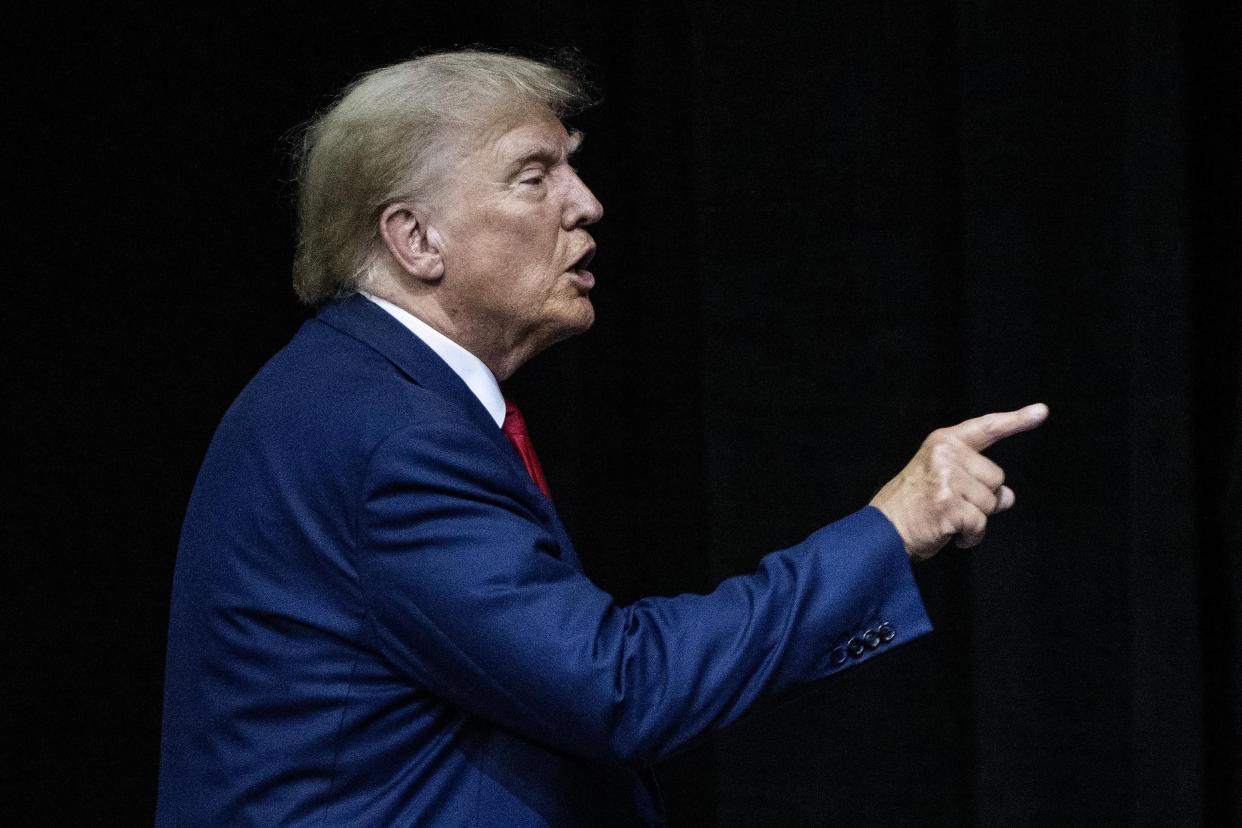

Trump’s Ploy to Evade Punishment for Jan. 6 Is Coming Into Focus

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Donald Trump’s lawyers finally filed their long-promised request for recusal on Monday afternoon, asking U.S. District Judge Tanya Chutkan to disqualify herself from the former president’s Jan. 6 case. Trump faces criminal charges in the District of Columbia for his alleged role in the insurrection, and Chutkan, a Barack Obama appointee, was randomly assigned to oversee the case. Early on, Trump dismissed the judge as “biased and unfair” on Truth Social; now, six weeks later, his legal team has translated that garbled post into a formal motion.

Or at least, they’ve attempted to. This play is so poorly conceived and executed that it is difficult to believe the former president’s lawyers actually want to succeed. Monday’s motion is so tardy that Chutkan could simply deny it as untimely. It fares no better on the merits, fox-trotting around an insurmountable Supreme Court precedent strictly limiting recusal that dooms the whole endeavor. It seems, then, that Trump’s real move here is extralegal: He wants to undermine Chutkan’s authority to preemptively delegitimize any sentence she hands down. The audience for this recusal motion isn’t Chutkan. It’s the court of public opinion—the voters, activists, media figures, GOP lawmakers, aspiring insurrectionists, and future fake electors who might all help Trump refuse to accept a guilty verdict and the sentence that accompanies it.

Federal law requires a judge to recuse “in any proceeding in which his impartiality might reasonably be questioned.” Trump and his lawyers allege that Chutkan met this standard when she alluded to the former president in other Jan. 6 cases. Here is how she did that: At one sentencing hearing, the judge reminded an insurrectionist that “the people who mobbed that Capitol were there in fealty, in loyalty, to one man. … It’s a blind loyalty to one person who, by the way, remains free to this day.” At a different sentencing hearing, Chutkan responded to the defendant’s complaint that low-level rioters faced charges while the leaders of the coup seemingly walked free. She said:

You have made a very good point, one that has been made before—that the people who exhorted you and encouraged you and rallied you to go and take action and to fight have not been charged. That is not this court’s position. I don’t charge anybody. I don’t negotiate plea offers. I don’t make charging decisions. I sentence people who have pleaded guilty or have been convicted. The issue of who has or has not been charged is not before me. I don’t have any influence on that. I have my opinions, but they are not relevant.

According to Trump, these remarks, taken together, reveal Chutkan’s belief that he “should be charged” and “imprisoned,” and that she “placed blame on President Trump” without “due process.”

In reality, these comments merely reflect a frustration, widely shared among Chutkan’s colleagues, that the thousand-plus Jan. 6 prosecutions have mostly targeted rioters with no direct connection to the leaders of the criminal conspiracy. It is perfectly reasonable, and not a sign of bias, for a judge to express frustration with the churn of convictions for low-level offenders and the absence of charges for those at the top. It does not violate due process for a judge to recognize that, in case after case, rioters have explained that they were following orders from Trump and his allies—or to note that the men who gave these orders have largely escaped culpability. (Chutkan made these comments before this summer’s prosecutions of the former president; they remain just as appropriate today as they were then.)

But set all that aside. There are two fatal problems with the recusal motion. First, it’s far too late for the court to consider it. Under D.C. Circuit precedent, which binds Chutkan, a party “must bring a disqualification motion at the earliest possible moment after obtaining knowledge of facts demonstrating the basis for such a claim.” This rule prevents parties from deploying these motions as a delay tactic. Yet that is what Trump now seeks to do. As his own Truth Social post illustrates, he and his legal team have known about Chutkan’s alleged bias since early August. His lawyers should have filed the motion to disqualify within days of the case’s assignment. Certainly, they could have: It runs a mere nine pages and identifies comments that they knew about from the start. Nevertheless, Trump’s lawyers waited until after the imposition of a protective order and a trial date before abruptly asking Chutkan to take a hike. The judge would be well within her rights to deny the motion as untimely and move on.

It appears, however, that Chutkan has chosen instead to consider the motion on the merits—she has already asked the government for a response. That response should be straightforward, because Supreme Court precedent totally forecloses Trump’s argument. In 1994’s Liteky v. United States, a majority of the court, led by Justice Antonin Scalia, created a categorical rule for recusals under the relevant statute: A judge’s statements made during a legal proceeding, based on facts and opinions derived from a legal proceeding, cannot serve as grounds for recusal. As Scalia put it:

Opinions formed by the judge on the basis of facts introduced or events occurring in the course of the current proceedings, or of prior proceedings, do not constitute a basis for a bias or partiality motion unless they display a deep-seated favoritism or antagonism that would make fair judgment impossible. Thus, judicial remarks during the course of a trial that are critical or disapproving of, or even hostile to, counsel, the parties, or their cases, ordinarily do not support a bias or partiality challenge.

The lone exception is when a judge’s comments are so egregious, so wildly prejudiced, that they “display a deep-seated favoritism or antagonism that would make fair judgment impossible.” That bar is impossible to meet in all but the most shocking circumstances. For instance, in August, an appeals court ordered the recusal of a judge who expressed disgust that a defendant would exercise his fair trial rights and declared from the bench: “This guy looks like a criminal to me. This is what criminals do. This isn’t what innocent people who want a fair trial do.” Chutkan’s comments are (obviously) incomparable to this outburst; they are the reflections of a judge with a front-row view of the uneven culpability for Jan. 6, not malicious insults toward the defendant.

Trump’s lawyers barely acknowledged Liteky in their recusal motion. In a half-baked aside, they feebly argued that “the public can reasonably understand” Chutkan’s opinions to “derive from extrajudicial sources” rather than courtroom proceedings. If that were true, the allegation might get around Liteky’s categorical bar, but it is demonstrably untrue. The hearing transcripts reveal that Chutkan scrupulously adhered to the record, drawing her opinions solely from the facts of the cases before her. There is not a shred of evidence that her views derive from any information gleaned outside the courtroom. Nor is there any reason for the public to believe her conclusions came from some secret, outside source rather than the multiple Jan. 6 cases on her docket. Under Liteky, then, the recusal motion is dead on arrival.

So what should we make of Trump’s play? It is notable that his lawyers were initially reluctant to demand disqualification, and he seems to have cajoled them into doing it; that detail helps explain why the motion feels more like a political strategy than a legal one. It’s a familiar political strategy: Trump has a lengthy and sordid history of attacking judges who rule against him or seem poised to do so, denying their impartiality and rejecting their very authority. He condemned Robert Mueller (a registered Republican) as a partisan fanatic all throughout the special counsel’s investigation and has repeated the tactic with Jack Smith. And he promoted widespread claims of voter fraud before and after the 2020 election, decrying his loss as illegitimate.

With a trial set for March 2024, Trump’s Jan. 6 case is careening toward a very possible guilty verdict and prison sentence. If the former president is held liable for Jan. 6 and gets sentenced by Chutkan, he will surely exploit her alleged bias as an excuse to fight his punishment the only way he knows how: rallying his supporters to reject the court’s power and try to change the outcome by any means necessary. He ran this playbook on Jan. 6. He could absolutely run it against a federal court.

It is incumbent on the public, the legal community, and the media to hammer home the complete lack of merit behind his push for recusal. Chutkan has every right to oversee this case. She is as qualified and unbiased as federal law requires. Those who question that reality are only helping Trump evade responsibility for his previous crimes—and potentially helping him lay the groundwork for new ones.