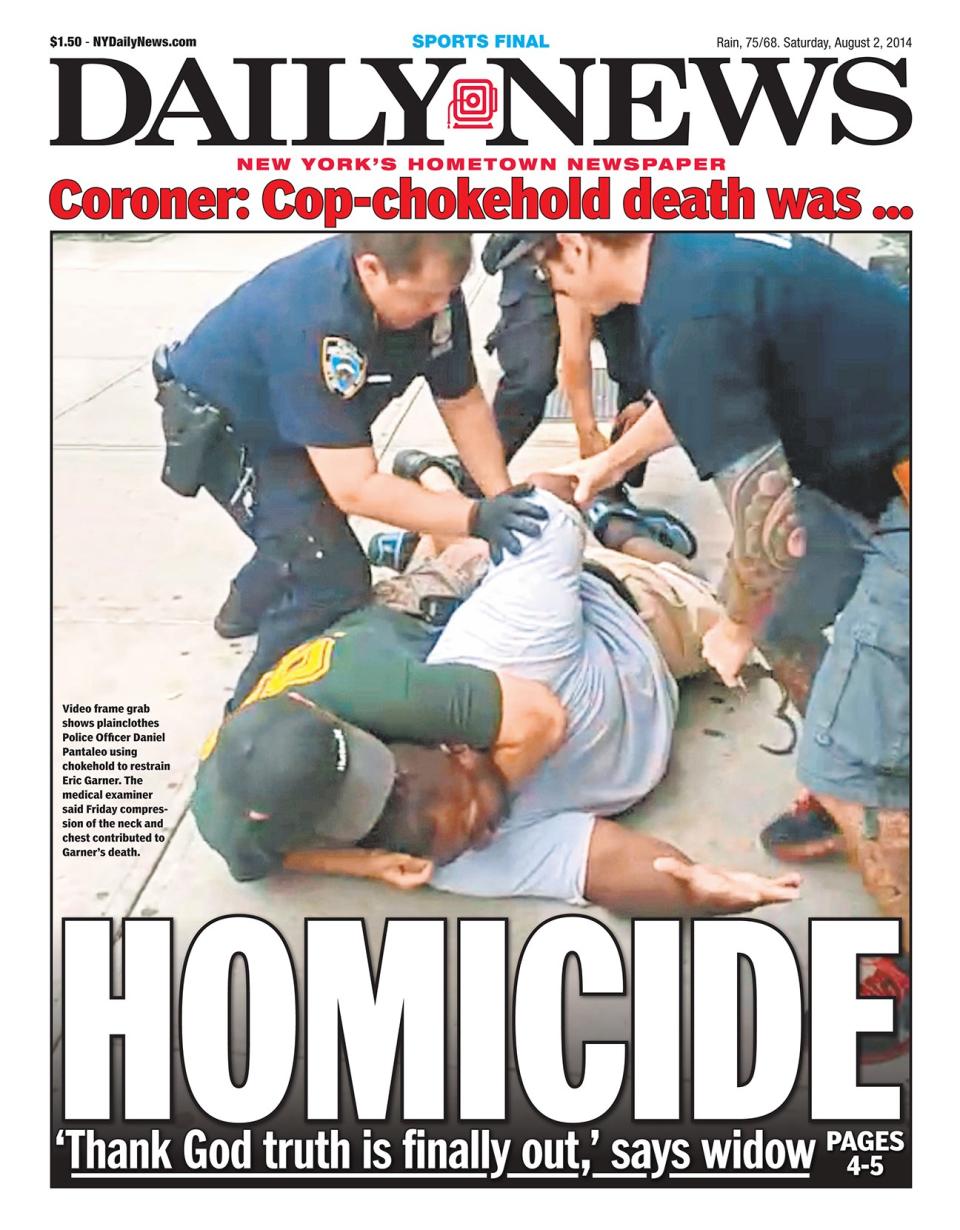

The Trump Administration Decided Not to Prosecute the Officer Who Killed Eric Garner

On Tuesday, federal prosecutors announced that they would not bring any charges in the death of Eric Garner, an unarmed 43-year-old black man killed by a New York City Police Department officer during a 2014 arrest. In doing so, the Department of Justice expressly overruled the attorneys within its own Civil Rights Division, who after an extensive investigation recommended charging Daniel Pantaleo in connection with the chokehold he used to subdue Garner in front of a Staten Island beauty-supply store. According to ABC News, the decision to let Officer Pantaleo walk came directly from Trump attorney general William Barr.

Prosecuting state and local law enforcement officials for federal civil rights violations is a notoriously difficult task because of the high burden of proof in such cases: At trial, prosecutors must show that an officer intended to violate the victim's civil rights. If the officer was simply negligent (that is, they should have known the risks of their actions) or even reckless (that is, they knew the risks and chose to ignore them), it won't be enough. Federal prosecutors in New York had argued against charging Pantaleo, and a Staten Island grand jury declined to indict him. A 2016 Pittsburgh Tribune-Review analysis of nearly three million civil rights complaints over two decades found that the Justice Department declined to bring charges 96 percent of the time.

The Civil Rights Division believed Garner's case was different; Barr, apparently, did not. According to an unnamed senior DOJ official with whom ABC News spoke, once authorities determined they could not prove that Pantaleo possessed a "willful intent" to harm Garner, no other facts of the case—for example, the medical examiner's determination that Garner's death was a homicide, or the NYPD regulations prohibiting the chokehold Pantaleo used, or the eleven times Garner shouted, "I can't breathe" before losing consciousness—were relevant. The official also "acknowledged that the legal analysis surrounding Pantaleo's actions would have been different had he been a civilian." In other words, because Pantaleo killed Garner while on the clock, he bears no responsibility for the death he caused.

460150878

New York Daily NewsBarr's choice to ignore his Civil Rights Division's recommendation is consistent with the generous presumption of innocence the Trump administration extends to anyone wearing a badge. Less than a month into his tenure as Trump's first attorney general, Jeff Sessions dismissed moral outrage over police brutality—especially against black and brown people like Garner, Philando Castile, Walter Scott, and Laquan McDonald—as the unfortunate side effect of a spate of "viral videos." Under his leadership, Sessions promised, state attorneys general and federal prosecutors would rededicate themselves to fighting crime, not to suing law enforcement officers. (He never explained why these tasks are mutually exclusive.)

In August 2017, the Department of Justice rescinded Obama-era regulations, enacted in the aftermath of the Ferguson protests, that curtailed the availability of military-grade weapons to local police. Shortly before his resignation, Sessions imposed strict limitations on the circumstances in which DOJ officials can enter into future consent decrees—binding reform agreements that govern the use of force by law enforcement agencies accused of wrongdoing. He also criticized the Civil Rights Division's habit of investigating allegations of department-wide misconduct, and admitted that although he had not read the Division's reports—including one authored after McDonald's murder detailing the Chicago Police Department's mistreatment of minority suspects—he found them to be "pretty anecdotal" and "not so scientifically based."

Trump, meanwhile, has made voicing his enthusiastic support for law enforcement, often tinged with the racism and xenophobia that have animated his rise to power, into one of his most dependable applause lines. During the 2016 campaign, he decried the "relentless criticism " and "hostility against our police," especially in "inner cities," and proclaimed himself to be the race's "law and order candidate." In a 2017 speech, he blamed crime on a combination of "weak borders" and "weak policing," and excoriated laws "stacked against" officers that purportedly keep them from doing their jobs. He wrapped by encouraging audience members to be "rough" with individuals in their custody, and to not worry too much about covering heads when shoving people into the back of squad cars.

In the most extreme manifestations of this ethos, Trump has used the powers of his office to reward authority figures who have already been convicted of crimes—especially crimes committed against members of vulnerable groups. In May, he pardoned Michael Behenna, a former Army solider who murdered an Iraqi man during an interrogation in 2008. In August 2017, the president issued his first-ever pardon to former Maricopa County, Arizona, sheriff Joe Arpaio, who turned his jails into self-described "concentration camps" and oversaw what a Department of Justice expert called "the worst pattern of racial profiling by a law enforcement agency in U.S. history." To Trump, this made Arpaio a "patriot" who was treated "unbelievably unfairly," and he defended the pardon as "the right thing to do."

The difficulties associated with prosecuting federal civil rights cases against police officers predate Trump's time in the White House. But his administration's fondness for state-sanctioned violence exacerbates the impact of the biases inherent in the legal system. It decreases the already slim chances that perpetrators like Daniel Pantaleo are held to account, or that victims like Eric Garner obtain some measure of justice.

Originally Appeared on GQ