Before Trump, D.A. Fani Willis Targeted Teachers in Atlanta Cheating Scandal

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A decade before she unleashed the sprawling case now entangling former President Donald Trump in Georgia, Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis used similar methods to target an unlikely group: public school educators in Atlanta.

As an assistant district attorney in 2013, Willis turned heads in one of her first big cases: She helped convene a grand jury that indicted decorated Superintendent Beverly Hall and nearly three dozen other educators for cheating on state standardized tests. In the end, Willis brought a dozen cases to trial, with a jury convicting 11.

This week, Willis invoked the same statute — Georgia’s Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations, or RICO, Act — to indict Trump and 18 others in an alleged plot to overturn the state’s 2020 election results.

In doing so, she offered a reminder of her role in a divisive chapter in the city’s recent history. While the former president leveled accusations that Willis is, among other things, “a rabid partisan,” the cheating prosecutions left fissures in her own community, where many say she stood up for children but others accuse her of turning her back on Black educators.

‘Cooking the books’

Hall, the Atlanta superintendent, arrived in the district in 1999, eventually leading what she would call a data-driven turnaround. She told observers that under her tenure, Atlanta schools were “debunking the American algorithm that socio-economics predicts academic success,” The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported.

By 2009, her efforts had earned her one of education’s top honors: National Superintendent of the Year. But the same year, the Journal-Constitution published the first of several stories analyzing Atlanta’s results on the Georgia Criterion-Referenced Competency Test. The analysis found that scores had risen at rates that were statistically “all but impossible.” It also found that district officials disregarded internal irregularities and retaliated against whistleblowers.

Critics would soon compare Hall to “a Mafia boss who demanded fealty from subordinates while perpetrating a massive, self-serving fraud,” the city newspaper reported at the time. Willis pursued Hall using the same tools many prosecutors employ against Mafia bosses and drug kingpins. In bringing charges under the state’s RICO Act, Willis alleged that Hall and her colleagues used the “legitimate enterprise” of the school system to carry out an illegitimate act: cheating.

Lonnie King, a former head of the local NAACP, would later tell the newspaper that when he looked at the data, “I thought Beverly Hall was cooking the books” as early as 2006.

The newspaper’s coverage led Gov. Sonny Perdue to appoint a team of special investigators, who conducted 2,100 interviews and reviewed 800,000 documents. By 2011, they uncovered cheating in 44 of the 56 schools they examined, concluding that 178 educators participated. Investigators eventually found widespread tampering with test papers and concluded that Hall stood at the center of “a culture of corruption.”

Special investigator Michael Bowers, a former state attorney general, told USA Today in 2013 that interrogating teachers in the scheme had left him in tears.

“The thing I remember most was talking to some of the teachers who had been mistreated, mostly single moms,” he said. “And it’s heartbreaking. They told of how they had been forced to cheat.” One told him, “I had no choice.”

‘On the backs of babies’

Hall retired in 2011, but on March 29, 2013, a Fulton County grand jury indicted her and more than 30 others in what Willis called a conspiracy comprising administrators, principals, teachers and even a school secretary.

Similar to this week’s indictments, the Atlanta defendants faced charges of racketeering, conspiracy and making false statements. Hall also faced theft charges because her rising salary was tied to test scores — in 2009, the year she was named Superintendent of the Year, she got a $78,000 bonus, prosecutors noted.

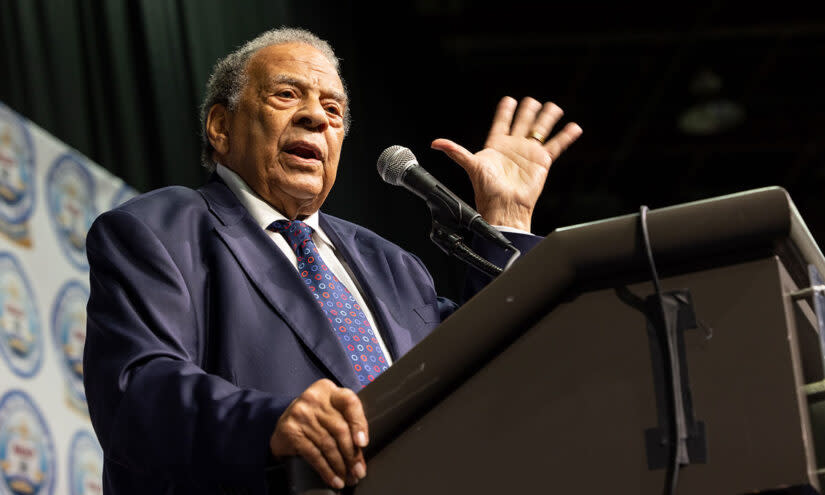

If convicted, Hall could have served as many as 45 years in prison, but she soon fell ill and the judge in the case indefinitely postponed her trial. At an April 2014 hearing, Andrew Young, a former Atlanta mayor and United Nations ambassador, rose in the courtroom and asked the judge to be “merciful” and drop the case against her.

“Let God judge her,” he said.

Hall died of breast cancer in 2015, at age 68.

Public opinion on the case was sharply divided, with many Black commentators accusing Willis of overreach. But eventually, 34 of Hall’s subordinates faced criminal charges.

Brittney Cooper, a professor of Women’s and Gender Studies and Africana Studies at Rutgers University, wrote: “Scapegoating Black teachers for failing in a system that is designed for Black children, in particular, not to succeed is the real corruption here.”

Cooper noted that former Washington, D.C., Schools Chancellor Michelle Rhee, who is Korean-American, had also been under scrutiny for creating a “culture of fear about test scores.” An investigation by USA Today revealed findings similar to Atlanta’s, but an inspector general report found no evidence of widespread cheating and Rhee never faced prosecution.

While most of the Atlanta educators eventually pleaded guilty to avoid jail time, 12 went to trial in 2014. As with the Trump case, this one was complex: Jury selection took more than six weeks, and jurors sat through complex statistical analyses of answer-sheet erasure patterns, among other matters. At a few points in the trial, a dozen or more lawyers offered different versions of events.

In an early case that went to trial in 2013, Willis said supervisor Tamara Cotman worked to protect educators’ jobs by advising principals under investigation not to cooperate with state investigators — a charge Cotman denied — and by vowing to return high test scores at any cost.

“She did it on the backs of babies,” Willis told jurors during closing arguments. The jury acquitted Cotman, who was later convicted of other charges in the larger case.

In court, Willis told the jury of “cheating parties” at which educators got together to erase children’s incorrect answers on test sheets and pencil in correct ones. At a few of the parties, she said, educators “ate fish and grits — I can’t make this up.”

The jury convicted 11 of the 12 of racketeering and other charges.

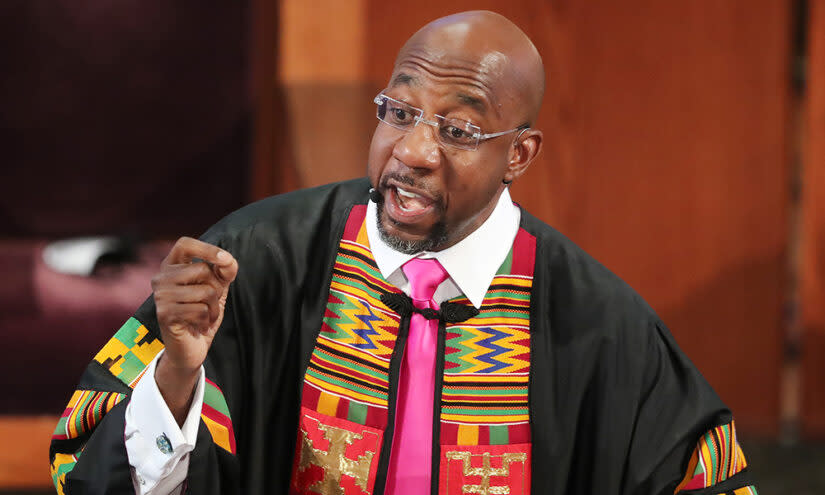

The Rev. Dr. Raphael G. Warnock, at the time senior pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church — he now serves as a U.S. Senator — told The New York Times, “There’s no question that this has not been our finest hour. It’s a dark chapter, but it’s just that. It’s a chapter.”

In 2015, commentators Van Jones and Mark Holden wrote that the educators convicted in the case were “the latest victims of overcriminalization,” facing serious jail time because of Willis’s “unprecedented use” of RICO. Three were sentenced to seven years in prison, they noted, while others received one- or two-year sentences if they didn’t accept plea deals.

“These punishments do not fit the crimes,” they wrote.

Since then, several of the defendants have loudly proclaimed their innocence, even as they’ve served prison time or pursued appeals to avoid it. A handful of those cases remain outstanding. In several instances, they and their defenders say they’ve spent their life savings pursuing appeals.

In 2019, Shani Robinson, one of those found guilty, co-authored a book about the ordeal. In an interview, she told NPR, “the thought of being blamed for something that I did not do is horrifying. … I felt like if I was on the right side of justice, that one day I would be vindicated. That was the moment that I decided that I would never take a plea deal.”

But many parents saw it differently.

Shawnna Hayes-Jocelyn had three of her four children in classes at schools affected by the cheating. She said Willis rightly brought RICO charges.

“You’d better believe she did the right thing, because that was the worst Black-on-Black crime example that could have ever happened around education,” she told The 74. “Because what they did to those children is that they didn’t give those children options and opportunities.”

Hayes-Jocelyn said her mind was made up once she read the state report that alleged widespread cheating among educators.

“When I read that report and saw what was happening in that school system, yeah, people said, ‘Oh, this is RICO. We think about RICO as organized crime.’ I said, ‘This was organized crime.’”

Those familiar with Willis’s work say she’s tenacious. Atlanta NAACP president Gerald Griggs, one of the defense attorneys in the cheating trial, told The Guardian this week that Trump is “going to be very surprised when he’s sitting across from her for months on trial. He’ll find out how great of a lawyer she really is.”

Asked in 2021 if she had regrets about pursuing the school cheating cases, Willis was blunt, telling the Times that by going after teachers, principals and administrators, she was “defending poor Black children.” Public education, she said, offers these children their only chance to get ahead. “So if what I am being criticized for is doing something to protect people that did not have a voice for themselves, I sit in that criticism, and y’all can put it in my obituary.”