Trump Says He’s Going to Testify in His New York Civil Trial. Fat Chance.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

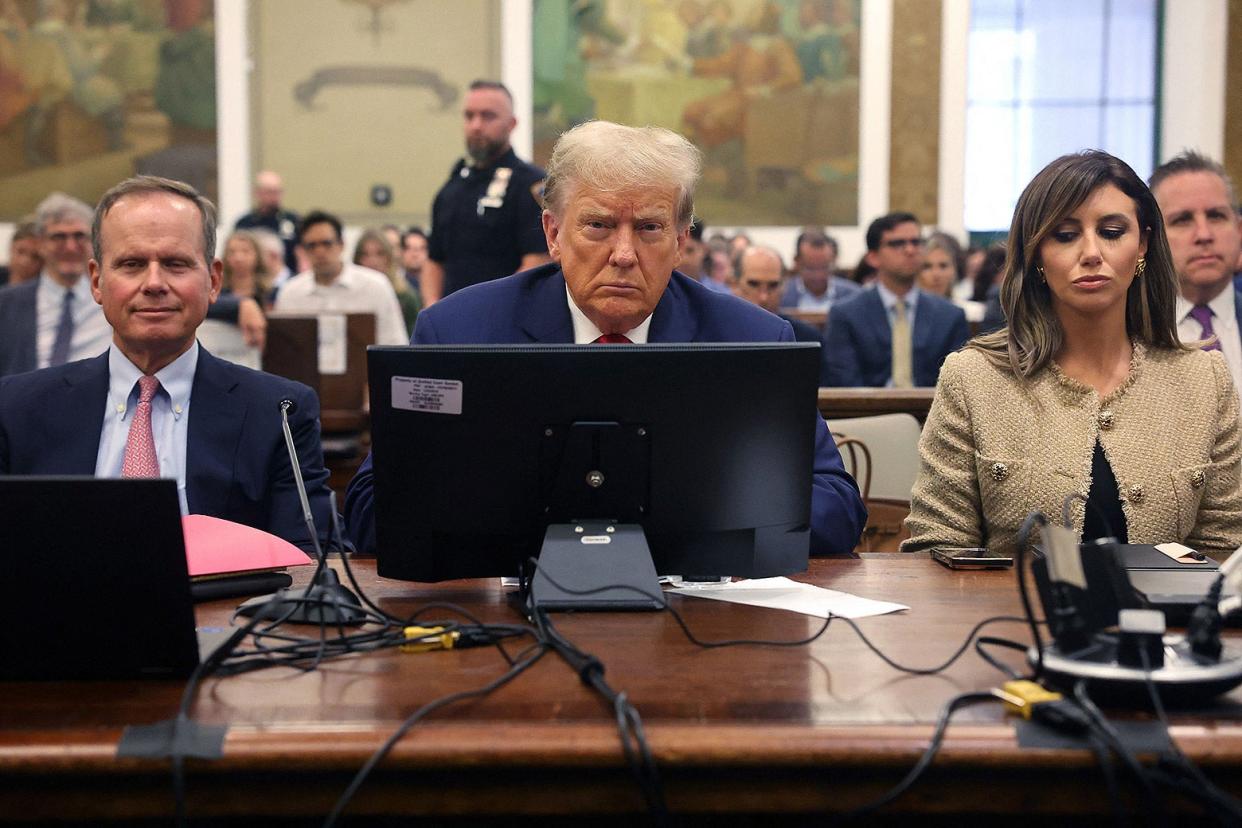

Having invested just two and a half days of personal time in his New York state civil fraud trial, Donald Trump has headed back to Mar-a-Lago. Whether he returns to Judge Arthur Engoron’s courtroom for any portion of what is expected to be a lengthy trial remains to be seen.

That decision, like all Trump strategies, will focus first on political considerations and will encompass legal reality only when there is no other choice.

A prime example of the tension between Trump political theater and sensible legal strategy is Trump’s and his attorneys’ claims that he will testify in the civil fraud trial. Despite such multiple announcements—intended to assure Trump’s base that he has nothing to hide and is fighting the charges head-on—his voluntary return to court as a witness in his own defense is most unlikely, as it is clearly the worst of the bad legal choices he faces.

As I observed in Slate last year concerning the dangers in Trump’s potential testimony in a possible federal criminal trial: “The list of questions Donald Trump would be unable to answer is so long that the hardest task for whomever would cross-examine him would be to whittle it down to the best three days’ worth of material.”

That reality is even more problematic for the former president in the New York civil case, as New York state law provides the attorney general’s office especially wide leeway to cross-examine Trump. Per Rule 6.11’s impeachment provisions, a witness can be confronted with any evidence “that has a tendency in reason to discredit the truthfulness or accuracy of the witness’s testimony.” As a result, every lie told will be on the table, subject only to the limitations imposed by a judge he has personally attacked, and whose law clerk he has smeared.

Thus, the only beneficiaries of Trump’s testimony will be the state of New York and, of course, waiting in the wings, the Department of Justice, a consequence far more significant than stoking up the base for a few extra donor dollars.

But can’t the state call Trump in their own case as a “hostile” witness, thus allowing them to ask leading questions and impeach his credibility? Of course, but in that capacity, Trump can invoke his privilege against self-incrimination and not answer. Despite having a long history of denigrating the invocation of privilege—“If you are innocent, why are you taking the Fifth Amendment?”—this will not be the first time he has done so, nor the last time he will.

While, because it is a civil case, Judge Engoron can draw reasonable negative inferences from his invocations of privilege, the potential harm will surely be less than the debacle of any attempts to explain the inexplicable and being confronted with a lifetime of lies, some of which are the bases for his current, multiple criminal exposures.

Donald Trump is surely aware that he will not escape a financially devastating result in the New York civil fraud case, and so, consistent with his strategic response to all his legal woes, the former president is using the civil fraud trial as a fundraising and campaign event. As is widely recognized, without a legal defense Trump must rely on a political one that he hopes will return him to the insularity and the power of the White House.

Combined with his attempts to delay each of the proceedings to escape final judgement at least until the July 15, 2024, Republican convention—when his appeals to the MAGA base are expected to have given him a huge lead in delegates—the Trump strategy threatens to create an unprecedented political and constitutional crisis.

Thus, regardless of how devastating a financial blow will be struck by Judge Engoron by, say the end of 2023 or early 2024, the appeals process will likely continue past the early March 2024 onset of Republican primaries. While Trump is most unlikely to obtain a reversal, or even a meaningful reduction, of the grave financial penalties Judge Engoron will likely impose, he will still get what he needs most—time to garner convention delegates.

In the interim, as the evidence of civil fraud mounts in the Manhattan courtroom, far from a courthouse he will avoid for as long as possible, the disgraceful insults hurled against the American legal system and its participants and the baseless claims of victimhood will continue.