Trump wants it both ways on ‘declassified’ documents

Former President Trump’s legal team is trying to have it both ways — insinuating he declassified the documents stored at his Florida home without directly claiming he did so.

Trump’s legal team in a Monday court filing failed to fully premise its argument on the excuse the president has repeatedly offered since confirming his home was search: that he had already declassified documents at his Mar-a-Lago estate.

Instead, it noted he had the power to do so without “approval of bureaucratic components of the executive branch” — seemingly offering an air of mystery around whether the former president ever declassified the tranche of more than 300 intelligence documents in his home.

But experts say if you take Trump at his word, the secretive nature through which he would have declassified those records is itself problematic.

“If he did, and he did it in the way that he claims he did, that’s actually not really the flex he thinks it is. It actually suggests that he had a nefarious purpose,” Asha Rangappa, a lecturer at Yale University and a former FBI special agent, said of Trump.

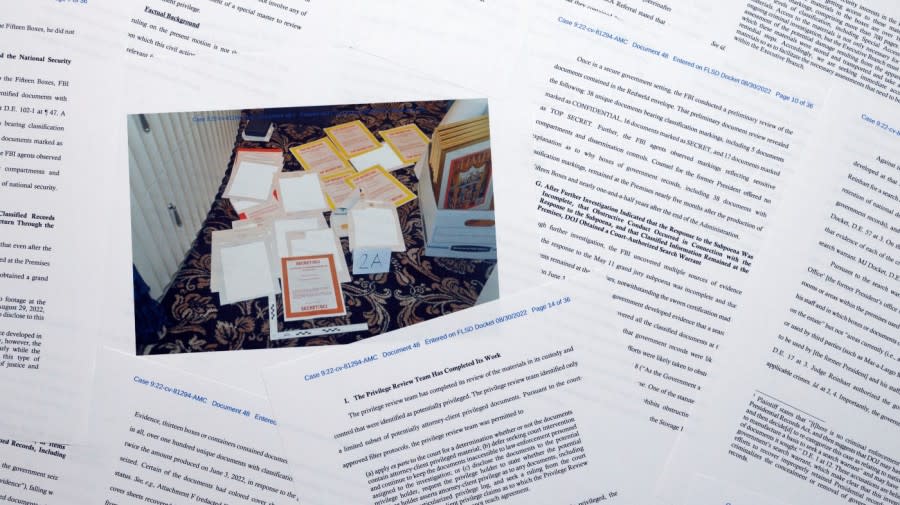

Pages from a Department of Justice court filing in response to a request from the legal team of former President Donald Trump for a special master to review the documents seized during the Aug. 8 search of Mar-a-Lago. Included in the filing was a FBI photo of documents that were seized during the search. (AP Photo/Jon Elswick)

Sitting presidents have broad power to declassify documents, but doing so sets off a chain of events, including notification of the many intelligence agencies that produce and manage that information.

Rangappa said a failure to alert the intelligence community shows Trump wanted the information he took to still have value — something that would be lost in the declassification process.

“The full declassification process will then end up protecting sources and methods, so that if these secrets become known to people, they can’t do anything with it,” Rangappa said, essentially “neutralizing” the information.

Rangappa gave the example of a list of all U.S. informants scattered across the globe. If those people became compromised, the U.S. would need to spring into action.

“They would be moved, they would be protected [and] they would be exfiltrated so that when that list becomes public or when our adversaries get a hold of that list, they can’t do anything to those sources because they’ve already been protected. … In other words, to go through the whole declassification process renders this information largely invaluable to people who might be interested in it because they can’t really take advantage of it,” she said.

The same thing would happen in the case of other methods for collecting and intercepting information.

Kash Patel, who most recently served as chief of staff to Trump’s secretary of Defense, told The Wall Street Journal he witnessed Trump give verbal declassification orders, but they appear to have been related only to the investigation into Trump’s ties to Russia, and it’s not clear how that order would have been carried out.

“If your defense is ‘I declassified it, but I did it really secretly so that none of these things could be neutralized,’ then the only reason you would do that is if you still wanted these sources and methods to continue operating, even as you treated these secrets as being something that you could disseminate or share,” Rangappa said.

Trump’s motives for retaining the roughly 300 classified records or nearly 10,000 government documents in his home are not clear. In court filings, the Department of Justice (DOJ) has noted that Trump’s legal team has never offered an explanation for why he retained the records beyond arguing that he has a right to do so under executive privilege.

The DOJ noted in a filing last month that Trump and his team never raised the declassification claim in their months of negotiations, and as a defense, it may do little considering the government argues he has no right to retain any of the records.

Pages from a FBI property list of items seized from former President Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago estate and made public by the Department of Justice. FBI agents who searched the home found empty folders marked with classified banners. The inventory reveals in general terms the contents of the 33 boxes taken during the Aug. 8 search. (AP Photo/Jon Elswick)

But experts say the revelation that Trump’s declassification claim may have come only after the fact indicates there would have been little benefit in doing so.

“There’s no value in having information that everybody else has,” said Kel McClanahan, executive director of National Security Counselors, a nonprofit law firm specializing in national security law.

“He wanted this information because it was valuable to him, and it was extra valuable because he knew he was one of the only people that had it,” McClanahan added.

Declassification is not a defense for the charges laid out in the DOJ warrant to search Trump’s home. The Espionage Act deals only with “national defense information,” while another one of the statutes covers willful concealment of government records.

Rangappa lamented that Trump appears to be using declassification claims as a Get Out of Jail Free card but noted that the status is not stagnant — some presidents have opted to reclassify information declassified by their predecessors, another detail she said makes Trump’s storage of the documents alarming.

The Trump legal team’s failure to directly assert the claim is also telling given the span of time the records were sought — a process that started with outreach from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) just months after Trump left office.

“They had over a year of interactions with NARA. They’ve had months of interactions with the Department of Justice. They’ve had two legal filings and now one court hearing. And not once in any of those interactions have they claimed that any information at issue was declassified,” said Brian Greer, a former CIA attorney.

“They have claimed so on television, but there’s no criminal penalty for lying on television. There are, however, criminal penalties for lying to federal agencies, to federal investigators and to courts,” he added.

Even on Friday, Trump’s team seemed to raise the specter that he may have declassified the documents, writing only that the government “wrongly assumed that if a document has a classification marking, it remains classified in perpetuity.”

The Justice Department on Thursday asked a federal district court judge to reconsider her decision granting Trump’s request to allow a special master to review the documents, asking that it be allowed to carry on with its review of all the classified records.

A page from the order granting a request by former President Donald Trump’s legal team to appoint a special master to review documents seized by the FBI during a search of his Mar-a-Lago estate. The decision by U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon came despite the objections of the Justice Department, which said an outside legal expert was not necessary in part because officials had already completed their review of potentially privileged documents. (AP Photo/Jon Elswick)

It remains unclear how nearly 11,000 government documents, classified and unclassified, made it to Mar-a-Lago and the extent Trump played a role in directing documents to be removed and stored there. Some of the classified records, however, were found in his office among his personal belongings. Also among the tranche are empty folders that once housed the documents.

Throughout his presidency, intelligence community officials were often alarmed by Trump’s cavalier attitude toward classified information; Trump once tweeted a photo of sensitive surveillance image of an Iranian space facility.

Recent reporting from The New York Times indicates he would occasionally ask to hold on to various documents.

Former intelligence officials told the outlet Trump gravitated toward charts and other visuals and was particularly interested in information about how he was perceived after meeting with other world leaders as well as intelligence gathered about the personal lives of statesmen, including their extramarital affairs.

McClanahan said classification status alone may not have generated interest in the documents.

“He saw the value in the information, not in the fact that it was classified,” McClanahan said.

“The nature of the intelligence community is to classify things that are damaging, to classify information that could hurt national security. By definition, if they’re doing it right, anything they classify would damage the national security, which would make it important. So I think it’s sort of a mirage, it’s an optical illusion, that he took information because it was classified. He took the information because it was useful information. It was classified because it was useful information,” he added.

It’s not clear what was among the classified records recovered from Mar-a-Lago, but court filings indicate that they include some of the most restricted information, including Special Access Programs materials limited only to those with a specific need to know.

Also collected in the search were documents dealing with information about the “President of France” and Trump’s pardon of ally Roger Stone.

“I think that you’d probably be able to file most of this information into one of three categories: It’s information that can hurt him, so he doesn’t want other people to have it; information that can hurt other people, and he wants to have it; or information that other people would want, and they’ll have to come to him to get it,” McClanahan said.

“Between those three categories I think you can probably account for like 95 percent of all the materials he took, whether they be classified or unclassified,” he said.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to The Hill.