Trump weighs conditioning foreign aid on religious freedom

Aides to President Donald Trump are drafting plans to condition U.S. aid to other countries on how well they treat their religious minorities, two White House officials said.

The proposal is expected to cover U.S. humanitarian and development assistance and could be broadened to include American military aid to other countries. If the proposal becomes reality, it could have a major effect on U.S. assistance in a range of countries, from Iraq to Vietnam. Its mere consideration shows how much the White House prioritizes religious freedom, an emphasis critics say is really about galvanizing Trump’s evangelical Christian base.

But experts on U.S. aid also warn that picking and choosing which countries to punish could be a difficult task, not least because several countries that are partners or allies of the United States have terrible religious freedom records.

The effort comes as Trump faces an impeachment inquiry that hinges in part on whether he froze military aid to Ukraine as a way to pressure its government to investigate his political rivals.

Two White House officials confirmed the basics of the religious freedom aid-conditioning plan. They stressed that the idea is in its early stages and an executive order is still being drafted, meaning questions about whether military aid will be covered remain unanswered.

One said imposing sanctions is being weighed as a method of punishment, too. The other said the idea is patterned in part on existing U.S. legal requirements that restrict aid to countries that do poorly on an annual U.S. report on human trafficking.

During his U.N. General Assembly speech in September, Trump signaled that his administration would keep making religious freedom a priority.

“Hard to believe, but 80 percent of the world’s population lives in countries where religious liberty is in significant danger or even completely outlawed,” Trump said. “Americans will never tire in our effort to defend and promote freedom of worship and religion.”

As they try to push that vision forward, administration aides are considering using the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom’s lists of offending countries as their guide for deciding which countries should have their aid withheld or face sanctions, the White House officials said.

The commission's regular reports rank countries in tiers. Its lists can differ from countries of concern separately designated by the secretary of State, and they often are longer. Among its Tier 1 countries — considered the worst offenders — are U.S. partners such as Saudi Arabia and adversaries such as Iran.

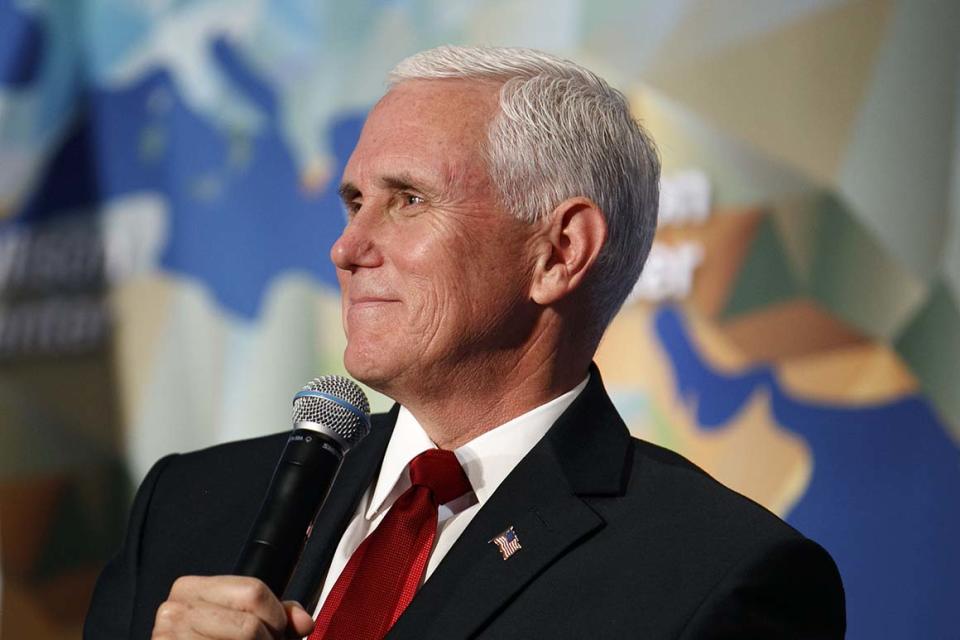

Representatives from the National Security Council, the Domestic Policy Council, the State Department and Vice President Mike Pence’s office have been meeting to discuss the executive order, which Trump has not yet seen, the White House officials said.

Pence’s role could prove a flashpoint.

He’s a deeply conservative Christian and a key liaison to evangelical Trump backers. And while his message is generally couched in terms of the need for all people to have religious freedom — he has criticized China’s mistreatment of Uighur Muslims, for instance — critics say he emphasizes Christians. Pence also is facing scrutiny for his role in directing U.S. aid to favored Christian groups abroad.

Asked for comment, his press secretary, Katie Waldman, said, “The vice president is always proud to support religious freedom both here at home and abroad.”

One evangelical leader close to Trump hailed the idea as something that’s been needed “for a long time.” "Obviously the devil is in the details about how it is arrived at and carried out as a matter of policy," this person added, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Others observers were more wary.

“Oh, man, there’s so many ways that could go wrong,” said Jeremy Konyndyk, a former senior aid official in the Obama administration.

He said that, depending on how strictly the administration interprets the idea of “religious freedom,” it is likely to hit national security concerns about protecting certain allies. Egypt and India, for example, arguably have religious freedom issues, he noted, but both receive U.S. aid.

Egypt, where the Christian minority has long complained of discrimination from majority Muslims, receives roughly $1.4 billion in U.S. assistance a year, most of it for security purposes. India, where tensions between Muslims and Hindus are on the rise, has received tens of millions in U.S. aid in recent years, government data shows.

The religious freedom commission categorizes both as Tier 2 countries.

There’s also “not a lot of evidence or experience to suggest that this kind of conditioning of aid is actually terribly effective in achieving its goal,” Konyndyk added, saying that even the human trafficking law has had limited success in curbing such activities, despite how much countries hate the bad publicity.

Also, governments are not the only entities that persecute religious minorities, Konyndyk said. Often, religious persecution is a social or cultural problem over which a government has limited control.

“A community is not going to stop persecuting another community because some other part of the country is going to get the aid cut,” he said.

One strong likelihood is that any executive order will include a clause that gives the president or a designee the ability to exclude a country from aid restrictions on grounds that it is in the U.S. national security interest.

Trump’s approach to foreign aid has long drawn criticism, and not because of what might have led to the hold on the military funds for Ukraine. Critics say Trump has “weaponized” foreign aid to pursue specific political objectives, and that it has had little success.

He’s effectively ended U.S. aid to Palestinians in a failed effort to push them to negotiate peace with Israel. He also used the lure of foreign aid to try to get Venezuelans to rise up against their dictator, Nicolás Maduro — another unsuccessful effort.

On a macro level, the Trump administration is generally hostile to foreign aid, having proposed multiple times to slash it significantly. Congress has prevented such cuts.

The linking of aid to religious freedom would not be a surprising move by Trump given his administration’s intense focus on the issue.

During the U.N. General Assembly in September, Trump announced a $25 million commitment to support religious freedom.

Weeks earlier, his administration launched the International Religious Freedom Alliance, a vehicle that brings together countries to promote the cause. The administration also has held two major gatherings of foreign ministers focused on promoting religious freedom.