Trump’s Old Legal Arguments Are Coming Back to Haunt Him

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This is part of Opening Arguments, Slate’s coverage of the start of the latest Supreme Court term. We’re working to change the way the media covers the Supreme Court. Support our work when you join Slate Plus.

Back when Donald Trump was president, critics delighted in finding old Trump tweets that contradicted his new positions. We have now reached the next evolution of this phenomenon: Legal arguments Trump once made in court are coming back to haunt him. And the newest iteration of self-conflicting Trump arguments will be the most significant yet.

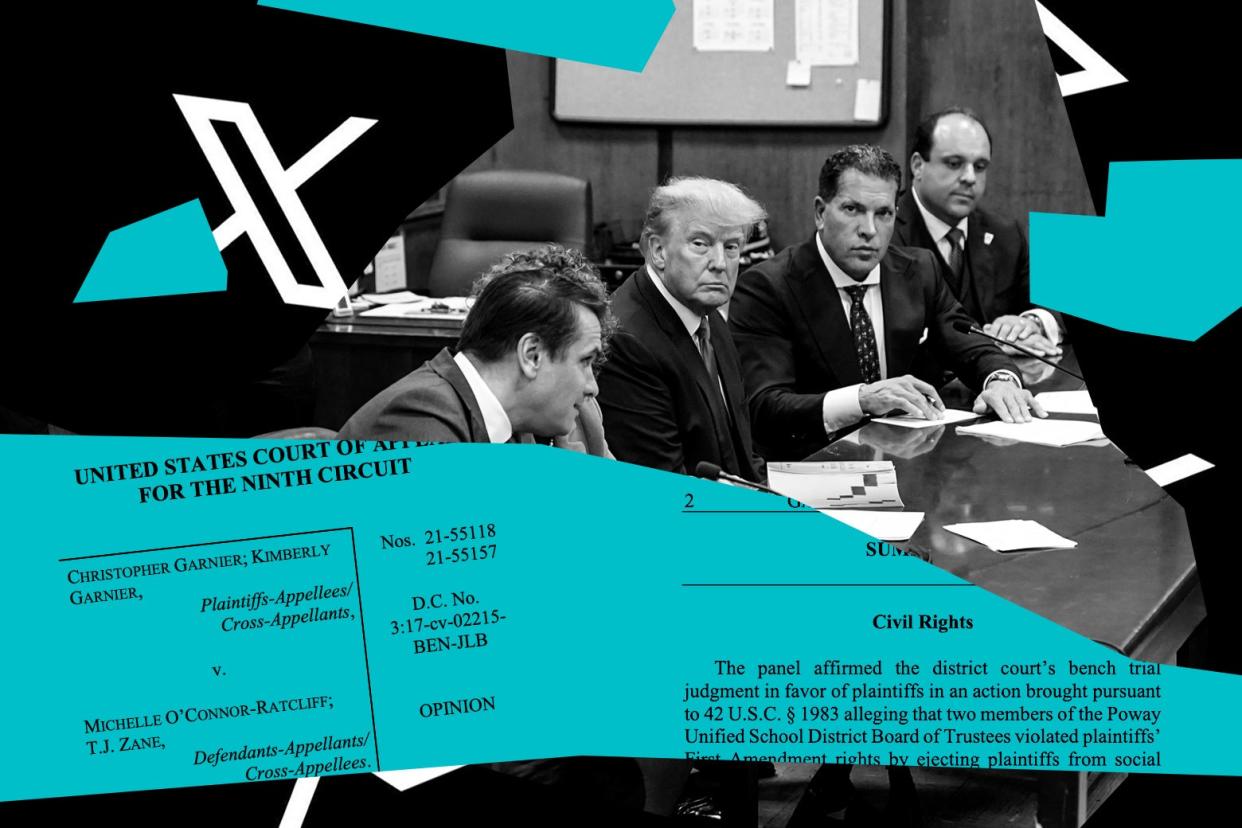

The tension will be front and center on Tuesday, when the Supreme Court hears oral argument in a pair of major cases. Both cases, O’Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier and Lindke v. Freed, involve First Amendment lawsuits against government officials who blocked their followers on social media. Importantly, the officials have asked the court to adopt a legal position that President Trump advocated in 2020 when he, too, was sued for blocking critics on Twitter: that their social media activity was private, nonofficial action to which the First Amendment does not apply.

If the court’s conservatives agree with this view, they will preserve the control officials have over their social media accounts. Yet such a ruling would have another profound consequence: It would jeopardize Trump’s recently filed motion to dismiss his federal criminal indictment for election interference on the basis of so-called official immunity.

To see how, start with a basic rule concerning how the law applies to individual government officials. When they are doing their jobs, such individuals act under a trade-off. On one hand, because their actions are those of the government, they are bound to follow rules that limit government power, such as the Constitution’s prohibition against abridging free speech. On the other hand, the law also affords these officials a degree of immunity to protect them from the threat of litigation.

Significantly, both the Constitution’s limits and the immunity defense apply only when a government employee is acting as an official—not when they act as a private citizen. As the Supreme Court wrote in Nixon v. Fitzgerald, the case that recognized presidential immunity from civil damages liability (but that did not address criminal prosecution), any immunity extends only to “acts within the ‘outer perimeter’ of [the president’s] official responsibility.”

The big question, then, is how to know whether a president is acting pursuant to his official responsibilities or instead acting as a private citizen.

In Trump’s new brief claiming official immunity from prosecution, his legal team has advanced an extremely broad view of the president’s official responsibilities: They include actions he takes even if on “matters for which the President himself bears no direct constitutional or statutory responsibility.”

It’s easy to see why such a sweeping definition of presidential job responsibilities is vital to Trump’s defense: The actions he is alleged to have taken to overturn the 2020 election do not fall within any normal sense of a president’s constitutional or statutory job description. No constitutional or statutory provision obligates a president to recruit false slates of electors, obstruct the congressional certification of an election result, or deprive Americans of their right to vote.

The problem for defendant Trump is that his capacious view of the president’s official duties is the opposite of the position he and his lawyers advanced in the Supreme Court when, as president, he was sued for blocking his Twitter followers. Then, in 2020, Trump filed a brief in the Supreme Court arguing that he could be considered to be acting as a government official only if his action was “pursuant to [a] power which he is authorized to exercise by law”—which is to say, a power authorized by the Constitution or a statute.

Trump’s briefs contain still more internal contradictions. Facing the threat of jail time today, Trump now argues that “making public statements on matters of public concern, including Tweets … is an official action” that triggers official immunity. Yet in his 2020 brief, Trump argued to the court that when he used Twitter “to communicate with the public about official actions and policies of his administration,” he was acting as a private citizen, not a government official.

The hypocrisy is apparent. When Trump was president, he wanted to evade liability for constitutional violations. So he argued that he was acting as a private citizen unconstrained by the Constitution. But now that he is a criminal defendant, he has reversed course because private citizens are not entitled to official immunity: Even his most private-seeming acts, he now claims, are “official” and thus immune from prosecution.

To be sure, the social media cases now before the Supreme Court no longer involve Trump himself; the court dismissed the case against him as moot once he lost the 2020 election. But the political through line is evident: The partner at Jones Day who represents the public officials in one of the current social media cases is the same lawyer who represented Trump in his 2020 brief before the court on the same Twitter-blocking issue.

The upshot is that the pending cases before the Supreme Court are about much more than the First Amendment’s applicability in an age of social media. They are cases that could also spell trouble for Trump’s defense team. For if the court agrees with the argument he once propounded—that the president’s official responsibilities should be construed narrowly—it will be difficult to see why the same rule shouldn’t apply to Trump’s claim to official immunity.

Moreover, even if the court rejects a narrow definition of official action in the social media cases, that will do little to guarantee Trump’s success in his pending criminal case. There remain many other ways the court could reject his immunity defense, including the distinct possibility that such immunity is inapplicable in criminal proceedings.

The Constitution itself seems to suggest this conclusion insofar as it allows for an impeached president to be “subject to indictment, trial, judgment and punishment.” It would have been strange for the founders to enumerate those possibilities if presidents all along enjoyed absolute immunity from criminal prosecution.

The law, in short, is closing in on the former president. And in the case of his effort to claim immunity from prosecution, he has largely himself—and his prior inconsistent legal positions—to blame.