Trump’s ‘West Point Mafia’ Faces a Loyalty Test

On May 28, 1986, newly commissioned 2nd Lt. Michael Pompeo stood at attention in Michie Stadium at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, first in his class. The career he was about to launch would take him from commanding a tank platoon in Germany to a seat in Congress, and ultimately to the right hand of President Donald Trump as secretary of State.

Also on the field that day was classmate Mark Esper, who this July landed right next to Pompeo in Trump’s Cabinet, confirmed as secretary of Defense. Their West Point classmates Ulrich Brechbuhl and Brian Bulatao also hold senior State Department posts as Pompeo’s top lieutenants, while at the other end of the National Mall, inside the Capitol, classmate Rep. Mark Green of Tennessee has emerged as one of Trump’s leading defenders on the House Committee on Oversight and Reform.

Thanks in part to Trump’s fixation on appointing current and former military officers to key posts, and in part to his tendency to take advice from a small circle of advisers, the West Point class of 1986 has grown into a profoundly influential cohort in American foreign and military policy. In the annals of the military service academies, its rise to the top puts it on a par with the class of 1915, which bred the commanders of World War II and a U.S. president.

The link that brought them into Trumpworld is David Urban, the lobbyist, CNN commentator and Trump confidant—and another member of the West Point class of ‘86—whose support of his fellow cadets helped Pompeo and Esper land their Cabinet posts.

Today, the tight-knit group of graduates—some cheekily refer to themselves as the “West Point Mafia”—constitutes a uniquely powerful circle at the highest levels of government. They consult each other on matters of state and also lean on each other in matters more intimate, in informal dinners and social gatherings around Washington with their spouses. And they have banded together to raise $23 million for a scholarship fund for the children of fallen soldiers, in honor of one of their classmates who was killed on active duty in Afghanistan a decade ago.

Now, the loyalty of all the president’s top advisers is being severely tested as the impeachment inquiry bears down on White House staff and the top rungs of the State Department and the Pentagon. For the West Point Mafia, that loyalty could start to conflict with their alma mater’s honor code, which— as some of their fellow West Point graduates have begun to point out publicly—calls on them to be honest, direct and not evasive, and not to tolerate that behavior in others.

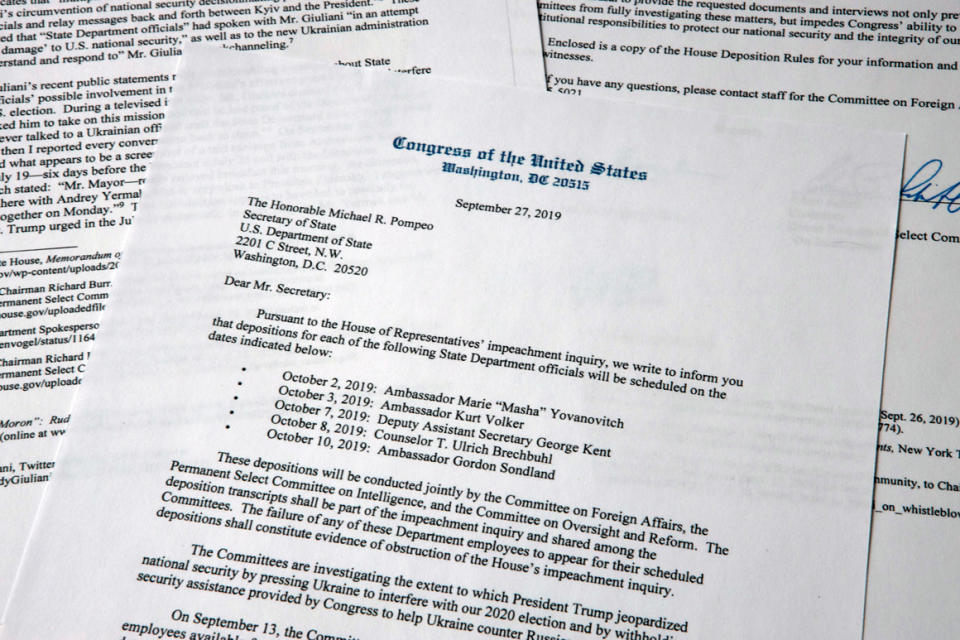

At least one of Trump's West Pointers has been subpoenaed in the House impeachment probe; Brechbuhl, who is the State Department’s counselor, has so far not met the House’s demand to appear. Impeachment investigators have demanded documents from Pompeo, who has defended the president’s actions as entirely appropriate and who has tried to resist efforts to get more State Department diplomats to testify. Other members of the elite group, including Esper, could soon also be compelled to testify about Trump’s alleged efforts, through his private lawyer, to hold up U.S. military aid to Ukraine in return for dirt on White House rival Joe Biden.

The group’s prominent place as defenders of the president and his policies is beginning to divide fellow West Pointers, some of whom watch what’s happening in Washington and worry their most prominent classmates are falling short of the code they all pledged to adhere to as cadets.

“Pompeo’s been caught lying, which horrifies me,” said Fred Wellman, a 1987 grad who retired as a lieutenant colonel and has been one of the more vocal detractors of his fellow cadets now running the government. “So I’ve been discouraged by what I’ve seen coming out of the military academy graduates involved in the administration.”

Wellman is among multiple West Point alums who have raised such doubts about their brethren, either privately or on social media. The academy’s honor code, which they are expected to uphold both in the Army and beyond, reads: "A cadet will not lie, cheat, steal, or tolerate those who do." It is the basis of the academy’s strict honor system, which doesn’t allow wiggle room in the definition of words like “lie”: “quibbling, evasive statements, or the use of technicalities to conceal guilt are not tolerated at West Point,” reads an Academy white paper about the system.

Other classmates, however, have stepped in to defend the group, insisting Pompeo, Esper and the others are more than equipped to honorably shoulder the burdens the unfolding firestorm has thrust on them—and that the country is lucky to have the class of ’86 at a moment like this.

“West Point taught us all a very strong value system, having a moral compass, doing the harder right versus the easier wrong,” said Joe DePinto, a fellow member of the class of ’86 who is now CEO of 7-Eleven and remains close to Pompeo and Esper. “I’m personally someone who sleeps better at night knowing that those guys are in the positions they’re in.”

***

Pompeo and his classmates arrived on the storied plain along New York's Hudson River in the first few days of July 1982, in the middle of President Ronald Reagan's first term, when the Cold War standoff with Soviet Union was at its height.

Pompeo has always been the informal leader of the former cadets. He graduated No. 1 in the class of ’86, a ranking that included cadet scores not just in the classroom but in the gym and on tactical exercises. “Pompeo was a very strong student—fastidious, deliberate,” recalled Doug Lute, a West Point social sciences professor who taught Pompeo and Esper and would go on to be a three-star general himself, overseeing the Iraq and Afghanistan wars on the Bush and Obama National Security Councils.

Pompeo and Bulatao, who is currently undersecretary of State for management, connected within hours of arriving at West Point in July 1982, Pompeo recalled in a brief interview. “You show up at Michie Stadium and the parents go one way and the kids go to a series of buses,” Pompeo said, “and you hop on a bus to go down to the training area for the first time and we ended up sitting on the bus together.” (Pompeo’s office at the State Department did not respond to a separate request to address the criticism from his fellow West Pointers.)

The duo was in the same cadet company as Brechbuhl, who was also a standout student. Brechbuhl and Urban, who was recruited to play football, were also both selected as part of the leadership of the class, known as the cadet brigade, during their senior, or “firstie,” year.

Like Pompeo, Brechbuhl was also an exceptional cadet, earning the designation of one of the “starmen” who got to wear gold stars on their collars. Esper wasn’t far behind, as the commander of one of the four cadet regiments and earning six merit stripes.

“Mark Esper was very mature as a cadet, all about standards and discipline when some of us were a little more like college students,” said a classmate who’s still in the military who did not want to be identified speaking about his boss. "He was what fellow cadets called a STRAC cadet: straight, tough, ready around the clock."

Esper and Urban traveled back and forth together between West Point and their hometowns in Western Pennsylvania on holidays and vacations. They also both later served in the 101st Airborne Division, where Urban helped introduce Esper to his future wife. They also served together in the 1991 Gulf War.

They weren’t all standouts at West Point, however. Urban was a “strapper” who had to attend the equivalent of summer school for failing both differential equations and mechanical engineering—thus forced to wear two stars inside his uniform jacket.

Green, in an interview, admitted he “struggled” and hadn’t been prepared for the academic rigor. “Quite honestly, I got my butt handed to me for three semesters and then I figured it out,” he said. “I think I made the dean’s list once.”

After graduating, most of the class were still on active duty in the Army when the Cold War ended in 1991—and many, including Pompeo, left active duty once their initial commitment was up and the U.S. armed forces were shrinking.

***

In the decades since West Point, the class of 1986 has stood out even by the standards of the hallowed Long Gray Line, as the generations of cadets molded into Army officers at the oldest of the military service academies are known.

Esper noted via email that “an exceptional share of graduates” have gone on to become generals, CEOs and leaders in the executive branch.

"I think we’ve got a dozen generals from the class," said Green, who was elected to the House last year.

Among them is Gen. Joe Martin, who is vice chief of staff of the Army, the service's second-highest-ranking officer. "Joey, we’re really proud of him," Green says, predicting "he’ll probably be chief of staff of the Army."

Other members of the class still on active duty include Lt. Gen. J.T. Thomson, the NATO land commander, headquartered in Turkey and Lt. Gen. Leopoldo Quintas, deputy commander of the Army’s Forces Command. Lt. Gen. Dan Hokanson heads the Army National Guard. Lt. Gen. Eric Wesley, deputy commander of Futures Command, is leading the Army’s efforts to modernize its equipment and strategy for the kind of great power conflict the Pentagon was expecting from the USSR in the mid-1980s, and has now reemerged in different form from Russia and China.

Indeed, the Russian threat still looms large over their discussions. “We talk about it a lot,” said Steve Cannon, who was a regimental cadet commander like Esper and later served alongside Pompeo in an armored cavalry regiment in West Germany in the waning days of the Cold War, says of the classmates’ private gatherings. “Now it is back to the future. You’ve got a fairly aggressive [Vladimir] Putin, who in many ways feels like he is pulling us back towards the Cold War. We do ruminate on those things.”

But it is out of uniform where the class has made its largest imprint. Green recalls that Army Gen. Mark Milley, the current chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, joked at a private event some years ago that the number of high-ranking civilian officials from the class of ’86 were giving the generals a run for their money.

“You’ve got a better shot of being a Cabinet member than being a four-star general in the class of '86,” Green recalled Milley as saying.

***

It is Urban who gets the most credit for orchestrating the class’ rise in Washington—and ultimately into Trump’s orbit. When Esper left the Army and was angling for a job on Capitol Hill, it was Urban, then working as chief of staff to Republican Sen. Arlen Specter, who recommended his classmate to work for then-Republican senator and future Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel. Urban also introduced Pompeo to key allies when he arrived in Congress in early 2011, including helping him land a perch on the Energy and Commerce Committee.

After Trump’s election in 2016, Urban’s role brokering top jobs for his classmates gained considerable altitude. Urban had first met Trump at a New York fundraiser for Specter, who died in 2012, but got to know Trump personally in 2016 working on the president’s campaign in Pennsylvania. “We clicked immediately. We hit it off. ... It was a time when nobody else thought Donald Trump stood a chance,” Urban recalled in an interview.

Urban put in a good word for Pompeo to be CIA director with Trump during the transition. He also advocated for Esper, first helping him become Trump’s Army secretary before he was tapped for the top Pentagon job earlier this year. At the past two Army-Navy football games, Trump visited Urban’s box, along with Pompeo and other members of the class.

Fellow classmate Steve Cannon, who is CEO of AMB Group, which owns the NFL’s Atlanta Falcons, and has hosted both Pompeo and Esper in Atlanta, sees Urban as the clear driver in the rise to prominence in Washington of his classmates —the man quietly steering events out of the public eye.

“He is a veritable force of nature,” Cannon said of Urban.

It was Cannon who enlisted Esper and other classmates in establishing the Johnny Mac Soldiers Fund, named for Col. John McHugh, who was killed in a suicide attack in 2010.

But nowhere are the class’ ties now more prominent than in Foggy Bottom. Pompeo, who credits the rise of the class to “just providence,” has had Brechbuhl and Bulatao at his side for years. The three first worked together at Thayer Aerospace, which Pompeo founded before he was elected to Congress from Kansas in the Tea Party wave of 2010. They also served under him when he was CIA director in Trump’s first year before following him to the State Department.

“Ulrich and Brian are literally my longest best friends in the whole world, and it’s an opportunity for us to serve together, which is really pretty special,” Pompeo told POLITICO.

The wider group also tries to get together regularly even with their busy schedules in Washington. To celebrate Urban's engagement last year, Pompeo and Esper attended an elegant party at the St. Regis Hotel organized by David McCormick, a member of the West Point class of 1987 and co-CEO of top hedge fund Bridgewater Associates, and now-wife Dina Powell McCormick, Trump’s former deputy national security adviser.

Other minireunions of the West Point Mafia take place monthly at eateries near the Pentagon such as the Lebanese Taverna, where one participant said they talk about “life stuff” and try hard not to get political. “Some I know from my earliest days at West Point,” Esper said via email. “Others I got to know here in Washington. Regardless, we all have common friends, experiences, and values from our earliest days at the academy.”

“We were a close class,” agreed DePinto, the 7-Eleven CEO who also served as a civilian aid to Esper when he was Army secretary. “We take care of each other. When one of us is down, we’re there to help. When some of us are successful, we’re all there to cheer each other on."

“I can always count on a West Point classmate when I have something that’s important to talk about or I’m in need of some sort of support,” DePinto added.

“Not every class is as tight and connected as we are,” Cannon said. “I will say that differentiates us.”

Esper describes a “unique level of trust and rapport” with Pompeo in particular, which he maintains “helps us both do our jobs more effectively.”

Each class at West Point designs its own coat of arms during its first year, and the motto emblazoned on the 1986 class crest is never far from the reach of Pompeo and Esper. Both men have “CNQ”—“Courage Never Quits—engraved on their official commemorative coins, which they’ve been known to hand out to subordinates as a token of appreciation.

***

How their behavior lives up to their cadet creed is being watched closely now by their fellow West Pointers as the hyperpartisan impeachment drama plays out. Esper waded into the controversy recently when he stood up for Army Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman, a senior staff member on the NSC, who oversees Ukraine policy and who has testified to House investigators in the probe.

Vindman’s integrity has been attacked by some of the president’s fiercest defenders, leading Esper to pledge that Vindman will not face any blowback in the ranks for coming forward. “He shouldn’t have any fear of retaliation,” Esper told reporters, adding that he has also relayed that message to the secretary of the Army.

Pompeo, however, has always hewed closely to the president’s line. That’s made him more of a lightning rod as he’s backed up the substance of Trump’s phone call with the president of Ukraine, while accusing House Democrats of bullying State Department officials into testifying. Inside his own department, there has been widespread anger that he has not backed up his own diplomats, including Marie Yovanovitch, the U.S. ambassador who was recalled early amid a smear campaign by Trump allies.

A retired senior Army officer singled out what he considers Pompeo’s double-speak about whether he was on the July 25 call between Trump and Ukraine’s president that is at the center of the impeachment probe. Pompeo initially gave the impression he did not participate before admitting he listened in on the controversial call.

“It’s been very disappointing to see it, because it goes in the face of everything we were taught at the academy,” said the retired officer, who asked not to be identified to speak freely. “It’s dispiriting to see how easy it is to quibble when it’s convenient. That’s a West Point word, used to mean dissemble,” or tell half-truths, the officer said, noting that he’s seen “a lot of talk” among fellow graduates on social media about Pompeo’s handling of the Ukraine affair.

“It’s not just that he’s a West Point grad,” he added. “It’s that it’s part of his brand and he brings it out all the time.”

Eliana Johnson contributed to this report.

CORRECTION: Ulrich Brechbuhl’s title was misstated in an earlier version of this article.