Trump claim breaks with custom: Presidents alone don't usually declassify documents

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

WASHINGTON – After the military raid that killed Osama bin Laden, President Barack Obama sought to briskly release information as soon as the Al Qaeda leader was confirmed dead May 2, 2011.

But Obama's late-night announcement was carefully crafted, included a spare description of the operation and "didn't get into other classified elements of the mission and how it was set up," Leon Panetta, then head of the CIA, told USA TODAY, explaining the meticulous process used to not reveal confidential government information.

Obama's consultation with intelligence agencies to determine what intelligence to release publicly contrasts sharply with Donald Trump's assertion that as president he could declassify documents merely by thinking about it – a claim he made after FBI agents seized about 100 classified documents from his Mar-a-Lago estate in August.

Trump both single-handedly declassified documents and also deferred to the intelligence community to keep documents secret during his team. In 2019, he tweeted a previously classified satellite photo of an Iranian rocket mishap, which he said he had the "absolute right to do."

But in 2017 Trump postponed the release of some documents associated with President John F. Kennedy's assassination because of intelligence concerns. The slow release of information in both Trump and Obama administrations illustrates that despite their broad powers, it's rare for presidents to unilaterally declassify documents without input from intelligence agencies to determine what can be revealed and when. Declassifying documents can be long and deliberate, experts say, a far more intensive process than what Trump describes.

“This was not something driven by a seat-of-the pants response," Panetta said about the declassification review of the bin Laden raid. Some aspects of the raid remain secret more than a decade later, he added.

Trump news: Trump drops attorney-client claims over Mar-a-Lago documents

'Lives could be at stake': Trump document review to gauge whether US sources put at risk

Declassifying documents isn't simple for presidents

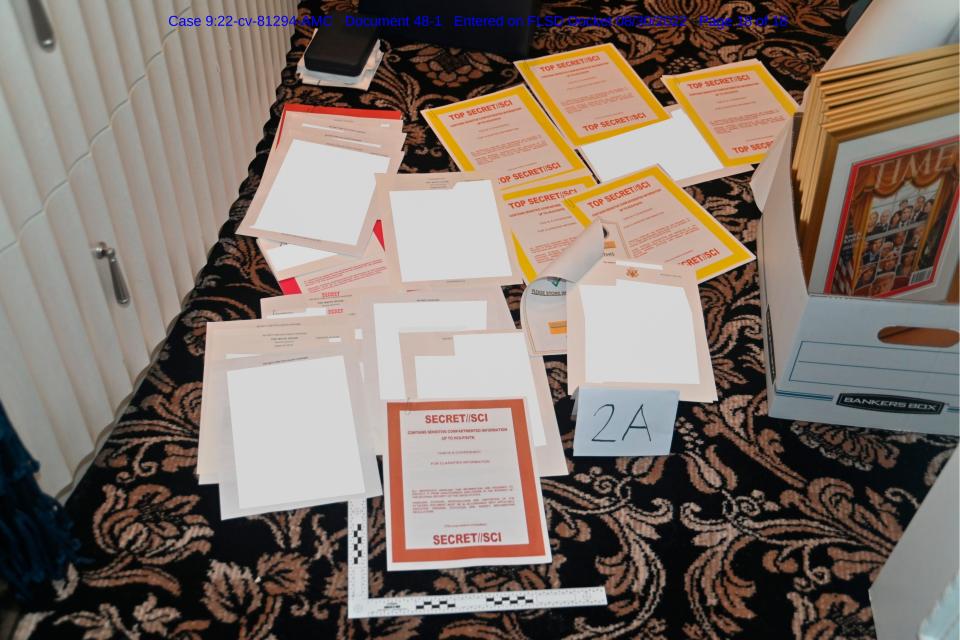

The seizure of top secret documents at Trump's Florida estate shined a spotlight on what role presidents play in declassifying the government's most sensitive records. Security experts said traditionally it's not as easy as a simple presidential declaration because intelligence officials need to ensure the sources and methods of gathering the information aren't revealed.

Trump claimed on social media and in interviews he declassified the documents at Mar-a-Lago while he was still president. "ALL documents have been previously declassified," Trump said in a statement Aug. 22.

But his lawyers haven't made that provocative claim in court as he fights a Justice Department investigation of the records. Government lawyers and national security experts treated Trump's claim with skepticism.

Declassification decisions – even when a president or Congress want the information released – are typically left for the agency that generated the document to review. The process can take months, years or decades.

Larry Pfeiffer, a former senior director of the White House Situation Room, told a panel at the Michael V. Hayden Center for Intelligence, Policy and International Security he had never heard during his 32-year intelligence career of a president personally declassifying something. The reason for agencies to review requests is to avoid revealing the people or technology that provided the information, where the risks can be life and death, he said.

“If there is a human asset involved, perhaps that human asset needs to be pulled out of the country and resettled somewhere," Pfeiffer said. "If there are technical assets involved, an assessment needs to be made as to the likelihood that that technical asset may now become neutered and unavailable to provide other additional information.”

How the US released information about Osama bin Laden's death

Information about the Navy SEAL raid led by the CIA to capture or kill bin Laden, the architect of the terrorist attacks Sept. 11, 2001, was one of the government's most closely guarded secrets – until it was over.

Rather than Obama single-handedly announcing the death, several steps were taken. Before the public announcement, Obama directed Panetta and Adm. Mike Mullen, then chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, to contact their counterparts in Pakistan because they hadn't been advised in advance.

Obama "wanted to be careful," Panetta said.

After more intelligence consultations, background briefings with reporters shed more light on the operation for the public in the following hours. Michael Morell, a 33-year veteran of the CIA, including two stints as acting CIA director, said a number of intelligence officials were asked to do a background briefing for the media on what led to the compound and on the military operation.

“There had to be considerations about how to do that and which facts would be revealed,” said John Fitzpatrick, who oversaw records access and information security management for the National Security Council during the last year of the Obama administration and the first two years of the Trump administration.

Congress later asked for more. The 2014 Intelligence Authorization Act required the Office of the Director of National Intelligence to conduct a declassification review of the materials collected during the mission. After "a rigorous interagency review," the office released three tranches of documents nicknamed "Bin Laden's Bookshelf" in 2015;, 2016 and 2017.

Despite the raid being described extensively in books, movies and other outlets, Panetta said some details remain secret.

"There always has been a clear understanding of how this information should be handled,” Panetta said. “I think it’s pretty clear that Trump had little regard for classified documents. I don’t think he has a clue of why the security of this information is important.”

Congress can also push a president to declassify

While presidents oversee declassification of executive-branch information, Congress occasionally asks to speed up the process.

Presidents provide guidance about how agencies declassify documents through executive orders, the most recent from Obama in 2009. That order calls for declassification of most records within 25 years – with exceptions to prevent revealing source identities or facilitating the development of weapons of mass destruction.

Congress occasionally requests faster declassification, which can lead to clashes between the lawmakers and executive intelligence agencies.

One example dealt with a Senate Intelligence Committee investigation of Al Qaeda terror suspects after the Sept. 11 attacks. The report found CIA personnel, aided by two outside contractors, initiated a program of indefinite secret detention of at least 119 people and coercive interrogations that in some cases amounted to torture. The chairwoman, Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., called the revelations "shocking."

The Senate panel voted twice to ask for an executive branch declassification review of the report before publicly releasing its 450-page executive summary – previously marked “top secret” and not for release to foreign nationals – in 2014. But the 6,700 page report remains under wraps.

Mary DeRosa, a former National Security Council legal adviser and now a professor of practice at Georgetown Law School, said after Obama made a decision to declassify legal memos about the program, there was lots of consultation among intelligence agencies. But not everyone agreed on the details of what could be released.

“When the president made a decision that was very much his, there was a process for it to make sure it was done correctly and recorded correctly,” DeRosa said.

Despite Republican and Democratic lawmakers denouncing the program's harsh methods, the full report remains classified. In 2016, Obama directed the report be preserved in the National Archives for 12 years before potentially being declassified.

The House and Senate intelligence committees can also trigger a five-day window for the president to object to a disclosure. Even when this strategy is invoked, the release of declassified material often takes longer than five days.

The House Intelligence Committee employed this strategy when it pressed for the declassification of its report about Russian interference in the 2016 election. Amid partisan bickering, a redacted version of the report was released in April 2018.

Intelligence experts said the review showed how the process works in even the most contentious circumstances.

“It’s an example of the folks around the president understanding that there is a set of rules that require consideration and consultation with the agencies and declassification happens this way,” said Fitzpatrick, who oversaw White House records access for the Obama and Trump administrations.

Trump followed protocols for JFK assassination records, not Mar-a-Lago

Trump has sometimes followed declassification rules and listened to the concerns of intelligence agencies – and ignored those customs at other times.

Trump said he had the “absolute right” to reveal the Iranian rocket picture. But releasing the remarkably crisp satellite picture alerted adversaries in Iran and other countries to U.S. surveillance capabilities.

“We had a photo and I released it, which I have the absolute right to do,” Trump told reporters Aug. 30, 2019.

After the Mar-a-Lago search, Trump said on Truth Social on Aug. 12 all the documents were declassified. He told Hannity on Sept. 21 a president “can declassify just by saying it’s declassified, even by thinking about it.”

The claim surprised former top officials in government. Panetta called the storage of classified documents at Mar-a-Lago "astounding." Former Attorney General Bill Barr said there was no justification for Trump to have classified documents at Mar-a-Lago. Justice Department officials have argued in court filings that no documentation exists to confirm records seized at Mar-a-Lago were declassified.

In contrast to the decisions about the satellite picture or Mar-a-Lago records, Trump followed tradition in dealing with documents about the Kennedy assassination.

A 1992 law called for the disclosure of all the government’s documents about the killing within 25 years. But the law allowed for postponements if agencies were worried the harm to military and intelligence communities “outweighs the public interest in disclosure.”

Trump was eager to release the records to squelch conspiracy theories when a deadline approached Oct. 26, 2017, for the release of another batch.

“Subject to the receipt of further information, I will be allowing, as President, the long blocked and classified JFK FILES to be opened,” Trump tweeted on Oct. 21, 2017.

But agencies appealed to Trump to delay the release for some undisclosed documents and he punted the disclosure to April 2018, then again to October 2021.

“After strict consultation with General Kelly, the CIA and other Agencies, I will be releasing ALL #JFKFiles other than the names and...addresses of any mentioned person who is still living," Trump tweeted a week later. "I am doing this for reasons of full disclosure, transparency and...in order to put any and all conspiracy theories to rest.”

The National Archives released thousands more documents in four installments in 2017. Another 18,731 documents were released after the six-month delay in April 2018.

Yet secrecy lingers nearly 60 years after the event Nov. 22, 1963.

Under President Joe Biden, the National Archives continues to review the redactions on 14,000 previously released documents in consultation with the departments of Defense, Justice and State, and the director of national intelligence. The latest deadline for another release is Dec. 15.

Contributing: Kevin Johnson

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Trump Mar-a-Lago documents: Presidents declassifying on own is rare